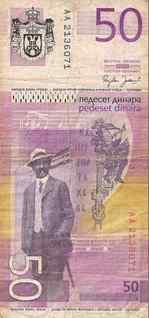

For instance, did you know that a Serbian composer, Vladan Radovanovic, claims to be the first minimalist composer, having started in 1957? (I’m really sorry that I can’t provide Serbian diacritical markings, but my word-processing software isn’t up-to-date enough to handle them, nor am I confident that Arts Journal could represent them.) Dragana runs into him occasionally, and he’s miffed that she hasn’t credited him yet. And here’s national composer Stevan Stojanovic Mokranjac, pictured on the country’s 50-dinar note (about a dollar):

(The 100-dinar note boasts national hero Nicola Tesla, who figured out a lot about electricity before Edison did.)

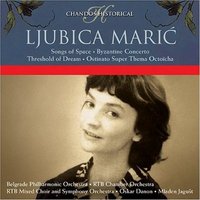

But easily the most fascinating story in Serbian music history is that of Ljubica Maric (1909-2003, pronounced Lyubitsa Marich, with a “ch” like church and accents on both first syllables). She was Serbia’s most important and innovative modernist composer before World War II. Now, how many other countries can claim that their pioneering modernist composer was a woman? Like, zero? Gotta hand it to Serbia. And, to be a chauvinist pig about it for a moment, early photos like the CD cover here show that Maric was just about the most beautiful composer in the history of music, strikingly modern-looking in the 1930s. She lived to be 94, and Dragana used to see her at concerts, but was too shy to speak to her.

But easily the most fascinating story in Serbian music history is that of Ljubica Maric (1909-2003, pronounced Lyubitsa Marich, with a “ch” like church and accents on both first syllables). She was Serbia’s most important and innovative modernist composer before World War II. Now, how many other countries can claim that their pioneering modernist composer was a woman? Like, zero? Gotta hand it to Serbia. And, to be a chauvinist pig about it for a moment, early photos like the CD cover here show that Maric was just about the most beautiful composer in the history of music, strikingly modern-looking in the 1930s. She lived to be 94, and Dragana used to see her at concerts, but was too shy to speak to her.

Maric studied with Josip Slavenski (1896-1955), who had absorbed Bartok’s ideas about incorporating folk music into symphonic music, and there is a strong Bartokian streak to Maric’s music, though the folk music influence is rarely obvious. She later studied in Prague with Alois Haba of quarter-tone fame, and wrote some quarter-tone music which is unfortunately lost. She got rave reviews for a wind quintet played in Amsterdam in 1933, and spent some time conducting the Prague Radio Symphony. But World War II interrupted her career, and afterward she was inhibited by Yugoslavian communism’s antipathy toward modernism, so that her total output is rather small. She revved up her muse again in the late 1950s, however, and the only works I’ve heard of hers, on the pictured Chandos disc, are from the period 1956-63. The most immediately engaging of them is her Ostinato Super Thema Octoicha (1963), which is based on a repertoire of Byzantine medieval religious songs called the Octoechos; I’ve uploaded an mp3 of it for you here. The Byzantine Piano Concerto and Sounds of Space contain remarkably beautiful and original passages as well; she very much had her own voice.

Teaching at the Stankovic School of Music and then at Belgrade Conservatory, Maric was into Zen and Taoism, and lived a reclusive life despite interest shown in her music by Shostakovich, among others. From 1964 to ’83 her pen fell silent, then she started composing again. She made some tape music performing on not only violin but cutlery, jewelry, and dentist’s equipment, but refrained from ever releasing it. She was a fascinating figure, Serbia’s Ives, Crawford, Bartok, and Cage all rolled into one. There’s a scholarly essay by musicologist Melita Milin about her career in the 1930s here. It all makes me think that the Balkan countries need to be more regularly incorporated into the historical narrative of 20th-century music.Â