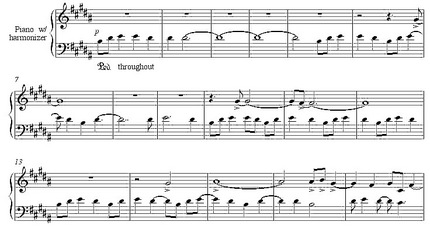

Differences between the two versions are rather spectacular. The Cantil version is five minutes long, the NMA version 23 minutes. The Cantil version begins like this:

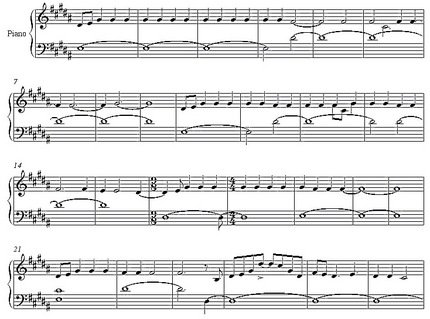

The live version begins like this:

Notice that the germinal motive of the recorded version is B-D#-E; that of the NMA version is D#-E-G#. The second motive is, of course, the inversion of the first. The Cantil version stays entirely within the B major scale, without a single accidental. The live version keeps shifting among major scales on B, D, and C#. In addition, the live version has a 12-minute middle section completely lacking in the recorded version, wildly rhapsodic with lots of arpeggios, and moving among major ninth chords on B, Db, D, Eb, E, F, and Gb, never jumping more than a minor third in root movement. This fast section is the hard part to transcribe, but I’m determined I can do it. The recorded version ends in G# natural minor, the live version in C#. On Cantil the lowest note is G# at the bottom of the bass clef, and the highest goes into the piano’s top octave. The live version descends to the lowest A# on the piano, but doesn’t venture as high.

In two diverse recordings of a jazz composition, we know what the identity of the piece consists of: the chord changes, perhaps a head melody. But in what does the identity of an improvised piece like Children on the Hill consist? The two versions have the following things in common: 1. Each begins and ends using a scale bounded by a B-major key signature. 2. Each revolves around a repeating motive of a major third adjacent to a half-step. 3. Each emphasizes repetitions on the F# and G# above middle C, with tonality directed to G# by an A#-B-G# motive. 4. Each climaxes melodically by leaping up to high D#s and G#s. 5. Each employs a consistent quarter-note and 8th-note momentum, except for the middle section of the live version, which is much freer. 6. Each employs different modes within the major scale by emphasizing certain drone notes: sometimes Aeolian, sometimes Lydian, sometimes Phrygian. And certain melodic motives recur in both renditions. Other than that, the identity of the piece can only be more felt than specified: a mood, a texture, an approach.

The recorded version has approximately the same weight, charm, and texture as Cage’s Dream or In a Landscape, and is worthy of them. The live version has all the gravity and formal ingenuity of a Beethoven sonata. I remember it was the first piece played at Navy Pier at the Chicago festival, and I (working as administrative assistant for the festival) arrived at the concert a couple of minutes late. I walked in, heard Budd playing, and stood in the doorway transfixed, as I’m still transfixed by the piece today. The texture looks a little thin on paper, but the harmonizer sustained all the piano tones and blurred them into a resonant wash. And in the fast arpeggio section, the music increasingly introduces melodies bitonally in the wrong key and resolves them by changing chord, a haunting effect. Budd was a tremendous influence on young West-Coast composers like Peter Garland and Michael Byron, and, through his recordings and from a greater distance, also on me. I hope this paper will demonstrate that the complexity and subtlety of not only his music, but his very conception of music, make him one of those minimalist composers who cannot possibly be shrugged off as simplistic.Â