I’m almost done transcribing and analyzing Dennis Johnson’s November, the ostensively six-hour 1959 piano piece that La Monte Young says inspired him to embark on The Well-Tuned Piano. I’ve listed some of November‘s innovations elsewhere. If it was indeed the first multi-hour continuous minimalist piece, the first tonal very slow work, the piece that pioneered additive process – and it may have been all that – those in themselves are enough to make it worth reviving and getting into the history books. But beyond that, I’ve become more and more impressed with its internal logic, which is almost mathematical (and Johnson left music to become a mathematician). The piece is organized into families of motifs based on the same pitches, which can proceed improvisatorily to other families of motifs at specified points. Johnson begins each new pitch field additively, bringing in one note or chord, then another, then another until they’re all present. But the overall formal concept is not simply additive but more like a series of circles, as each pitch field has a point of entry and exit, and within each section one can go back and forth among the motifs in that field. It’s really elegant, and in its glacial way makes a certain large-scale sense to the ear. Feldman’s wonderful masterpiece Triadic Memories (a much later work, 1981) is similar in its reminiscent effects and equally intuitive, but November is generally diatonic rather than chromatic, and its logic lies a little closer to the surface. I thought that in September Sarah Cahill and I would be re-premiering a kind of crazy, off-beat experiment of the late ’50s; instead I’m thinking we’ll be unveiling a whole new formal paradigm that deserved to have more of an after-history than it’s had.Â

Trying to Remember that Kind of November

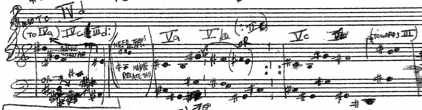

The performance notation has been a big problem. Johnson’s own manuscript:

is kind of a wonderful mess, full of arrows, cross-outs, and hesitant verbal directions sometimes taken back with the afterthought “No!” Still, the piece can be played from the ms. – if you’ve studied the recording closely and know how it works. (The recording contains only 100 minutes of the piece, marked by enigmatic discontinuities.) Renotating the piece to reflect the performance practice is perhaps the toughest musicological nut I’ve ever tried to crack. The piece can all be written in stemless noteheads, and should be, so that the performer isn’t lulled into observing some underlying pulse that isn’t there. And yet, the rhythm isn’t unimportant, because Johnson’s motifs fall into coherent and rhythmically characteristic phrases, and without those intuitive note groupings, the form won’t make any sense. I had to start with the tedious process of notating not only the pitches but the time placement of every note. My first method was to take a 5/4 measure, 8th-note = 60, and put the notes in ten-second measures grouped by sixes into minutes:

Still, this is an unnecessarily complicated notation for the pianist to read, and would result, I think, in a stilted performance. Plus, it doesn’t do anything for the four hours of the piece omitted from the recording. So I think what I’m going to do is finish writing it all out this laborious way, and then transfer all the notes by hand, as stemless noteheads, into proportional notation. Then Sarah and I (who will be alternating at the keyboard) will have the intuitive groupings to follow on the page. I’m also mapping motifs from the manuscript to the recording, so I can extrapolate to create some kind of performance score for the remaining four hours. The re-creation should preserve the recorded passages almost exactly, and if I do it right, the listener shouldn’t be able to tell when we switch from the re-creation of the recording to the improvised remainder of the score. I didn’t expect this to be one of the most rewarding things I’ve ever done.

In fact, as with my Harold Budd transcription, I’m looking forward to stealing some ideas for my own music. I’ve worked with a kind of terraced or altered additive process myself. My “Jupiter” movement from The Planets uses a slowly shifting additive form: AB, ABC, ABCD, BCD, BCDE, DEF, EFG, and so on. November is similar, but more circular and less linear in its process, and offers a methodology for building a much longer and more recurrent structure. So, say, instead of A, B, and C, you have A, A’, A”, A”’, and A”” leading back to A, then B, B’, B”, and so on. But F”’ might have a couple of pitches in common with B’, so that from here you have a portal back into the B material – large, formal reminiscences. How tragic it is that it’s taken almost half a century to rediscover all this – but how lucky I feel to get to do it!

Here’s a few minutes from the middle of the 1962 recording, to whet your appetite and show you what I’m up against.