One of the passages in my book I’m most proud of is the one in which I analyze my transcriptions of Ives’s recorded performances of the Four Transcriptions from Emerson (passages of the Concord‘s Emerson movement that he revised to be closer to the way he played them). One of my external readers advised firmly that this chapter should be stricken from the book. That’s right: for the first time, someone transcribed what actual notes Charles Ives played when he considered that he was playing Emerson, giving us a chance to see how what Ives thought with his fingers differed from what he wrote in the score, and a distinguished (one presumes) music professor declares that this has no place in a book on the Concord Sonata! It didn’t teach him anything about the Emerson movement, he says; but might it teach us something about Ives? Isn’t peer review grand?!

I have taken advantage of the blog format to do something I can’t do in a book: provide audio files of the recordings I transcribed, which I managed to embed in the blog page. They work on my browser, and I hope they work on yours.

**************************

From Chapter 6: The Emerson Concerto and its Offshoots

On four occasions in the 1930s and ‘40s Charles Ives went into a recording studio and had someone record him playing the piano:

* Columbia Graphophone Co., 3 Abbey Road, London, June 12, 1933 – shellac pressings

* Somewhere in NYC on an unknown date in the mid-1930s (between 1934 and 1937) – Speak-O-Phone discs on aluminum

* Melotone Recording Co., NYC, on May 11, 1938 – lacquer-coated blanks

* Mary Howard Studio, NYC, on April 24, 1943 – lacquer-coated blanks

He recorded some 42 tracks, some interrupted and picked up where they left off because the recording media of the day would not accommodate more than five minutes to a side. Three of the 1943 tracks were excerpts from the Emerson movement, seven and a half minutes in total1; in 1938 he tried to play Hawthorne and quickly broke off; and in 1943 he managed to play The Alcotts warmly and in its entirety, a precious document we will have occasion to study. Fifteen of the tracks, including some of the most complete, were of a relatively new piece called Four Transcriptions from Emerson, which consisted of sections from the Emerson movement as rewritten in the 1920s; they are attempts to play the movement more the way he liked playing it himself than was represented in the sonata’s 1920 publication, and the first in particular has passages from the original Emerson Concerto written back into it. He also played some of his Studies for piano, including portions of Nos. 2, 9 (subtitled The Anti-Abolitionist Riots of the 1830s and 1840s), 11, 20, 23 – all of these except No. 20 were written from material in the Emerson Concerto.

Thus, of the 42 tracks Ives recorded across these four occasions, no fewer than 31 were of material related to Emerson from the Concord Sonata. Ives was clearly intent on getting across his idea of Emerson with his own hands. He was only 58 at the first recording session, 68 at the final one, but though the recordings let his impressive prowess at the keyboard shine through at moments, he sounds like a rather frail old man. Diabetes at its worst had once reduced his weight to a hundred pounds, vitiated his eyesight, led to heart palpitations, and caused crippling neuritis in both arms, and though his weight and health began improving after the initiation of insulin treatments in April of 1930, his weakness is evident in his fumbling and at times arrhythmic interpretations. [All this information is footnoted to Budiansky’s Mad Music elsewhere in the text.] He often breaks off playing, muttering, “Oh, no, I can’t,” or ”Oh, I have to stop,” or ”That’s enough.” He also hums or sings or groans at moments, and the most touching entry is the song “They Are There†with Ives singing lustily but erratically as he accompanies himself, made in three takes in 1943 – he apparently hoped the song might gain some currency in the wave of World War II patriotism. Also, one item I find psychologically gratifying is that in 1938 he suddenly played a couple of minutes of the first-version Largo for his First Symphony that Horatio Parker had rejected and made him rewrite because it went through too many keys. Forty years later, he still had that music in his head, and he was not going to let Parker have the last word.

