Wow. WOW.

As you can infer, I am holding in my hands a copy of the score to Einstein on the Beach. I can hardly put it down. I ordered it from Chester Music, and it just came in the mail. I had come to think I would never own such a thing, because for so long Philip Glass had refused to release the music written for his ensemble, since performing it was how he made his money. But it’s finally available, and next semester I’m teaching an analysis class based on minimalism and its offshoots. So before I committed to the course, I searched around to see what minimalist scores I could get, and I found more by Glass and Terry Riley than I had thought would be available.

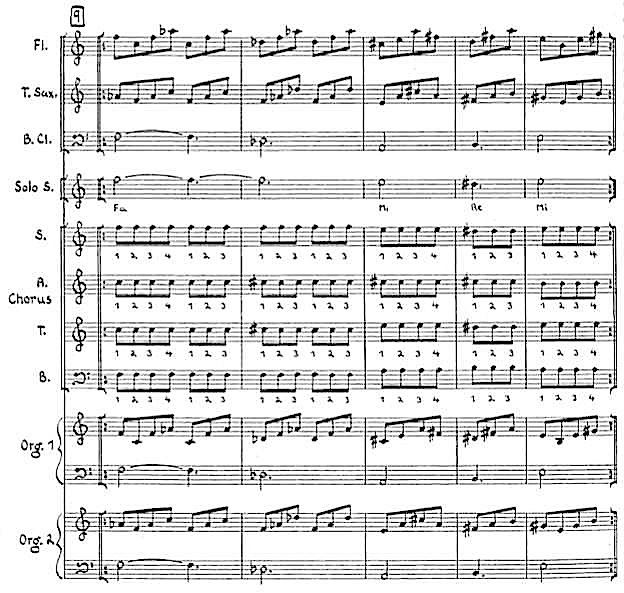

It’s not that I consider Einstein that great a piece – or at least consistently great – but it was crucially important in my development. The opera premiered on my 21st birthday (I wasn’t there), and I bought the Tomato recording about a year later, sometime in 1977-78. It was my first year of grad school, I had put my undergrad years behind me, and I was ready to embark on something new. You know what a deep impact new music encountered at that age can have. I never liked all of Einstein, was even irritated by some of it, but I wore that 4-record set down to slick vinyl wafers, trying to capture every process. What impressed me most was the difficult rhythmic patterns that Glass’s technique made available – and, trying to play through the keyboard parts in the score, they seem even more brain-twisting than I realized – and also the chromatic voice-leading among his harmonies. The “Bed” scene instilled in me a new conception of harmony that I use to this day. As I’ve reported before, years ago I had the opportunity to interview Phil in public, and told him that I was still trying to compose the “Bed” scene from Einstein. He replied, “So am I.”

So I think it’s only recently that a course in the analysis of minimalism has really become viable. I did receive a score of Dennis Johnson’s groundbreaking piano piece November, by the way, and with that, the score to The Well-Tuned Piano, the Boosey and Hawkes Steve Reich scores, Riley’s early string quartet pieces available from his web site, and what Phil Glass has now released, I think I can cover the early part of the movement. (Maybe we’ll try to dissect some Charlemagne Palestine by ear; he was pretty elusive when I quizzed him about scores.) Of course, some early minimalism is too transparent to be analyzed in any conventional sense. I’m not going to hand out the score to Music in Fifths to pore over a pattern that can be easily grasped in a minute or two. At the Music and Minimalism Conference in Wales last August, William Lake presented a thorough analysis of Riley’s In C, but making a larger statement about the work than the obvious one required more analytical prestidigitation than I can expect of my undergrads.

But I do think there are secrets of rhythm to be teased out from Einstein, a clear structure to be charted in Music for 18 Musicians and Octet, and afterward we’ll move on to some Phill Niblock frequency charts, John Adams’s Phrygian Gates, Duckworth’s Blue Rhythms, Lois Vierk’s Go Guitars, John Luther Adams’s Clouds of Forgetting, Clouds of Unknowing, Peter Garland’s Jornada del Muerto, and so on. Student enthusiasm has already been apparent. And this will all help me toward not only the book I’m writing, but the minimalism conference I’m directing with David MacIntire next year.

And by the way, Einstein: not a dynamic marking in the entire score.