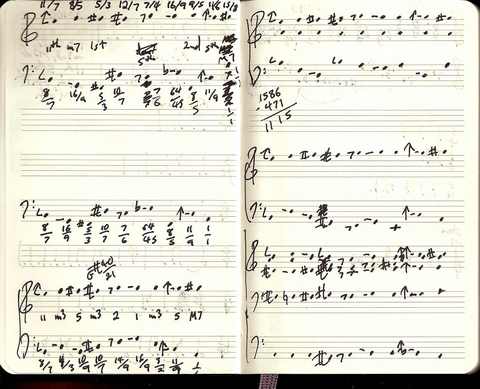

If you have a friend who’s considering becoming a microtonal composer, and you are frantic to spare him a life of agony and unfulfillment, I’m about to do you a big service: just have him read this. All day yesterday and this morning I spent hours filling my little sketch book with pages of notes and numbers like this:

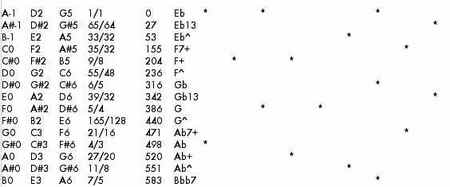

I was looking for a series of fractions between about 1.5 and 1.9, and then trying out different ways of harmonizing them so that 1. you don’t get any parallel chords close together in the series, 2. the same chord roots don’t get repeated, 3. a variety of different kinds of 7th chords are available, and 4. the harmonies use the smallest-number fractions conveniently available. I think of it as kind of like a four-dimensional sudoku puzzle. Yesterday I ended up with the scale from complexity hell, that was going to require maybe 80-something different pitches. This morning I woke up with all these numbers in my mind, along with a sound: and that sound gave me the key to simplifying the principle of the scale. So I jumped out of bed and compiled a new, far more economical, more tonally-centered scale with only 29 pitches (because the more centered a microtonal scale is around a certain tonality, the more different pitches can serve as pivot notes among different harmonies). Having made another few pages like the above, I ordered the pitches and compiled them into a MIDI chart:

I generally seem to end up with scales of 29 or 30 pitches. With the kinds of harmonies I favor, more than that and I start to have pitches closer together than 15 cents, which I’ve found are a pain to work with, and when they’re within five cents (a 20th of a half-step), I just merge them, unless one is part of a perfect fifth I need in tune. Then I had to write out my MIDI-scale correspondences in musical notation:

and then group them into harmonic areas. In this case, upon doing so I realized that I had come up with two chords parallel and only 27 cents apart, a fourth of a half-step: too small to make meaningful distinctions between even in my music. I took a few hours off, doodled with fractions on the back of someone’s business card at dinner (you’d be amazed at how much of my composing takes place on the back of business cards and on restaurant napkins), and after an hour or two of analyzing gaps in the scale (a gap being anything more than 60 cents), I came up with a substitute chord – after which I had to take some pitches out of the scale, add new ones back in, and go through all but the first couple of steps all over again.Â

It used to be so much worse. At least now, with Lil Miss Scale Oven software, I can generate the scale and hear it played on a Kontakt softsynth in less than a minute; this part alone used to take about an hour. But I have to do all this before I can compose a note, and I still haven’t done the grouping into harmonics areas yet, which I leave for tomorrow. That’s not always true, because occasionally, as with my recent piece New Aunts, I just start composing in Sibelius, adding pitch bends to the notes and figuring out what pitches I want as I go along, though I tend to get greedy and end up with too many pitches that way, and have performance problems. (Also, those Sibelius pitch bends don’t always catch the onset of a note, so the audio result is full of irritating tiny glissandos.) In this case, I wanted a closed gamut for a longer, more involved piece. If you’re a microtonalist, also being a postminimalist helps.Â

But I love it. I have enough experience to savor in advance the pungent pitch-shifts I’ll get between harmonies, and the sound of the piece in my head really does guide me toward the right numbers, through a convoluted logical process. If you don’t have the head for this, and an intimate feel for numbers, you shouldn’t try it. I started studying just-intonation microtones with Ben Johnston in 1984, and didn’t finish my first microtonal piece until 1991, filling multiple notebooks during those years with hundreds of pages of fractions. I figure it delayed my composing career at least five years. I can’t even play you a sample yet because I’m several hours of work away from hearing the chords I’ve been hearing in my head. I guess it’s a little like the weeks of pre-planning the total serialists went through in the ’50s and ’60s, except that once I finish all the math work I can start composing freely from the chords and scales I have available. Often I compose from the charts without really knowing what pitches I’m using, just knowing what melodic contours and harmonic shifts will work, sort of like painting with seven-foot-long brushes and your back to the canvas – and mirabile dictu, it almost always sounds the way I’d imagined. Every microtonal piece I write takes about an intense week of all this before I can actually write notes. Afterward, it’s inspiring feeling that I’m doing something no one’s ever done before: but boy, is it obvious why no one’s ever done it.