The sound quality, coming from soft aluminum or lacquer-coated discs, is highly variable, but for a 2000 compact disc release on CRI records, Richard Warren Jr., the curator for historical recordings at Yale University, transferred the original discs to digital sound files using a Packburn Audio Noise Suppressor, and repairing needle jumps via computer. Following CRI’s much-lamented 2003 demise, New World Records reissued the recording in 2006. Some of the tracks had already appeared on a Columbia vinyl recording during the Ives centennial. Mary Howard, the recording engineer for the 1943 session, remembers Ives saying that certain people had asked questions about how to interpret his music, and added, “Interpret! Interpret! What are they talking about? If they don’t know anything about music – well, all right, I’ll tell them.†“[H]e’d pound and pound,†Howard recalled, “and Mrs. Ives would say, ‘Now, please take a rest.’ He drank quantities of iced tea, and he’d calm down and then go back at it again, saying, ‘I’ve got to make them understand.’†And it helped. As we’ll see, these recordings have provided considerable insight toward restoring that mythical behemoth the Emerson Concerto…..

[Here follow sections on the Emerson Concerto as realized by David Porter, the related Piano Studies, and the Four Transcriptions from Emerson.]

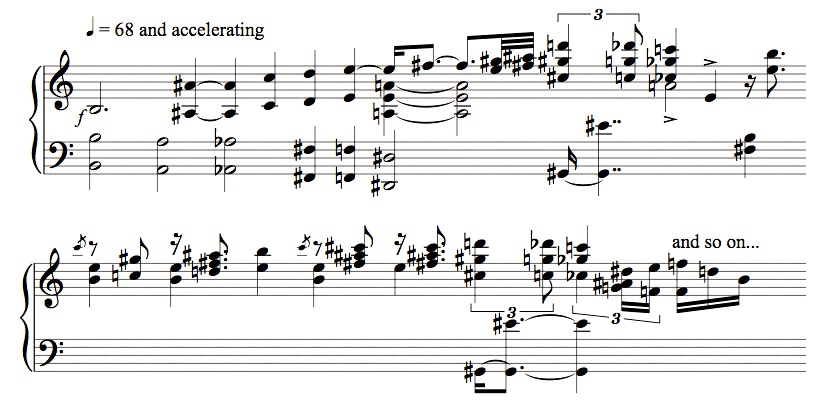

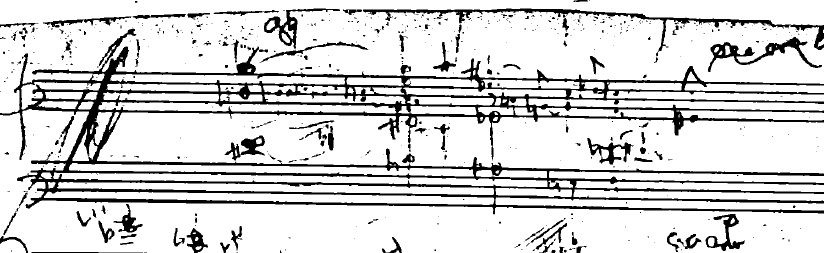

Ives’s 1933 recording of the First Transcription (though he does not limit himself to that score) is one of the best documents we have tracking his thinking about the Emerson Concerto. He more or less plays the first two measures of the Transcription (corresponding to the first system of the Concord, and mm. 3-4 of the Concerto), and then skips to m. 14 of the Concerto (corresponding to page 2 of Study No. 9, for a long passage absent from the Transcription), rejoins the Transcription toward the end of Study 9 and then follows it into the Study No. 1 material, proceeding into Study No. 2 and following it to then end. In short, he basically plays the first 87 mm. of the Emerson Concerto except for mm. 1-2 and 5-13. This is as close as we can get to hearing Ives play the Emerson Concerto himself, as he had it in his hands and head, including the first three centrifugal cadenzas. He left us a compelling record that this really was the way he wanted it. Except, he has a moment of seeming uncertainty at the beginning, going into a little repetitive riff on a few chords before rebeginning the descent, something as in Ex. 6.9.

Ex. 6.9 Emerson Transcription No. 1 opening, as played by Ives in 1933

One has to wonder, at such puzzling moments in the recordings, whether he was intentionally improvising, or had a moment of indecision or misremembering about what to play next.

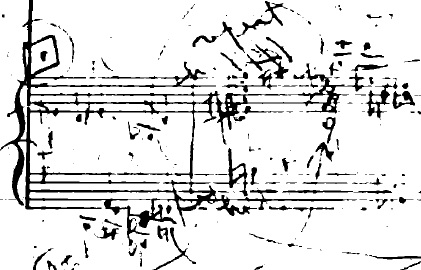

Thus the First Transcription. Our primary reason for spending time with the Third Transcription is that Ives interestingly (and clearly intentionally) deviated from the score every time he recorded it. As (soon to be) printed, it follows the sonata movement fairly literally, with almost unnoticeable note changes, from sys. 14-3, m. 3, through the first six beats of sys. 16-4, at which it dies out with a repeated C and a few pppp dissonant chords. How Ives played the movement at his four recording sessions, however, was different indeed. The first measure (corresponding to sys. 14-3, m. 3 in the sonata), he never plays literally at all. In each case he played a rather rambling introduction which eventually leads into the second movement of the printed Transcription. In my own transcription of these four introductions as recorded, we can get a view of Ives as improviser over a ten-year period.

A word about the following (and preceding) transcriptions: I do not vouch for the notes in detail. The sound quality of these recordings is not at all pristine. I have played the audio files at different speeds in an attempt to get all the notes, and in so doing, a note that seems audible at one speed will disappear at another; a note sustained from a chord may sound like it has been restruck when it hasn’t; dissonances deep in the bass may be mistaken for tremolos and vice versa. I have even made use of pitch-transcription software, which, because it will sometimes register harmonics of notes as well as the fundamental, I have found generally inferior to my own ears. The rhythms are more secure, since one can pinpoint in the audio file the exact time-point at which a note starts, and Ives does maintain a fairly clear feeling of beat. I think my transcriptions are adequate for showing the variations in Ives’s improvised versions of various passages, and I think they are followable with the recordings, but I am sure that close listeners to the recordings will disagree with some of my note choices, as I have so many times come to disagree, upon further listenings, with my own.

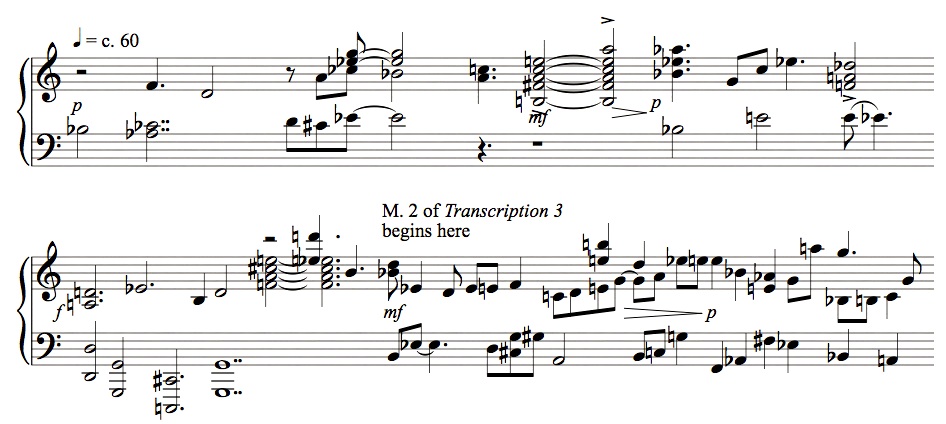

Subject, then, to the limitations of converting audio to notation, Ex. 6.10 shows what Ives played to open the Third Transcription in 1933. [The third Emerson transcription starts abruptly with page 14, system 3, measure 3 of the Concord. Admittedly, the scores of Ives’s Transcriptions are in the process of being published and not available yet.]

Ex. 6.10 Beginning of Third Transcription as played by Ives in 1933

Note the opening on a Bb; the move to a diminished seventh chord; the momentary cadence on Eb-major; the rise to A and then Ab; the C-minor triad in the right hand contradicted by the E-natural in the left; chromatic rumblings in the bass around D, C#, and Eb; and then the Transcription pretty much takes off with its second measure. A couple of years later, Ives records the piece again, and we find all these elements preserved, though with some differences (Ex. 6.11).

Ex. 6.11 Beginning of Third Transcription as played by Ives in mid-1930s, take 1

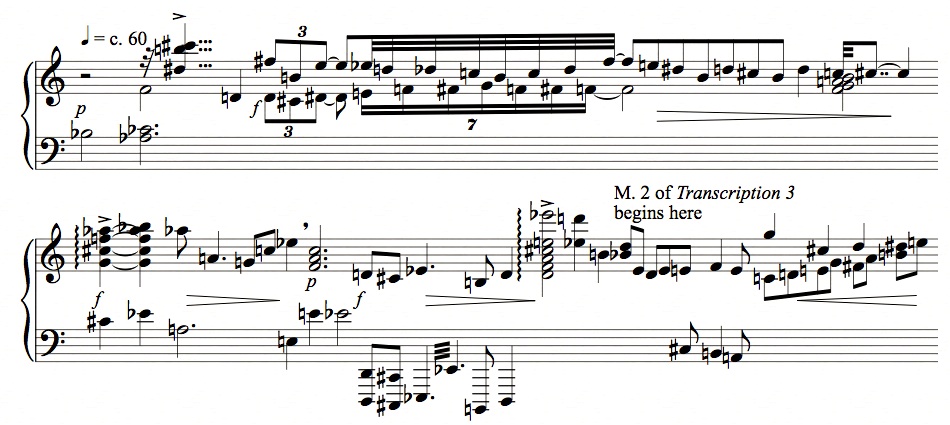

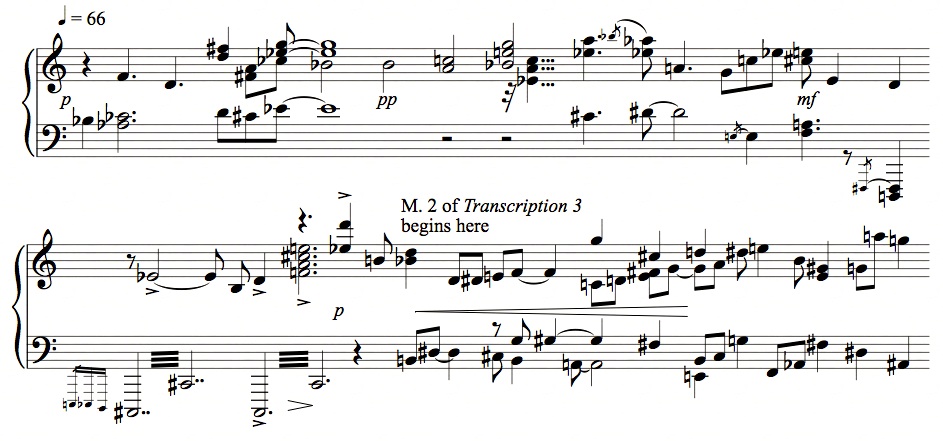

In 1938 Ives makes a third recording, and all the elements we’ve named are still intact except for the cadence on Eb, which is replaced with a flurry of chromaticism and a recitative-like solo line (Ex. 6.12).

Ex. 6.12 Beginning of Third Transcription as played by Ives in 1938

In 1943 Ives makes his final recording. Here (Ex. 6.13) the opening Bb proceeding to a dminished seventh chord is jettisoned, replaced with a more dramatic flourish leading directly to the treble Ab and also dispensing with the Eb-D treble sonority which, in the other three versions, led into the notated part of the Third Transcription.

