[Update below] I’ve been intending to write more about my European sabbatical, but I’m rather frantically composing on deadline. I have five world premieres coming up in the next several months, and two of the pieces aren’t finished. Thanks to my extended leave from teaching, I wrote seven works in 2007, totaling some 85 minutes of music – not much by some people’s standards, but a personal record for me. And I have two movements of The Planets to finish before school starts, so that the Relache ensemble can start practicing the entire 75-minute, ten-movement work – my own Turangalila, I like to think of it as – for their performance in Delaware in May. Also, my European trip was a lot to process: seven countries in eleven weeks, giving six concerts and ten lectures, meeting lots of composers, and hearing tons of new music. Unlike the American businessmen in novels, every American artist goes to Europe hoping to be changed. I’m not sure I was, but I did need time to think about it.

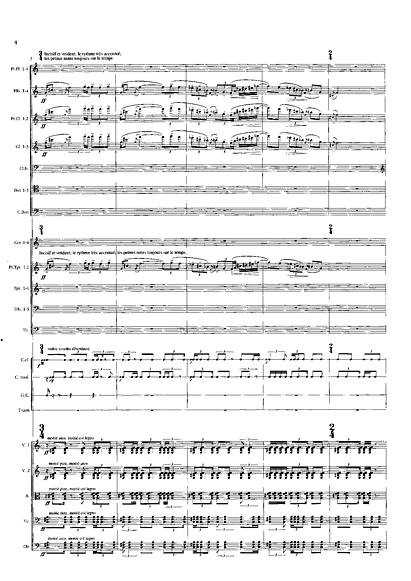

What I can do, though, is tell you about the most astonishing composer I learned about there: Matthijs Vermeulen. The Dutch call Vermeulen (1888-1967) “the Charles Ives of Holland,” and also their Varèse. He is the archetypal undiscovered composer. His Second Symphony – considered by many his most groundbreaking work (second page pictured below) – received its first performance in 1953, and Vermeulen himself first heard it in 1956. He had written it in 1920. The tone clusters, polyrhythms, percussion, and atonal counterpoint it opens with are easily as daring as anything Varèse would write in the next decade. To throw yet another comparison in, the Dutch refer to it as “the Dutch Sacre du Printemps.” Curiously modest about promoting their national composers, they won’t tell you anything about Vermeulen unless pressed, but if you mention how remarkable he was, they look proud as punch.

What I can do, though, is tell you about the most astonishing composer I learned about there: Matthijs Vermeulen. The Dutch call Vermeulen (1888-1967) “the Charles Ives of Holland,” and also their Varèse. He is the archetypal undiscovered composer. His Second Symphony – considered by many his most groundbreaking work (second page pictured below) – received its first performance in 1953, and Vermeulen himself first heard it in 1956. He had written it in 1920. The tone clusters, polyrhythms, percussion, and atonal counterpoint it opens with are easily as daring as anything Varèse would write in the next decade. To throw yet another comparison in, the Dutch refer to it as “the Dutch Sacre du Printemps.” Curiously modest about promoting their national composers, they won’t tell you anything about Vermeulen unless pressed, but if you mention how remarkable he was, they look proud as punch.

On top of the fact that he was decades ahead of his time, Vermeulen was just my kind of guy. Autodidact and too poor to buy concert tickets, he learned the repertoire by listening to orchestras play from outside the Concertgebouw, sitting in the garden. He found work as a music critic, one whose sharp and outspoken views earned him enemies and injured his chances for performance. (My apartment in Amsterdam was about six blocks from the Concertgebouw. After romanticizing the place for my entire life, I was pretty let down to find that it simply translates as “Concert Building.”)

