The idea of different-length loops running at the same time and going out of phase with each other, which I wrote about in the Totalistically Tenney post, is one I’ve been working with for more than three decades. It would be, if anyone knew much about my music, the idea with which I am most associated. I first used it in 1975 in Satie, my Opus 1, so to speak (here the loops are 11 against 19 against 6, as measured in 8th-notes, and the upper lines use a note-permutation technique that I later learned Jon Gibson and Barbara Benary were using as well):

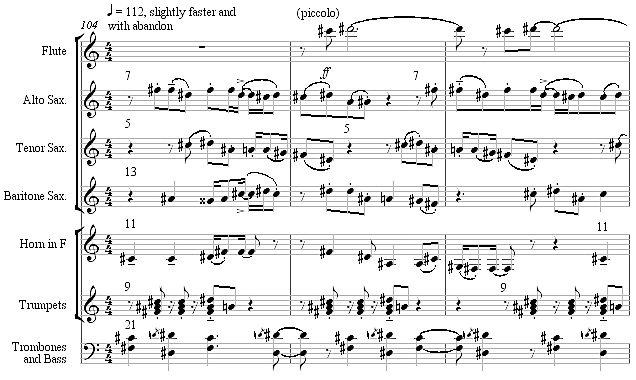

and most recently in Sunken City, the piano concerto I just completed (with indicated loops of 7, 5, 13, 11, 9, and 21 quarter-notes):

In between it’s been the basis of perhaps half the pieces I’ve written, and the most characteristic half at that. Most people I mention my piano concerto to ask me if I retuned the piano. I guess everyone associates me with microtonality, but only about a third of my music is microtonal, including almost none of the acoustic music, and rhythm has always been more crucial to my music than pitch. I became electrified by microtones in 1984, but my fascination with polytempo goes back to 1969, the year I discovered Three Places in New England, and I have rarely written a piece in which the primary interest wasn’t rhythmic.

And so much of my music uses repeated phrases of different lengths, played at the same time. The question is, what does it do for me? And even before that, what do I call the idea? I sometimes refer to my “nonsynchronous simultaneous loops,” which is a horrific phrase; no antibiotic has so off-putting a moniker. I wish someone would come up with a name for my particular -ism, but I am reluctant to do so myself, even though I am far from being the only person to widely explore the idea. In any case, out-of-sync-loopism is not an inherently rewarding device. Unlike the gradual phase-shifting Reich discovered, it does not immediately arrest the ear. Unlike the 12-tone row, it does not offer any theoretical guarantee of deep underlying unity. In fact, it’s a difficult idea to make work. As you can see from the first example, Satie, it’s pretty easy to do if you want to float around in an unresolving, unchanging, pandiatonic cloud, which was the first solution I came up with. That much is easy, but it didn’t satisfy me for long.

The idea of out-of-sync loops has many roots, all of them (so far as I know), American, although it would probably be possible to cherry-pick examples from The Rite of Spring. Henry Cowell implies the device in New Musical Resources, and momentary examples are common in Ives. Nancarrow’s early music bristles with the device, especially Studies Nos. 3, 5, and 9; but I was already using it in 1975, and heard none of Nancarrow’s music until the New World recording came out in 1976. The other root for the technique is easy to overlook: it is John Cage, for if you start a couple of loops repeating against each other, and agree in advance to accept whatever unforeseen clashes and unisons arithmetically result, that’s much like accepting the results of a chance process. And it was originally a strong interest in Cage that made me willing to repeat a 31-beat melody against a 43-beat melody and be willing to accept whatever dissonances and consonances would eventually arise from their relatively unforeseeable combinations.

And so I’ve worked with the idea, and worked with it, and worked with it, and some of the attempts have been disastrous, others merely dull, and a few glorious. Blake’s inspiring line, “If the fool would persist in his folly, he would become wise,” has always been my motto, and I have exhibited a stubborn Scorpio persistance in my faith in this device that the consequences alone would never have justified. Set a bunch of repeating loops going, and certain uninteresting eventualities are virtually guaranteed. Take a loop of 11 beats against one of 13: in 143 beats they will have cycled through every possible combination, and unless you’ve calculated shrewdly, some of the results are bound to be awkward or redundant. In addition, the music is guaranteed to remain fairly static: the device generates ever-new combinations for awhile, especially if you have enough lines going, but the component materials themselves never change. A lot of the effect depends on what numbers you pick. Back in the ’80s, I leaned on the Cagean aspect of the idea, with loops of 103 beats against 173 against 211 (all prime, of course), so that truly unplanned combinations would result. More recently, I use smaller numbers to create a more audibly pulsing texture, and play free and loose with harmonic alterations to ensure more surface interest.

