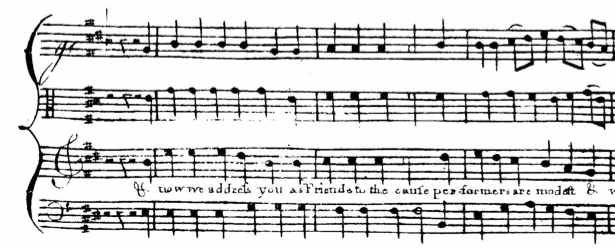

I love this score layout from William Billings’s hymn “Modern Musick” from The Psalm-Singer’s Amusement, originally published in 1781, a reprint of which I picked up at a used book store this week. Notice how the sharps in the key signature are written as much as possible straight up in a line, F-C-D-G:

Notice too how the note-stems are all on the right, and the treble clef in the soprano is indicated by a “g” on the second line. For awhile in college I wrote my treble clefs that way myself, on the reasoning that a treble clef is just an ornate Baroque Italian G written around the second line, and there was no reason for us to go on writing a “g” in that ridiculously festooned manner 300 years later when even the Italians don’t write them that way anymore. I had to choose my battles, I was destined to become engaged in so many, and I rather quickly gave that one up. But I love the insouciance with which the sacred order of sharps in a key signature is ignored, and how little difference it makes in reading the music.

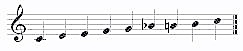

So many conventions of notating music we take as sacred, ancient, and unalterable are actually of relatively recent vintage, and used to be quite malleable. In Bach’s day the customary way of indicating a minor key indicated what we now think of as Dorian mode; for a violin suite in E minor he would notate two sharps, F and C. Nowadays, of course, we “correct” him, for old Bach clearly hadn’t taken first-year theory class. In the 1890s, theory textbooks (Rimsky-Korsakov’s, for example) taught the “harmonic major” scale:

based on the idea that the minor iv chord had become so common in major as to necessitate a special scale. Fashions come and go, theoretical premises change, but we teach notational conventions as though they are somehow ontologically necessary, and browbeat young musicians into a terrified conformity to which Billings was happily oblivious. Why? For efficiency’s sake, so that none of our orchestral musicians will ever have to encounter a piece of music that doesn’t look pretty much like every one they’ve ever seen, which otherwise might force them to actually pause and think a moment.

I had a friend many years ago, who died at a tragically young age. Bill Hogeland will know who I’m talking about. Right out of Oberlin she got a job as bassoonist for the Dallas Symphony. I saw her one morning, and she was tired because, she said, the orchestra had performed the night before.

“Oh, what did you play?,” I asked.

“Ummmm… Mahler, I think.”

She was a sweet young conservatory product, but her conception of her job was to prepare her reeds, sit down in her chair onstage, and expertly and automatically play the notes on the page some functionary had placed on her music stand, without ever thinking about who the composer was or what the notes meant. And to make sure that such nice people never have to think, never have to pause a moment and figure out anything they haven’t seen a million times before, our young composers have to have notational conformity beat into them on pain of excommuncation from all decent musical society. Yesterday a student brought me an orchestra piece with the following rhythm:

![]()

It’s a perfectly nice rhythm of a kind I might have well used myself. But not in an orchestra piece you don’t! I knew enough to put the kibosh on that. Because efficiency, sight-reading, automaticness, and thoughtlessness are at the heart of turning out classical music, that hallowed repertoire that Miles Davis so aptly termed “robot shit” – because it was played by robot musicians who couldn’t be bothered to deviate from or even think about what they saw on the page.

Don’t bother writing in to tell me how communist and retarded my opinions are, ’cause I already know what the robots think of me. I’m an evolutionist, who thinks music has evolved and has a right to keep evolving, whereas most classical musicians are creationists who think Beethoven created it 200 years ago and it has to stay that way eternally. As Mark Twain said, “I don’t give a damn for a man who can only spell a word one way.”