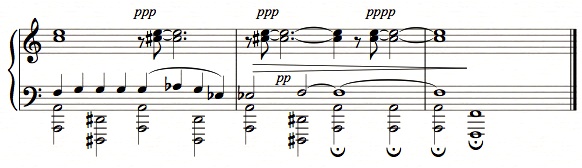

Here are the last three measures of the Concord Sonata‘s Emerson movement, as published in the score he sent out in 1921, which is now in public domain, and which – ill advisedly, in my view – has just been reprinted by Dover:

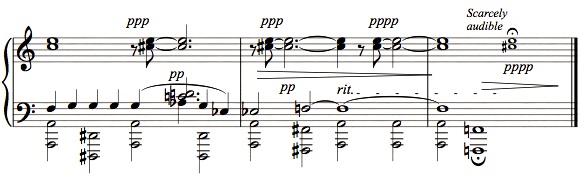

And here are those last three measures in the second edition of 1947:

There are several changes here – the addition of the C-D cluster, the reiteration of the final treble dyad, the replacement of fermatas with what seems a more judicious ritard – but the one that interests me most is the replacement of the final D# with F# in the bass line. By setting up an F#-A dyad in the listener’s ear, it renders the final F (which, of course, is the close of an intentional Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony motive) a touch more surprising. The A, D#, and F could be heard as belonging to the same harmony, but the A, F#, and F cannot – in addition to which, in conjunction with the tenor melody, the final D# came precariously close to rooting the tonality in Eb (D#), lessening the delicious ambiguity, and making the final F sound like a second scale degree rather than a new, unexpected tonic. It’s a small change, but a poetic one and perfectly right. In addition, the F-E-C# at the end (with the added harmonics) expresses a 1-3 pitch motive (minor second-minor third) that is important earlier in the movement, being first heard starting from the left hand’s second note. This pitch set is now found in the closing bass pitches F#-A-F as well.

If it matters to anyone, the change from D# to F# is not included in the Four Transcriptions from Emerson, which, based on Emerson, was completed and copied in 1926, which suggests that Ives must have made the change after that date.

Aside from the better-known big dissonant parts added to Emerson, there are dozens of such improvements that Ives made to the 1920 score in the 1947, things that hadn’t been quite right yet, that were surprising and original but not yet magical. I’m detailing many of them in my book. Thus I think it’s rather a shame that Dover has issued a cheap reprint of the 1920 score, which is deficient in many, many respects. Its reappearance in the popular Dover series will convince many buyers that they are getting the real Concord Sonata – and though not everyone agrees with me, I believe it does this great work a disservice.

(Of course, I am sufficiently inured to the internet to know that since I expressed a preference, I’ll now get plenty of comments saying they like the 1920 version better, just as when I produced a clean recording of a Harold Budd piece, there was no end of people saying they preferred the one with the baby crying in the background. If I blogged that I preferred my wife’s cooking to roadkill, the defenders of roadkill would form a line. Such comments will be taken seriously if the writer can explain his reasoning in as much logical detail as I have above.)