AMSTERDAM – I’m not over here just turning European musical society on its ear, you know. In fact, I don’t seem to be doing that at all. I haven’t yet had to place a revolver on the piano to quell potential riots, the way Antheil did when he came to Europe – audiences here have simmered down over the years. But besides performing and lecturing, I’m also working on my book, whose title had already changed from Music After Minimalism to Music After the-Music-Formerly-Known-as-Minimalism, and now may have to be titled The-Music-Formerly-Known-as-Minimalism and its Aftermath. Oh, I know what you’ll say, that if I wanted to research American music I could have stayed and done that in America. But that’s just what they were expecting me to do. No no, the thing to do, obviously, was to load everything on my hard drive and come study it over here, so I can give it the faux-expat perspective.

The latest title change is due to my realization that I can’t simply begin my story in 1978 and build it on the current absurd caricature of what the general public thinks minimalism is, as revealed at Wikipedia and elsewhere. I don’t want to spend a lot of time on well-traveled territory like Music for 18 Musicians and In C, but I do have to give enough of minimalism’s early history to clarify that it was more of a 20- or 30-composer movement, not just a four-composer movement, as the public thinks (nor a 500-composer movement, as Wikipedia’s indiscriminating savants imagine). I can’t explain postminimalism to people who will assume that what the postminimalists were reacting to was The Death of Klinghoffer; nor can I fully clarify Peter Garland, Larry Polansky, and Band of Susans to people who don’t know the crucial contributions to minimalism made by Harold Budd, Jim Tenney, and Phill Niblock. And so I’m getting resigned to greatly expanding the section on minimalism, which will also make the book more marketable to publishers, since books on minimalism already exist, and publishers are petrified of taking chances on anything that threatens to convey too much new information. By temperament, new information is the only kind I enjoy imparting.

Toward this end, one of the projects I’m enjoying working on is transcribing little-known minimalist keyboard works. Some minimalism was improvisatory, and even some that wasn’t is documented only by recording. At the moment I’m working on November by Dennis Johnson, the 1959 piano piece that La Monte Young credits as having inspired The Well-Tuned Piano. Johnson was one of a trio of students at UCLA in the late 1950s who were exploring La Monte’s idea of slow, static music, along with La Monte himself and Terry Jennings. Terry Riley joined in soon afterward. Johnson figures heavily in La Monte’s semi-famous “Lecture 1960,” and is also credited with (among several conceptual pieces, including one that consisted of just the word LISTEN), a work titled The Second Machine that uses only four pitches drawn from La Monte’s Trio for Strings. Soon afterward, however, Johnson abandoned music and went into computer science. November seems to have been the magnum opus of a heavily abbreviated career.

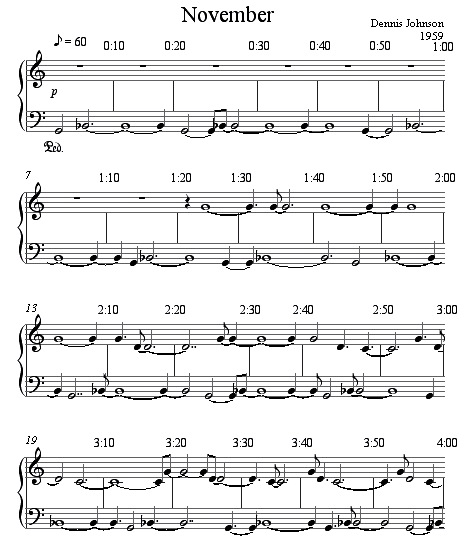

At one point La Monte mentions that November was “theoretically” six hours long. The hiss-filled, barely audible surviving recording, however, made on reel-to-reel by Jennings and Johnson (which I’ve never played on Postclassic Radio because the quality just doesn’t make for pleasant listening), cuts off abruptly after 100 minutes. It’s slow enough that one could almost take all the pitches down in dictation in real time, but I’m trying to painstakingly document all the exact rhythms in order to facilitate replicating the performance. Below, I give the first four minutes of the piece, but this isn’t a good notational solution: what I want to use eventually is just stemless noteheads proportionally spaced, but I’m not sure I can do that in Sibelius. Still, I’ve played this excerpt (on Sibelius) simultaneously with the original recording, and the notes line up almost exactly:

We can’t ask Dennis Johnson about it: he’s disappeared. La Monte’s last e-mail from him said that he was sick and tired of battling internet problems, giving up on the 20th century, and going out of e-mail contact. He lived in California, and at one point lost his house in one of those humungous wildfires they have out there, and if there ever was a score to November (as La Monte thinks there was, but doesn’t remember much about it), it’s probably lost. Jennings, of course, died long ago. So it’s just me and the recording, on our own.

If anyone knows of Dennis Johnson’s whereabouts, please get in touch.

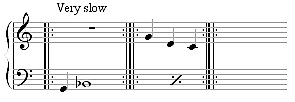

But think about what was going on musically in 1959, look at the example above, and tell me that wasn’t a radical thing to come up with. The classical world was pretty much divided up at the time among the crazy-mathematical 12-toners, the chance-obsessed Cageists – both groups resolutely atonal – and the neoclassicists who were still writing huge, brass-climaxing symphonies. Feldman was writing slow, soft music, and as late as 1965 Jennings’s slow music was atonal and rather Feldmanish. But November caresses a spare, sad G minor from the piano, protominimalist in both diatonic tonality and repetitiveness. Keep in mind that in the above notation I’m trying to preserve the specific performance, not recreate the score. There is no reason to assume every note was notated: the entire first five and a half minutes of the score might easily have boiled down to this:

And look how many aspects of later music the piece anticipates:

1. Diatonic tonality. The standard minimalist line is that Terry Riley reintroduced diatonic tonality into minimalism with his String Quartet of 1960, but this turns out not to be true. That mythic quartet wasn’t in circulation until recently, and I and other scholars were misled by Edward Strickland’s Minimalism: Origins book into characterizing it as being in C major, but what Strickland evidently meant was merely that it had no key signature. Musicologist Ann Glazer Niren corrected this notion in her talk at the recent Minimalism conference in Bangor, and played some excerpts of the piece, which is basically atonal, though entirely soft in dynamics. (Keith Potter’s book gets the facts right, too, but without examples.) Riley’s diatonic music came later, first toyed with in a May, 1961, String Trio, later developed in In C (1964) and the ensuing Keyboard Studies. (There is an important precedent for diatonicism, of course, in Cage’s piano pieces of the 1940s like In a Landscape and Dream, and some of Lou Harrison’s pieces as well, but it’s unclear whether these had any impact on the early minimalists.)

2. Phrase repetition, which Johnson does not seem to have picked up from La Monte, though he did follow La Monte in using slow tempos.

3. Additive process – since each phrase adds more and more notes as it repeats, in a manner that La Monte would later use in an odd little 1961 requiem called Death Chant (with the same pitches: G, Bb, C, D), but more famously adopted as the method of Phil Glass’s early minimalist works.

Plus, there are other aspects specifically relevant to The Well-Tuned Piano:

4. First of all, the idea of letting a continuous piano piece run six hours, if indeed November was originally that long.

5. The very gradual introduction of new pitches, which is The Well-Tuned Piano‘s recurring M.O.; and,

6. the partitioning of a long piece into various contrasting pitch regions. At 9:37 in the recording, November adds in E and F# as the initial transition to a kind of B-minorish area. This is also almost exactly the point in the 1981 Well-Tuned Piano recording at which the music begins to move from the Opening Chord (on Eb) to the Magic Chord (on F#); the coincidence itself is insignificant, because the onset of that transition varies from performance to performance, but it points up how closely Johnson’s harmonic conception anticipated La Monte’s.

7. Plus, IF the piece wasn’t fully notated – and that’s an if we probably can’t resolve – it would have given La Monte a model for a piano solo only indeterminately notated.

Of course, November is for conventionally tuned piano (Tony Conrad brought just intonation into the mix somewhat later), achieves no powerful acoustic overtone effects, employs no elaborate over-arching thematic scheme (at least, not one observable in the first 100 minutes), and is not the mind-blowing, sumptuously evolved masterpiece that The Well-Tuned Piano eventually became. Nevertheless, it is monumental on its own terms, and certainly marks more historic firsts than we have a right to expect from any one piece. And until we revive what’s left of it, which I hope to do in both performance and an article for the next minimalism conference, we miss a key piece of the puzzle of how minimalism sprang into existence.

Another spare-moment project I’m undertaking, incidentally, is a transcription of Harold Budd’s 1982 New Music America performance of Children on the Hill, one of the most gorgeous things I’ve ever been present for. Though well preserved, that’s another tape not suitable for public consumption because a remarkably loud and obnoxious baby, seemingly closer to the mike than Budd was, wailed like a demon through 50 percent of it. That kid’s about 25 now, and I hope he finally got whatever it was he wanted. Budd recorded Children on the Hill for one of his early, Eno-produced records too, but that’s a stripped-down five-minute version; at NMA he extemporized gloriously for 23 minutes. Some of the best minimalism ever made is still languishing away on private tapes.