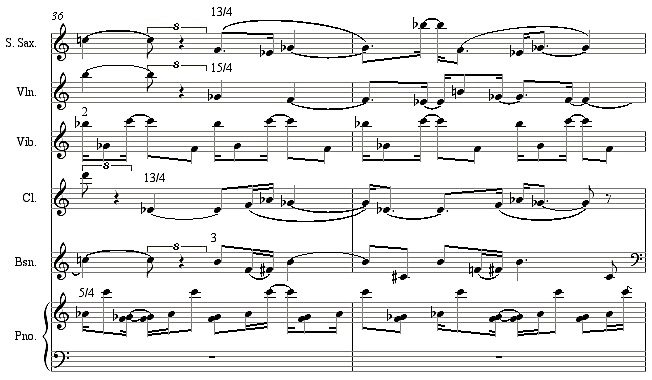

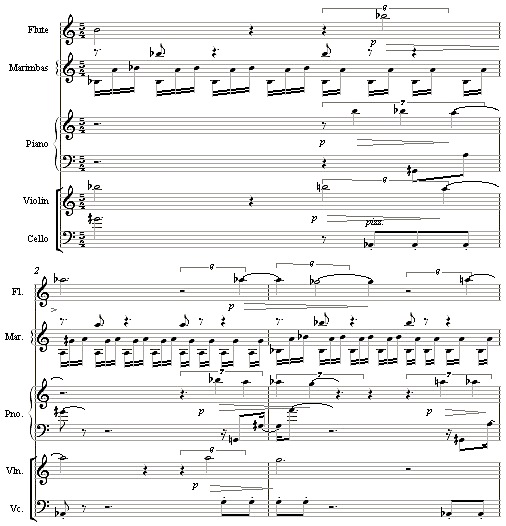

I spoke in my last post of James Tenney’s postminimalist streak, which I have always most associated with his Tableaux Vivants of 1990. A few years ago, learning of my intense interest in the piece, Jim kindly sent me a score, and I’ve long itched to analyze it, never finding the time until this week. As I start working my way through it, I realize that it is far more complex than it sounds on the recording by the Toronto ensemble Sound Pressure, and that it is really not postminimalist at all, but rather classically totalist, or, as we now call it here, metametric. It is unusual for Tenney in being composed mostly of repeated phrases, and in that those phrases loop at different lengths to create a counterpoint of recurring impulses at different speeds (or rather a “harmony of phrase lengths,” as Cowell would have said). The piece sounds gently undulating, not as wild as it looks, because of its uniformly soft dynamic level. May Doug McLennan and those with dial-up modems forgive me, but I’m going to post several measures of this 20-minute work here. All I’ve added, in numbers above each new phrase, is the length of the phrase expressed in beats (i.e., 11/3 = 11/3 of a quarter-note long, or 3 and 2/3 beats):

As you can see, or figure out anyway:

the first “moment” in mm. 34-35 forms lines in triplet 8th-notes, to make repeating periodicities of 5 against 7 against 11;

mm. 36-37 move to a 16th-note common unit for phrase/phase relationships of 5 against 12 against 13 against 15 (12 being the clarinet line three beats long);

m. 38 changes back to triplets for loops of 3 (piano) against 8 (violin) against 9 (clarinet) against 13 (bassoon) against 16 (sax);

and in mm. 40-42, a trio pursues phrase loops of 15 against 17 against 25 in 16th-notes. Notice that this last passage is entirely within the B-flat major scale.

I’ve posted Sound Pressure’s recording of the piece here. The excerpt given above begins at 2:18, immediately following the first sustained vibe-and-piano chord.

In his program notes, Jim calls the piece an attempt “to resume the exploration of harmony in the twentieth century without regressing to some earlier style….” He alludes to stochastic processes, by which I imagine he means the way the pitches are chosen, which seems somewhat random from “moment” to “moment”: the instruments overlap in pitch considerably (which puts the bassoon, you’ll notice, in an incredibly high register even above Le Sacre du Printemps), and the harmonies range from quite tonal to sharply dissonant. I take this to mean that the harmonic aspect of the piece is not susceptible to conventional analysis; if anyone knows more about the piece in this (or any other) respect, I’d appreciate some sharing of information.