Ex. 6.13 Beginning of Third Transcription as played by Ives in 1943

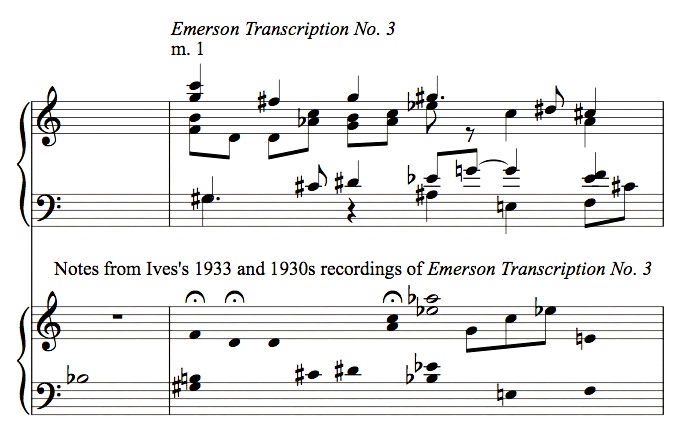

These four versions of an improvised introduction to the Third Transcription contain enough similarities to demonstrate that Ives had in his head (and fingers) a number of elements which, for him, constituted the opening to this work. Such recurring elements as reappear always occur in the same order. Porter found some of these elements in two sketches on pages associated with the Emerson Transcriptions. At f4890 (Ex. 6.14) we can see the Eb triad (though with a D# and B-natural), some notes moving to the A-C dyad, the chord with G on top going to A and G#, the G-C-Eb motive with E-natural in the bass, and the F-major triad with an E descending to D#.

Ex. 6.14 Notes from Third Transcription at f4890

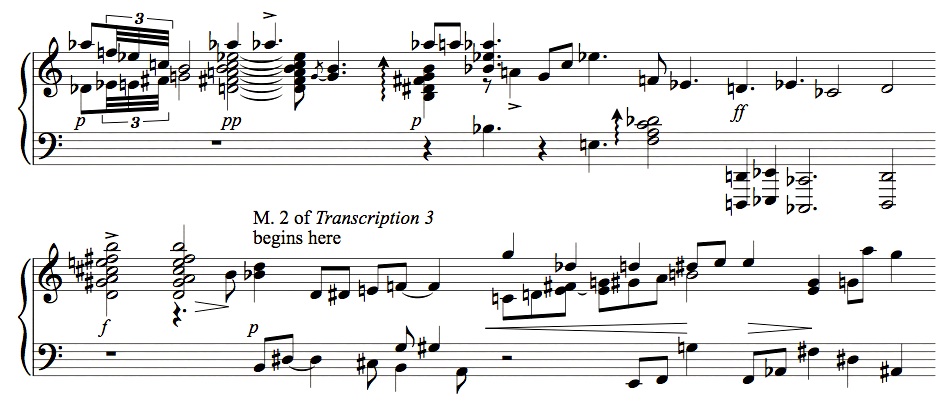

At the end one will notice a D in the bass, and at f4947 – a printed page of the Third Transcription with many emendations by Ives (Ex. 6.15) – we find the Eb-B-D motive (Ives’s naturals can sometimes look almost indistinguishable from flats), and it precedes the B-D#-F#-A-C-E-G chord we’ve already seen.

Ex. 6.15 Notes from Third Transcription at f4947

If we compare the notes Ives played in his first recordings with those in the score of the Third Transcription and Sonata movement, we see some correspondences that would be difficult to notice, since the fugal theme on top is omitted and some of the notes are sustained at much greater length (Ex. 6.16).

Ex. 6.16 Correspondence of Ives’s improvisations to the notated Third Transcription

