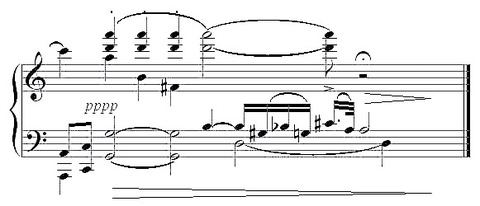

NEW HAVEN – I played the last two movements of the Concord Sonata in high school, and the final four articulated notes of “Thoreau” – G# Bb G C# – have always bothered me. I remember arguing with my piano teacher about them. They don’t seem to have much motivic resonance with the rest of the movement, and the final ambiguous tritone always struck me as un-Ivesian. So now I’m at Yale library looking through the Ives archive, and I’m finding that Ives’s original manuscript presented a different picture. The original ending, which was followed in the 1920 edition but was dropped for the Arrow Press Edition, followed that C# with a dotted-rhythmed A:

This makes perfect sense, and connects the ending with several other points in the piece:

It also brings back at the final moment the wedge motive – notes moving outward or inward chromatically around a center note – that recurs many times, notably in the opening measures, and also closes the piece on a more conclusive-seeming D-A sonority. (In one sketch, Ives even suggests that the last six notes could be played an octave higher by, not the piano, but the flute that barges in on the preceding page.) And yet in the 15 copies of the published version that Ives went through and altered to create several possible readings of the piece, he several times crossed out the A and made the C# a half-note. I think doing so was a mistake, and not the only one Ives made in belatedly revising his works. (I also never liked the 12-tone chord that he puts at the end to make fun of his Second Symphony.)Â

Likewise, I’ve always wondered about the beginning. The first five notes of the Concord in the left hand descend B A Ab F D#. Everyone analyzes this as a skewed version of the “pentatonic theme” that will recur so often, E D C A G. But it’s not pentatonic! And lo and behold in the first ink copy of the piece, the left hand descended B A Ab F# F D#, with two quarter notes:

It’s octatonic! And with a whole-tone scale in the right hand and octatonic in the left, perhaps he was spelling out a larger-scale wedge motive. But he crossed out the second quarter-note and put a half-note. The realization that his original idea was not thematic but scalar gives me something new to look for in the piece.Â

I’m considering teaching a Concord Sonata course next spring, and I’ve always suspected that if I could look at the sketches I could clear up, at least in my own mind, some mysteries about how Ives composed. And I’m grateful to the librarians here for allowing me to gaze my fill at these precious manuscripts.Â