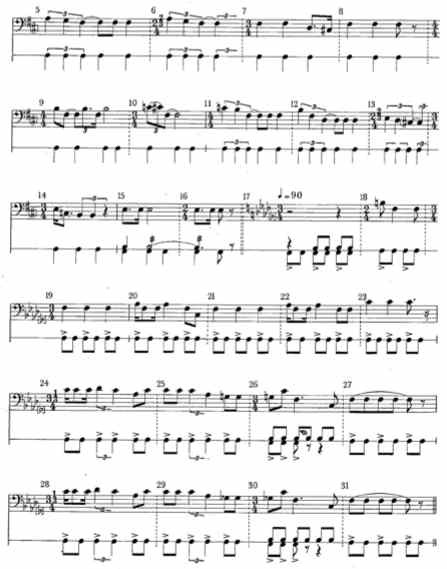

The meters, of course, aren’t given as 2/3 or 5/6, as they could be, but as 2 and 2/3 over 4 and 3 and 1/3 over 4 – a format Charles Ives also used. A somewhat similar Hopi Elk Dance song, in my own transcription, using dotted quarters and quarters instead of quarters and triplets, is given in my program notes to Desert Sonata, the 1994 piece that quotes the song.

Of course, the Zuni were not reading from sheet music, and one could quibble about whethere these incomplete triplets are the best way of rendering their music in notation – but as I saw it in 1977, this was a way of transferring that feeling of performance practice into music based in European notation. I wanted a musical basis that didn’t sound European, didn’t sound familiar, nor was rhythmic precision my aim. It has always seemed to me that dotted 8th-notes have an inherently syncopated feel, while triplet quarter-notes are much smoother, suspended over the felt beat, and I was interested in using the notation to induce different qualities, not only quantities, of rhythm. Performers who internalize that principle find my music easier to play than it looks at first. Steve Reich had arrived at his style by studying the Ewe drumming of Ghana, Riley and Glass by involvement with classical Indian music, Lou Harrison via Indonesian gamelan, and so on, and as someone who had grown up in the Southwest, I mined Zuni, Hopi, and Pueblo music for qualities that would help revitalize my tradition. During the 1990s there was a lot of criticism of white artists who “appropriated” music by people of color, and so I gradually backed off from the more programmatic aspects. Plus, increasing commissions from ensembles limited my style in rhythmic respects, while working with the Disklavier and electronics liberated it in other directions. This Zuni-Hopi influence survives in my music, but rather abstractly at this point.Â

In any case, to anyone who claims that incomplete triplets can’t be performed, I can always counter, “The Zuni can do it – why can’t you?”