Your generous responses to my little outburst about being tired of blogging certainly made it clear what most useful direction this blog can continue to go in. I may be out of ideas I haven’t expounded, but my file cabinets and hard drives are still chockablock with music that’s not in general circulation, and listeners are eager to have their experience widened. If I do no more than satisfy that longing, I will have felt that my trip to this planet was not in vain. If I become in the process sort of the Dick Cavett of avant-garde music, so be it.

One of the themes of my life has become something I never expected. I’ve based some large part of my career around documenting recent music not adequately represented by its score notation. It started with Nancarrow. His scores contain all of his notes, of course, but many of them, especially the late player piano studies, don’t provide as much explicit rhythmic notation as is actually inherent. After some brief acquaintance with Nancarrow’s music I formed a theory that, even when it looked like he was rather intuitively splashing notes onto the page, there was always some underlying tempo and even isorhythm to which everything referred. Some painstaking analysis with a little plastic millimeter ruler quickly bore me out, and I found further confirmation when I was able to consult his punching scores – from which he made his final scores, but omitted the messy tempo-grid information.

Since then I have stumbled upon a wealth of music whose score notation, if it exists at all, doesn’t adequately represent it. I reconstructed Dennis Johnson’s November from the recording and score fragments, and have spent time transcribing improvisations by Harold Budd, Elodie Lauten, and others. I’ve reconstructed some of Mikel Rouse’s ensemble music from parts and mathematical models. Harry Partch’s music is indecipherable as to pitch unless you know the various tablatures of his instruments, and, in the case of his Kitharas, I’m told that you can’t figure out the music without knowing how to play the instrument.

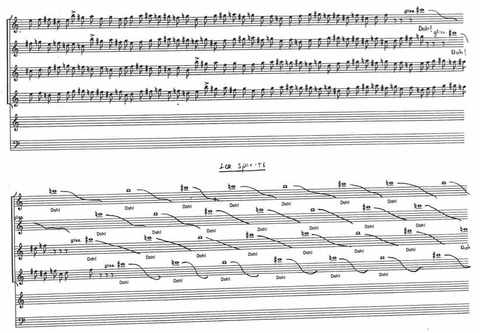

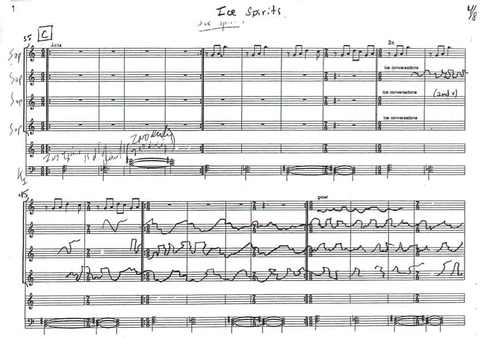

Lately I’ve finally been studying a rather sketchy 392-page score to Meredith Monk’s 1991 opera Atlas that she was kind enough to give me years ago. Meredith refuses to have her singers learn music from notation because it detracts from a lively performance; she prefers to sing their lines and have them sing them back, as in Indian music. The Atlas score pretty much contains the instrumental parts verbatim, but some of the vocal parts are left blank on the page, indicating that they were to be developed in rehearsal. Scores to two of the most beautiful sections, “Choosing Companions” and “Agricultural Community,” contain no vocal parts at all. The “Ice Demons” music, when compared with the recording, shows how precise some of her notation is, how free it is in other places, and how free the singers were to ignore it in either case:

The whole score is a fascinating document of Meredith’s working method. Occasional passages are blanked out, omitted in rehearsal, and where the vocal rhythms (heard here) are exactly notated, the actual performance is often much freer:

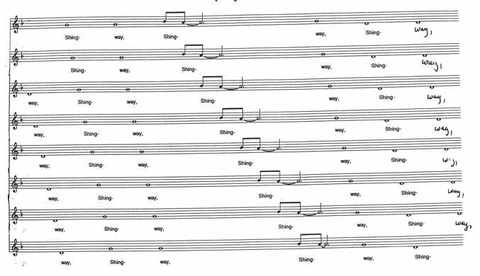

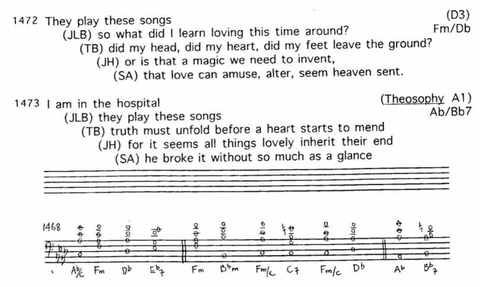

It’s difficult to imagine improving on the unconventional notation of the “Shing Way” section, in which the singers sit in a circle and pass each pitch or figure linearly from one to another (recording here):