Still, between the Scylla of unpredictable collisions and the Charybdis of predictably unvarying content, the out-of-sync loop device would seem to harbor more pitfalls than advantages. I have to ask myself, from time to time, why I keep trying to make it work; and I answer myself here, not only in the quest for self-knowledge, but because I’m giving a paper on this subject at a minimalism conference at the end of August, and I need to be able to explain not only why I but why other composers have been so fascinated by this problematic paradigm.

Number 1: it relates to some vague idea we all have of the medieval Music of the Spheres. Watching the 19-year cycle of the moon’s orbit go out of phase with our revolution around the sun is a primordial human experience: too slow to observe on a weekly basis, but crucial for agriculture and calendar-making. The visible planets Mars, Saturn, and Jupiter also exhibit phasing relationships against the background of the stars, and the cycles of those planets (along with the invisible orbits of Uranus, Neptune, and Pluto) connect the nonsynchronous-looping idea with astrology. So looping at different rates has a deep philosophical connection with our experience of the moon and other planets. Certainly some of my interest in the idea was encouraged by all the grad-school work I did in medieval music, in which the Music of the Spheres was a potent theoretical paradigm.

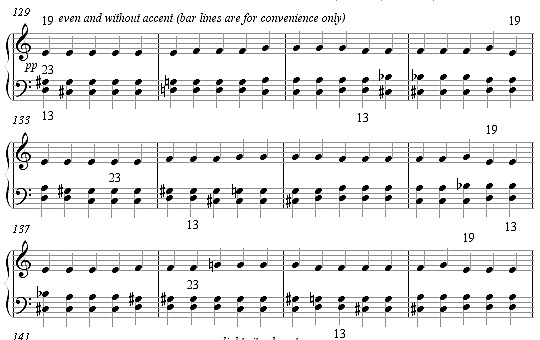

Number 2: Looping segments of different lengths is one way to create a static musical texture without allowing any literal repetition. A couple of my pieces, like Windows to Infinity (1988) and Cosmic Boogie-Woogie (2000-1) employ the idea mechanically, and thus would eventually begin repeating literally if played for thousands of years. I am not much interested in literal repetition, but I am very partial to pieces that never stray from their opening premises. In some pieces I have learned how to use lines that inflect the harmony chromatically, so that the confluence of loops doesn’t limit me to a static pandiatonicism. My favorite such passage is one in plain quarter-notes from Time Does Not Exist (2001) (with loops of 13 against 19 against 23):

Number 3: It’s a way to suggest the idea of different tempos at the same time in an ensemble context without actually asking people to play at different tempos. In the early ’80s I was writing pieces (Long Night being about the only successful one) in which performers watched silent, blinking metronomes to play repeating phrases at different tempos. And of course, several of my Disklavier pieces, most notably Unquiet Night, use the idea with actual polytempos.

Number 4: It allows for a feeling of pulse, but destroys any overriding sense of regular meter. There is a vague sense of melodies, high notes, rhythmic motives, recurring; but since each line recurs at a different place with respect to the others at every repetition, there is a non-metric wash to the sound that, when it really works, I find rather ecstatically trancelike.

Number 5: Morton Feldman was inspired by the mobiles of Alexander Calder to write pieces in which various repeating motives float by one another in continually changing temporal relationships. Why Patterns? is a particularly clear example. As far as I know, all such instances in Feldman’s music allow the players to play at their own rate, unsynchronized, so that exact relationships among the repeating figures are, in a detailed sense, unpredictable. Using repeating loops in a synchronized, metric context allows one greater control over the resulting relationships. There is, of course, no strong reason to maintain a mechanical rate of repetition, and in recent years I have sometimes only approximated the effect, conveniently avoiding unwanted clashes.

For me, these are potent philosophical, psychological, practical, and perceptual reasons to continue trying to make the idea work. It has often not worked, and (like Cage with his chance processes) I have often had to revise and revise until I liked the results. One of my best successes, I think, is in the last movement of Transcendental Sonnets, in which the entire orchestral texture (except for the climax about 3/4 of the way through) is pervaded by nonsynchronous loops, filtered through periodic changes in harmony; you can hear the result here. Every few years I seem to make some breakthrough to a more effective use of the idea. Out-of-phase loops can also be heard in Mikel Rouse’s songs of the 1990s, and in Michael Gordon’s pieces of the same period, like Yo Shakespeare (1993) and Trance (1995); and one can, of course, find similar ideas – usually with only the rhythms looped, and not the pitches – in the musics of John Luther Adams, Art Jarvinen, Joshua Fried, Diana Meckley, Larry Polansky, Evan Ziporyn, Eve Beglarian, Rhys Chatham, Glenn Branca, and others. I’m afraid I’m probably fated to keep working with the technique. It’s like the speck of dirt that gets into an oyster, irritating him until he builds a pearl around it.