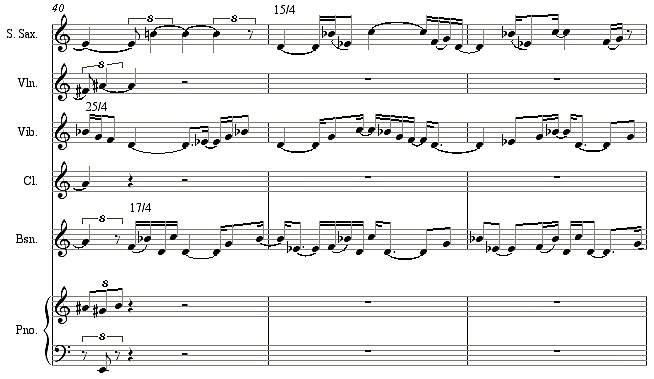

What surprises me most is the use of repeated motives in lengths not divisible by the quarter-note beat to create an effect of conflicting periodicities not based on the beat, and also a kind of gear-shifting effect, as those periodicities switch among lengths like 13/3, 3, and 15/4, quite akin to what totalists like Michael Gordon, Mikel Rouse, and myself were doing in the ’80s and ’90s. Compare it, for instance to this gear-shifting effect, also using “misaccented” triplets to change the perceived pulse, from my Snake Dance No. 2 (1994) for unpitched percussion:

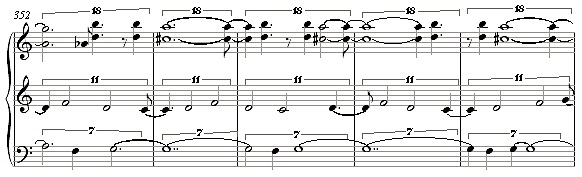

Then with this passage from my Unquiet Night (2004) for Disklavier, which combines periodicities of 21/13 of a measure (top system), 16/11 of a measure, and 13/7 of a measure:

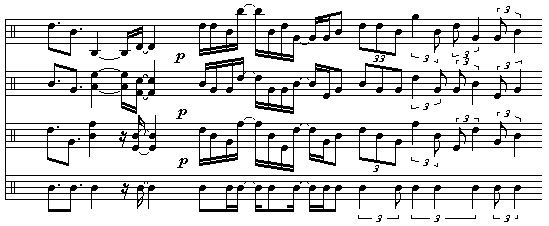

Then look at this passage near the end of Bunita Marcus’s chromatically saturated Adam and Eve (1987), with its implied periodicities slightly longer than a measure in the piano, violin, and flute, and an impression of layered tempos created by both triplets and septuplets:

It so happens I still have Adam and Eve on my web site, so you can hear it here; the excerpt above comes late in the piece.

Next here’s an excerpt from Michael Gordon’s Yo Shakespeare (1993 – mp3 on my web site here). The little threes above the top system indicate triplet quarter notes, even though other notes are interpolated between them; the grouping of triplets in quantities indivisible by three was a potential Henry Cowell pointed to in New Musical Resources, which I also tried out in my Folk Dance for Henry Cowell (1997). I don’t even know what instruments these are in Michael’s score, because my old copy was pre-publication, but each line is doubled. The top system gives a repeating rhythm 7/3 beats long in quarter notes, the middle line has a rhythmic pattern 7 16th-notes long (7/4 of a beat), and the bottom repeating phrase is five beats long:

And we can even find the same basic idea in easier, more orchestrally digestible form in John Adams’s Lollapalooza (1995), one of his most totalist works. Here a three-beat ostinato in the bass clarinet marks a steady tempo against which the other instruments repeat ornamental phrases at various periodicities, including the title “Lollapalooza” motive every five beats in the triombones and tuba (score greatly simplified and much material omitted):

I’d like to think that Adams was inspired to play with loops-out-of-phase by listening to the younger generation, but he could well have absorbed the same technique from Nancarrow, whose music he has championed, and whose Studies Nos. 3, 5, and 9 in particular experiment with a similar device. Another example could be John Luther Adams’s Dream in White on White (1992), which carries out the idea at lengths too great to quote in notation here. Even I’ve got limits.

In any case, I was pleasantly surprised to find Tenney playing around with the same metametric concerns as me and my totalist crowd. Any info about Tableaux Vivants would be much appreciated. Perhaps he even has other similar pieces, I’m certainly not familiar with his entire output. The examples above will be raw material not only for my Music After Minimalism book, but for a paper I’m presenting (“Phase-Shifting as an American Compositional Temptation”) in September at a minimlism conference at the University of Bangor in Wales.