I don’t know whether, since 1991, Meredith has made a nicer, more complete score of Atlas, but why should she? This was adequate for a series of stunning performances, and it represents a starting point for the piece, not an end product in itself. Some musicologist could certainly prepare a nice final score using this and the recording as guides, but this one tells more about Meredith’s working method than an engraved Universal Urtext ever could.

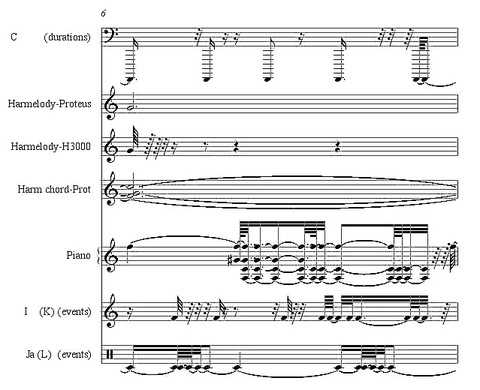

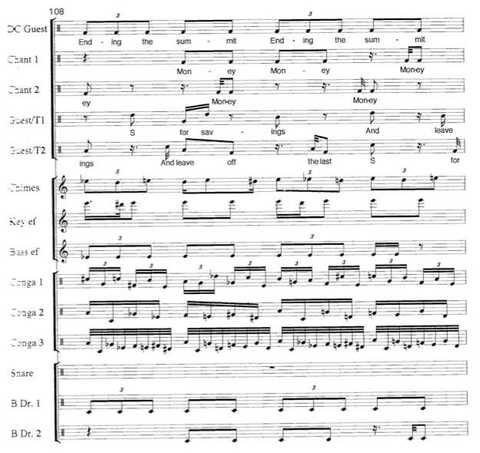

The lack of scores is a big issue for studying Robert Ashley’s music as well; or rather, the discrepancy between his spare working scores, his “production notebooks” as he calls them, and the information overload on the recordings. Years ago when I analyzed Improvement: Don Leaves Linda with a class, Bob kindly gave me the complete MIDI files for the piece, but correctly warned me that they wouldn’t be much help. They were used to trigger events in primitve 1980s software that no current computer still supports, and it’s only here and there that one finds telling correspondences between the MIDI and the recording. Translated to notation, the MIDI files look something like this:

It’s possible that some tracks triggered only markers heard by the performers through headphones, and not by the audience.

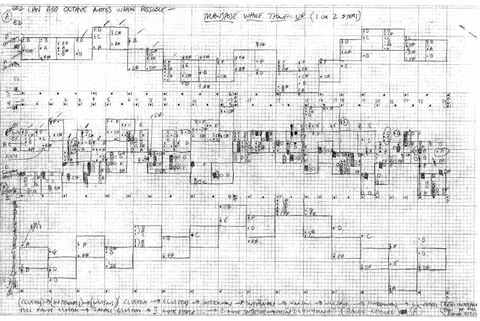

More typically, Ashley’s actual scores contain the libretto marked out in numbered lines, surrounded by harmonic or melodic notations where needed, like this page from Dust:

Ashley takes on the problem of how someone else could perform his operas in an article called “Style and Technique: Performance Practice,” which is collected with his other writings in a dazzlingly huge and mind-challenging new collection of his writings from MusikTexte titled Outside of Time: Ideas about Music, which I will surely be writing more about later. “The solution,” he writes,

is to get all of the operas recorded in a finished form in the most recent format (now, compact discs). Anybody who wanted to produce one of the operas could work from the compact disc, which represents the way the opera is to be performed and how it is supposed to sound. Except for the rhythmic treatment of the words, which remains a notated constant, there is no score from which to make the orchestra. As I have said, the studio production notes for any opera will make little sense in the future, even if I could decipher them now, because they refer to instruments that will be long gone.Â

He talks about a student writing a dissertation on Perfect Lives, to whom he had to explain that a score did not exist.