The most famous incident of Vermeulen’s life, the one every commentator mentions, occurred while he was working as a critic in November of 1918. Following a performance at the Concertgebouw of the Seventh Symphony of the rather conservative Dutch composer Cornelius Dopper, Vermeulen, to express his contempt, yelled “Long live Sousa!” – by which he meant that even the little-respected John Philip Sousa was a better composer than Dopper. Much of the audience understood him, however, to have shouted “Long live Troelstra!”, which was the name of a socialist revolutionary who had attempted to start an uprising only days before. For awhile Vermeulen was banned from the Concertgebouw by the orchestra’s management. Unable to make a living in Amsterdam, he moved to Paris for a 25-year exile, eking out a living as a music journalist and travel writer. You can see why my heart goes out to the guy. I have a feeling Vermeulen and I would have been thick as thieves.

After World War II, and the war-related deaths of his wife and son, Vermeulen moved back to Amsterdam, and his works started to be heard. There is a “Complete Matthijs Vermeulen Edition” of his recordings on two three-CD sets on Donemus, sold in every record store in Amsterdam but rather difficult to locate on internet retail outlets. His twenty-odd works are easily listed:

Symphonies:

No. 1, “Symphonia carminum” (1912-14)

No. 2, “Prelude à la nouvelle journée” (1919-20)

No. 3, “Thrène et Péan” (1921-22)

No. 4, “Les victoires” (1940-41)

No. 5, “Les lendemains chantants” (1941-5)

No. 6, “Les minutes heureuses” (1956-8)

No. 7, “Dithyrambes pour les temps à venir” (1963-5)Chamber music:

Cello Sonata No. 1 (1918)

String Trio (1923)

Violin Sonata (1924)

Cello Sonata No. 2 (1938)

String Quartet (1960-61)Songs with piano:

On ne passe pas (1917)

The Soldier (1917)

Les filles du roi d’Espagne (1917)

Le veille (1917; also in orchestral version of 1932)

Trois salutations à Notre Dame (1941)

Le balcon (1944)

Preludes des origines (1959)

Trois chants d’amour (1962)Other:

Symphonic Prologue, Passacaglia, Cortège, and Interlude to The Flying Dutchman (1930)

That’s it: Vermeulen’s life’s work. The symphonies – only the Fifth of which is divided into movements – are amazing. All of his music is tremendously contrapuntal, with many lines competing in a vast rhythmic heterophony. Throughout his life he complained that musicians who looked at his scores warned that the music would never sound, but that no one would play it to prove the point – and when he finally heard his works, they sounded just the way he wanted. He flows back and forth across the threshhold of tonality and atonality, occasionally sounding like Ives or Ruggles depending, though really sounding very much like himself. One of his most lovely and characteristic effects is the atonal (or dissonant) background ostinato, over which lengthy melodies unfold. It’s complex music, difficult to become familiar with, but not at all without personality. In weight and density one might compare the symphonies to those of Karl Amadeus Hartmann, although they are not nearly so complicated in form as Hartmann’s, and easier to take in as a whole.

I was directed to Vermeulen by a casual comment from Anthony Fiumara, director of the Orkest de Volharding. The name was totally unknown to me. I would have never believed that I, lifelong connoisseur of obscure composers, someone who teaches Berwald and Dussek in the classroom, would discover, at 51, a major composer I had never heard of, let alone one who would quickly become one of my favorites. At Donemus I bought the scores to the Second, Third, and Sixth Symphonies. It turns out that my erstwhile Fanfare magazine colleague Paul Rapoport wrote a book titled Six Composers from Northern Europe, about Vermeulen, Vagn Holmboe, Havergal Brian, Allan Pettersson, Fartein Valen, and Kaikhosru Sorabji, which remains one of the fuller treatments of Vermeulen in English; the one existing biography is only in Dutch. And since I hate to tell you about any music you can’t hear, I upload Vermeulen’s Third Symphony for your listening pleasure. Keep in mind it was completed in 1922. It’s amazing what you can reach your fifties without knowing, but delightful to realize how much left there is to learn.

UPDATE: I found an insightful and thorough article on Vermeulen here.