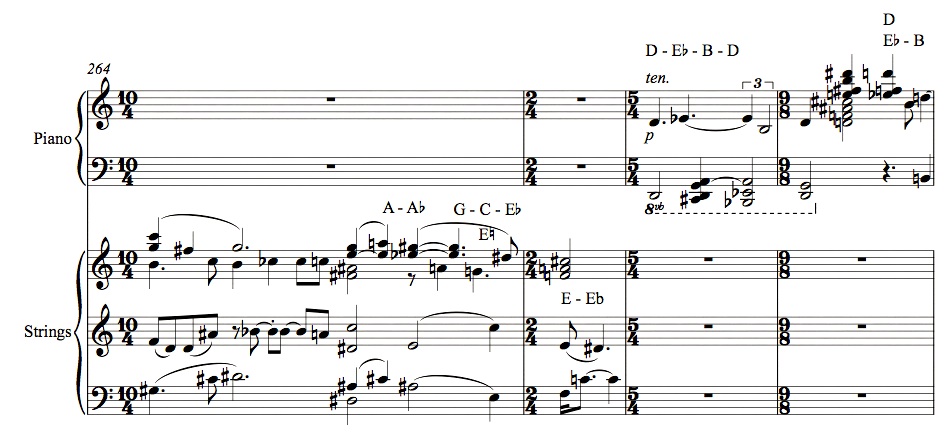

Thus, for the correlating passage of the Emerson Concerto, Porter combined the Third Transcription (identical to the Sonata movement in this case) with some of the elements found at f4890 and f4749 and, using Ives’s 1933 recording as a guide, worked a corresponding two-measure piano intrusion into this point (Ex. 6.17).

Ex. 6.17 Emerson Concerto, mm. 264-267

In later years, as we can notice above, Ives began treating the Third Transcription’s opening a little more rhapsodically. Nor does he follow the printed score closely once he reaches m. 2 of the score. In particular he tends to replace the first nine beats of sys. 14-5 (in the sonata) with a group of repeated chords and then some repeating motives or chromatically moving chords, before restarting with the syncopation in the notated tenth beat. The point of the recording for Ives, one gathers, was to introduce the quick runs that were eventually notated on page 15, so he tends to play that passage fairly literally. Each version except the 1943 (which he abandoned in mid-take) does die away with a repeated note (or minor-ninth dyad) and chords, but the number of repetitions vary, as do the chords. These variations suggest what has been speculated28, which is that Ives was probably making the recordings from memory, without a score in front of him. The loud Eb-B-D motive with the bass octaves or tremolos is related to a minor-2nd/minor-3rd motive, but there seems to be no hint of the fugal theme in the introduction, nor of any of the other Emerson themes. Ives didn’t write this material down as part of the Third Transcription, but he carried it around in his head and could reproduce it fairly similarly, if evolvingly, at intervals of several years each. This gives us as close a picture as we can get of how he would improvise on and expand a piece that he thought of as relatively fixed in its material.

From the comparison of these transcribed recordings with the printed Third Transcription from Emerson and the sketches, I think we learn something both about Ives’s improvisation style and his playing in general. It seems from the available evidence that when he played rather extemporaneously Ives tended to have in mind a musical structure that he had already worked out. His idea of timing and tempo was extremely flexible, and here we find him holding out at great length notes that he had written as a series of eighth-notes in the final score. He seems not to be just “making notes up,†but recomposing, as he plays, a passage that had for him some kind of firm identity in its relationships, though he felt free to interpolate motives and chords within it. He will write next to a sketch, “I find I play something like this here†(as Porter found on f2230)29, or write “sometimes†next to an accidental. This is not free improvisation, but reconsidering over and over how a passage might have been written. One thinks of the complaint of Ives’s grandmother who, hearing Emerson lecture, found that “the printed text, which she knew almost by heart, was hardly more than an outline in his lecture. Apparently Emerson liked to trust to the mood of the moment….†One could hear some of these recordings and think of Ives’s printed scores as merely outlines. “Music may resent going down on paper!,†Ives wrote to Cowell.30 The classical musician’s inability to identify with that jazz attitude has been the source of misunderstandings about Ives.

1 The passages of Emerson Ives played in 1943 included system 5-3, beat 10, through p. 6; sys. 17-1 through 18-1, m. 1; and sys. 14-2, beat 4, through 18-1, m. 1.

2 Budiansky, Mad Music, pp. 1, 207, 213.

3 Vivian Perlis, Charles Ives Remembered: An Oral History, p. 210.

……..

28 By, for instance, James Sinclair in the liner notes to Ives Plays Ives, New World Records 80642-2, p. 6.

29 Porter, p. 17.

30 Ives to Henry Cowell, August 12, 1928; quoted in Owen, Selected Correspondence, p. 155.

All material copyright © Kyle Gann 2014