As my co-director David McIntire so aptly said in his opening remarks to the Second International Conference on Minimalist Music, minimalist music has always stressed community – not only in its unison-rhythmed, non-soloistic ensemble style, nor in its tendency to bring an audience together in a kind of mass ecstasy, but in the collective enthusiasm it kindles among its devotees. This was evident in the first conference in 2007, and became even more apparent last week in Kansas City. That group of us who attended both conferences – myself, David, Keith Potter, John Pymm, Pwyll ap Sion, Maarten Bierens, Tim Johnson – developed a deeper sense of camaraderie and common purpose. Those who regretted missing the first conference and loved this one filled us out into a larger circle. The excitement that followed Sarah Cahill’s fabulous recital, Charlemagne Palestine’s transcendent organ performance, and some of the more thought-provoking papers quickly communicated itself from person to person. Everyone seemed in an excellent mood all week, and in a more ebullient mood from day to day. The best minimalist music does not inspire cautious appraisal or cold analysis, but wide-eyed wonder. Those of us who love it found ourselves at home in Kansas City, and among kindred spirits.

I shouldn’t go too far in complimenting elements of a conference I helped plan, but I will make a few evaluative comments that hopefully won’t reflect on myself. Sarah’s elegantly flowing performance of Harold Budd’s Children on the Hill proved to my satisfaction that a transcription of the piece can be played in a spirit virtually indistinguishable from Budd’s own. I’ll post the recording as soon as I get it. She also reminded me of what a gorgeous piece Meredith Monk’s St. Petersburg Waltz is, and she introduced quite a few participants who hadn’t heard of it to Hans Otte’s scintillating The Book of Sounds, creating quite a stir for the piece.

No quantity of listening to Charlemagne Palestine CDs could have prepared one for the mammoth presence of his organ performance Schlingen-Blängen, a piece he first played in 1965 but had never played in the U.S. before outside Los Angeles. (In fact he’d never visited the Midwest before.) As we entered Grace and Holy Trinity Cathedral, a perfect fifth was already ringing on the organ. Little by little Charlemagne added notes, held down with little wooden splints, and pulled out additional organ stops to thicken the roar of sound. Finally he plunged onto the keyboard with both forearms, and, with overtones at maximum ferment – pulled the plug. The sound died in a swooping glissando, came back on, and did so twice more, in a powerfully dramatic effect. There was an audible bass line running through much of the piece, and after the organ finally died away for the last time, Charlemagne rang a drone on the rim of a cognac glass and sang the bass line in falsetto – it was the final ostinato melody from Stravinsky’s Firebird, not recognizable as such in the melee of drones. Here are Scott Unrein’s photos of the church as it looked to us, with the organ in the background and Tom Johnson’s ghost arising from the time exposure:

and Scott’s portrait of Charlemagne in action:

Despite his recent book on Terry Riley’s In C, Robert Carl’s own music is not noticeably postminimalist, and so he may have seemed like an odd choice for keynote speaker, but he was pitch-perfect. He first dismissed the facile platitude that minimalism might have been nature’s way of clearing the decks from serialism and making it possible to return to the relative “normalcy” of orchestral music like that of John Adams; instead, he said (and I’m paraphrasing from memory after a hectic teaching week), the radicalness of early minimalism was no mere aberration but a continuing and essential feature of the style. He then went on, as only an outsider to the movement could have, to detail what he thought minimalism had contributed to early 21st-century music in terms of flow and transparency. It was a moving tribute, and I told Robert afterward how much better he does public sincerity than I do.

As I’ve said, I had hoped that the conference would bring about some potent distinctions between minimalism and postminimalism. Galen Brown’s brilliant paper “Process as Means and End in Minimalist and Postminimalist Music” achieved a climax in that respect, widely noted as such. For Galen, minimalist music cared about process as a means regardless of what the sonic result was; postminimalist music uses process only to the extent that it achieves the sound the composer hears in his head. It was an admirably clear formulation, and I haven’t yet found a loophole in it. That paper, along with two others by Kevin Lewis and Andy Bliss, provided a remarkably rounded view of David Lang’s aesthetic, showing how willing he is to derive materials from processes that the listener can’t necessarily hear, yet disrupts his own processes sporadically to make his music more human. Scott Unrein drew out the sensitive subjectivity in Jim Fox’s music, and introduced that name to many present.

I’m disappointed that we didn’t get any of composer Paul Epstein’s music on the concerts, but his paper gave an absorbing account of the compositional structures he’s derived in the technique called “interleaving” that he took from Reich’s Piano Phase, which he’s developed into a surprisingly wide-ranging postminimalist technique. A paraphrase of his paper could make an entire chapter in this Music After Minimalism book I’m allegedly working on. Sumanth Gopinath and Gretchen Horlacher offered analyses of, respectively, Reich’s Different Trains and Tehillim that made me realize that my listening to Reich has become one-dimensional, as though I only hear what I’ve already come to expect. Sumanth in particular drew resemblances to tropes from various popular musics, and made me hear the music anew.

As for Dennis Johnson’s November, which Sarah and I gave the world re-premiere of, our rendition took four and a half hours, switching pianists every hour. The experience showed me a few things I still want to refine in my version of the piece. Luckily Sarah got the more melodic sections and made them heavenly. I realized that my own rusty piano technique was barely adequate even at November‘s leisurely tempo, but afterward Neely Bruce – a dynamite pianist himself – described my playing to me in detail in a way that made me feel good about it. I certainly loved doing it, and it’s the first time since the mid-1980s that I’ve performed, in a professional setting, anyone’s music except my own. Several conference participants had to leave to catch planes during the interim, but the 19 who managed to hang on to the end gave us a standing ovation, which in my case I took more as a compliment to my hard work and endurance than to my pianism. (Photo by Robert Carl)

I got home Tuesday at 1 AM and faced an eager Renaissance counterpoint class nine hours later. My luggage followed on Wednesday afternoon.

Per our group deliberations, the Third International Conference on Minimalist Music will take place – [drum roll, please] – in mid-October of 2011 at the University of Leuven in Belgium, a medieval university town 15 minutes from Brussels by train, under the leadership of Maarten Bierens. I already can’t wait. There was copious discussion of what institution in the U.S. might pick up the Fourth conference in 2013, but the story in every case was the same: at each representative’s school we considered, the musicology faculty would welcome the opportunity, but the resident composition professors would shout it down. That UMKC showed us such hospitality has made it one of the handful of schools I now recommend my student composers to consider for graduate studies. Musicology is the field through which minimalism is making its way into academia, and it is remarkable how many young minimalist-oriented composers, several of them in attendance in Kansas City, are getting their degrees in musicology as a way of bypassing the hidebound stodginess of the academic composing world. This conference is a confederacy of (mostly) young composers and musicologists allied to break the grip of modernism’s stranglehold on American academic composition departments. Our success in that venture is only a matter of time. God bless the musicologists for their exuberantly erudite support.

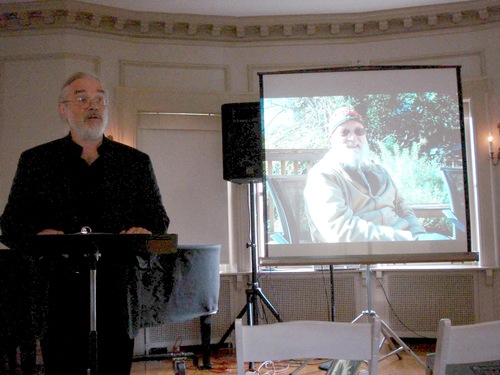

UPDATE: Pardon me, but I like this photo of me, by Robert Carl, explaining November: