Someday someone will appear who has analyzed more minimalist-influenced music from the 1980s and ’90s than I have, and if that person feels that I have divided my era into categories inappropriately, I will be glad to listen to her argument. So far, I’ve gotten plenty of argument, but only from people who don’t come anywhere close to fitting that description.

There are several ways to characterize a style. One is to catalogue all relevant qualities associated with pieces associated with that style. I’ve done this for postminimalism elsewhere, and I have no intention of replicating that feat today. Another, less cautious tactic is to isolate a compositional aim that one perceives as the essence of a style. This has the disadvantage of marginalizing (or at least discategorizing) pieces that do not manifest that particular idea, for artistic styles, it seems to me, are rarely homogenous in their makeup. Nevertheless, if I had to point to one characteristic that strikes me as quintessential to postminimalism, it would be the impulse to write music freely and intuitively within a markedly circumscribed set of materials, outside of which the piece “knows in advance” it will not venture. For me, and reinforced by the contemporaneous writings of Steve Reich, minimalism’s essence was its quasi-objectivity, its linear movement from one point to another, along with its adherence to audible process or structure. Postminimalism at once became much more subjective, often even mysterious, imitating minimalism’s extreme limitation of resources but replacing the idea of linear, audible structure with that of a nuanced, intuitive musical language.

For instance: Several movements of Bill Duckworth’s Time Curve Preludes (1978-79) fit this paradigm exactly. Not all of them, for Time Curve Preludes is something of a transitional work, and several movements preserve the idea of additive and subtractive process that I think of as continuing minimalist practice. Prelude No. 7 is a movement that strikes me as the postminimalist piece par excellence:

This languorous dance is made up of only three elements: a slowly arpeggiated bass line whose final dyad sometimes gets extended (A); a melody that here and there breaks the continuity (B); and a set of six chords that create an impression of bitonality by wandering conjunctly through scales from various keys, though the lower two lines are not actually diatonic (C):

There is some inheritance from minimalism here in the systematic way the phrase lengths expand at first according to lengths proportional to the Fibonacci series, but even this structural element recedes as the B melody intrudes more and more. You can listen to the movement here. I don’t think of the Time Curve Preludes as Bill’s best piece any more than I think of In C as Terry Riley’s best piece, but they are parallel in that they seem to be their respective composers’ most memorable pieces, the ones everyone knows, the ones whose perfectly clear intentions serve as a manifesto, of which their subsequent music works out the ramifications.

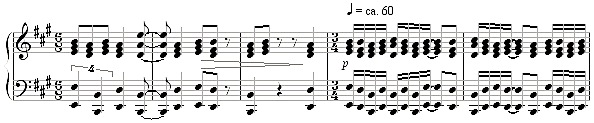

Even more restrictive in their materials are some of Peter Garland’s works. Here is an excerpt, mm. 19-23 (showing a transition between sections) from the second movement of his piano piece Jornada del Muerto (1987):

The entire movement employs only five chords in the right hand – given only as seen here, mind you, with no transpositions or octave displacements – plus the pitches B, D, and E in the left hand, usually as octaves, and in one section as single notes:

No process or continuity device informs this music; it is entirely and intuitively melodic in conception, if chordal in execution. Yet despite its extreme paucity of material, this lovely five-minute movement goes through seven sections touching on four different textures and rhythmic styles, undulating between two tempos. “I feel influenced,” Peter has said, “by American modernism from the ’20s, not the ’50s and ’60s. My take on modernism goes back to Cowell and Rudhyar.” Point taken: a line can be drawn from Garland’s use of only specific sonorities to the (vastly underrated) piano music of Rudhyar. Nevertheless, the conscious asceticism of his music is a far cry from Rudhyar’s employment of the entire piano as a mammoth sounding board, and it is worth noting that Peter studied at CalArts side by side with two other seminal postminimalists, Guy Klucevsek and John Luther Adams (all with Jim Tenney, who had his own postminimalist streak). In any case, the appearance of Jornada del Muerto in the late ’80s was exactly in keeping with the then-current postminimalist aesthetic. You can hear the second movement here.

Like Duckworth’s, Janice Giteck’s music is widely heterogenous in its sources of inspiration, but each movement blends those sources into a seamless fusion. The fourth movement of her Om Shanti (1986) draws inspiration from Indonesian gamelan music, and its melody, sung wordlessly by the soprano and doubled in various other instruments, runs along a pelog scale, F G B C E:

The piece is pervaded by a single line of 8th-notes running without interruption through the piano left hand and clarinet, all on those five pitches E F G B C, without ever repeating, like an endlessly flowing river that is never the same twice. In addition, the pitch A appears in the voice melody and its doublings, but only in the upper register and at moments of maximum intensity. At various points the melody is punctuated, as shown above, by one or two notes in the upper piano and crotales, always on the ambiguously unresolving pitch F, rendered even more unsettling by a bass note B in the cello (whose C string gets tuned down to B in the third movement, but that’s another story). The movement, which you can hear here, is a masterpiece of intuitive intensification of melody, texture, and even harmony within an invariant limited scale.

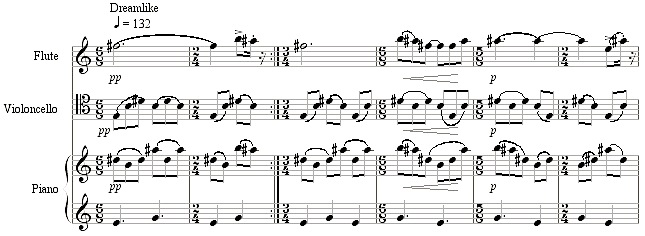

Merely five pitches also suffice for the nine-minute length and formal complexity of Paul Epstein’s Palindrome Variations (1995): G A Bb C D. The most formalist of them all, and a purveyor of note-by-note intricacy, Epstein could be called the Webern or Babbitt of postminimalism, the extremist in search of a purely musical logic. His 1986 Musical Quarterly article “Pattern Structure and Process in Steve Reich’s Piano Phase” gives almost more insight into his own composing impulses than it does into its ostensive topic; he is fascinated by note combinations that result from permutational patterns. All the same, Palindrome Variations is not (as some Epstein pieces are) a work composed by linear process. What’s interesting about Epstein is that the musical units with which he works intuitively are not notes, chords, or even phrases, strictly speaking, but notational units resulting from the interplay of meter and repetition. Here, the 6-beat phrase of the first two measures (repeated in the second one) is rotated within the measure afterward, so that in m. 3 the pattern starts on the third beat, in m. 4 on the fourth, in m. 5 on the sixth, m. 2 on the second, and so on:

Of course, in so uniform a texture, the meter isn’t felt as a unit, and so the effect is a constant unpredictable juggling of the same elements over and over. By a nonlinear process of note substitutions, the texture gradually transforms into a canon in which all instruments are playing the same motive but out of sync; then there are canonic solos for the flute and cello, and with inexplicable logic the piece moves to a conclusion foreshadowed by a dominant preparation and a convincingly logical, almost Bartokian, closing move to unison melody, all without any perceived breaks in Epstein’s tightly wound motivic flow. You can hear all that here. I think of Epstein as music’s answer to an op artist like Bridget Riley, whose superficially strict procedures result in wildly expressive visual surprises; similarly, Epstein’s rigorous attention to geometric detail creates conundrums for the ear. I doubt anyone can deny that, like Babbitt within the 12-tone world, he sets a certain edge beyond which postminimalism can go no further.

The first 25 measures of Belinda Reynolds’s Cover (1996) certainly seem to be those of a postminimalist piece. Again, only six pitches are used – E F# G A# B D# – with E in the piano as a low drone note, and a certain obsessive reiteration of characteristic figures, particularly the competing fifths E-B and D#-A# (repeat sign not in the original, but mm. 3 and 4 are identical to 1 and 2):

However, the music crescendoes to a sudden new chord at m. 26, and subsequently every few measures the music ups the energy by shifting to a new scale. There might be no reason to call this curvaceous, quasi-organic piece postminimalist except that, within each “moment” (to use the Stockhausenesque term), it tends to build up pitch sets and melodies additively, starting as an undulation of two notes and adding in others, almost like a memory of minimalism. Ultimately, Cover‘s form is not postminimalist – there are no more implied limitations on where the music could go than there are in Mozart – but its technique is. One of the advantages of defining postminimalism (or any style) in terms of its central idea is that we can treat the style itself as an ideal form, and talk about degrees to which a particular piece participates in that style. Just as Time Curve Preludes lies slightly on one side of postminimalism, coming from minimalism, Cover is a piece evolving from postminimalism and leaving it behind toward something else, but with its origins still much in evidence. You can hear the entire ten-minute work here.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Now, don’t write in and tell me you don’t like these pieces. Who cares if you like these pieces? Do I care if you like these pieces? Do I, Kyle Gann, personally give a shit whether you like these pieces? No. No, my friend. I do not. What I care about is that you acknowledge that these pieces by different composers with very different creative personalities share several very clear stylistic characteristics – that they, in effect, define a style. What we name that style, I do not care. If everyone wants to call it Charlie, we can call it Charlie. But I have called it postminimalism, because that word was already in use in the early ’80s but floating around loose without any specific definition. (Rob Schwarz applied the word to John Adams and Meredith Monk in his Minimalists book of 1996. But I have trouble finding important differences in method between Meredith and the true minimalists, while composers of the “neoromanticism with minimalist elements” style that Adams represents were vastly outnumbered in the ’80s by the postminimalists who fit my definition. There are many more of them today.) And it is clear that these composers were all reacting to minimalism, but that minimalism was not their only influence. They defined, among them, a soundworld quite different from minimalism, one of brevity rather than attention-challenging length and stasis, one of intuitive lyricism and mysticism rather than obvious structure and worship of “natural” processes.

Nor – to preclude the kind of silly clichés that some composers bring to these discussions – is postminimalism a “club” that anyone ever decided to join. Not one of these composers ever sat down and said, “I’m going to write a postminimalist piece,” and it would be surprising if anyone (aside from myself) ever has. Anyone who thinks there could be a “doctrinaire” postminimalist doesn’t understand. The style is accompanied by no ideology. Nor was postminimalism even a “scene.” Duckworth and Giteck were unaware of each other until I introduced them. I doubt Peter Garland has crossed paths with Belinda Reynolds to this day. Minimalism unleashed a set, or several sets, of potentialities into the ether, and, in the way that great minds so often think alike, several dozen composers pulled new musical solutions out of the air that happened to have a lot in common. The grouping of these composers into a postminimalist style is not a fact of composition, but a fact of musicology. It is the perception of the first person to study all this music – and I have hundreds more examples where these came from, don’t even get me started on my John Luther Adams file – that commonalities among a certain body of pieces constitute a style. That perception will stand (and has already been widely quoted in the literature) until it is replaced by a more compelling perception, as perhaps will happen someday. This remains true even despite the music world’s refusal to deal with this music as a repertoire, after the vogue it enjoyed temporarily among the New Music America crowd in the mid-1980s.

I wonder if that indifference is perhaps due to postminimalism’s generally formalist concerns, its fascination with pattern and texture, at a time when the music world had become totally disenchanted with formalism. The widespread abandonment of serialism around 1988 (the year it seemed to me that disgust with the 12-tone idea reached a tipping point) inspired a near-universal move toward social relevance and widespread appropriation of pop and world-music elements, a conviction that music should refer to the world and not only to its own processes. Totalism, the other big movement that branched off from minimalism, throve much better in the post-serial milieu, as evident in the more visible careers of the Bang on a Can composers. In many respects, postminimalism was an answer to serialism far more than minimalism was. The postminimalists, like the serialists, worked at creating self-sufficient and self-consistent musical languages, in this case a language in which the reduction of musical elements made musical logic apparent. The attitude was almost, “Let’s do formalism over again and get it right this time, not anxious and apocalyptic and opaque like the serialists, but transparent and lyrical and pleasant.”

By 1990, however, formalism of any kind was a hard sell. Justifiably tired of music that begged for technical analysis, the world wanted big, messy Julian Schnabels of music, not clean, pristine Bridget Rileys. It was, and remains, difficult to argue for music so focused on its own musical processes, no matter how pleasant to the ear. In fact, postminimalism’s very pleasantness works against it: in the macho music world that John Zorn ushered in and the faux-blue-collar Bang-on-a-Canners have continued, postminimalism has never seemed kickass enough, its archetypes too feminine and conciliatory. (Kickass, kickass, kickass… I remember with perverse pleasure how ridiculously frequently that word came to everyone’s lips in the New York scene of the late ’80s, as though they had suffered some dire threat to their collective masculinity, and how easy it was to make fun of.) But pendulums swing, fashions change, and at some point the music world will remember that notes themselves can be made into patterns fascinating to listen to for their own sake. When that time arrives, the beautiful, varied, surprising postminimalist repertoire will be here to be rediscovered.

UPDATE: My little tirade above earned me a very funny comparison with Milton Babbitt via Darcy James Argue. Part of what’s funny is that the Babbitt paragraph he quotes is one I happen to have always agreed with. Babbitt’s a smart man, and not wrong all the time.