From Hits to Niches

When I was asked to come up for this conference on “New Music and the Media,” I tried for weeks to think what new music and the media could possibly have to do with each other aside from both being eight letter phrases in which the second word begins with M. But then I talked to Tim Brady, who made me realize that my thinking had been very pre-9/11, as they say, and that I had been limiting the media to what we now universally refer to as the MSM, or the “mainstream media,” which of course doesn’t cover new music to any appreciable extent.

As a new-music critic for the Village Voice newspaper for 19 years, I used to be a representative of what we might now laughingly refer to as the AMSM, or possibly altMSM – the “alternative mainstream media.” Laughingly, because now that the Village Voice has been bought by the huge corporation New Times Media, it has become one of 17 so-called “alternative papers” across the U.S. run by a large conglomerate that saves money by running the same film reviews in all those papers. Which means that the difference between the altMSM and the MSM now runs about as deep as the difference between unscented Ivory soap and regular scent Ivory soap.

Declining to join the new, more corporate altMSM, I graduated instead to the Blogosphere, where the media – by which I suppose I would include music blogs and classical music web sites – does cover new music, and quite extensively. As a member of the altMSM, I used to be an expert. I knew what went on in the Village Voice offices, and you didn’t. I knew what the paper’s editorial policies were, and you didn’t. As a citizen of the Blogosphere, on the other hand, I am not an expert, or rather, I am as much of an expert as most of you are, and no more. The blogs I read you can also read. The information I have access to on the internet, you also have access to. I can’t even tell you how to set up your own blog, because my blog was set up for me by ArtsJournal.com, so if you’ve started your own blog, you know more about blogging than I do.

Journalist Gary Kamiya at Salon.com wrote an article last week about the experience of having hundreds of people posting comments, many of them critical and even vituperative, after every article he wrote. One of the comments posted in reply suggested that, from now on, writers need to adopt a more humble and conversational tone, because we no longer speak ex cathedra to a faceless audience that can’t speak back. So it seems to be a symptom of our recent intellectual climate change that I give this keynote address not because I am an expert on new music and the current configuration of media, but simply because I was the one of us who was asked to speak for the crowd. I will attempt to keep my remarks humble and conversational. I am going to try to put some ideas in order, but I rather despair of telling you anything most of you don’t already know. The cultural paradigm to which we have recently switched is too new to be tremendously complicated yet, and one gets the sense that everyone has followed along so far. Culturally, and at least for the moment, the internet seems to have brought us all on the same page. In fact, the fact that you can’t all immediately post comments disagreeing with me after I finish speaking today fills me with a certain sense of nostalgia.

So one of the effects of our climate change is to call into question the notion of expertise. Bob Christgau, dean of rock critics, who was recently fired from the Village Voice by the conglomerate that bought it for the crime of having too high a salary, wrote recently that newspaper criticism is dying because people have too many other places to go for recommendations, and no longer need to read the experts. For every compact disc you consider buying, you can look on the relevant page at Amazon.com and read reviews by people who have presumably have heard, or possibly haven’t heard, the disc – for instance, if you look at my last CD there are two reviews that so misdescribe the music that they obviously didn’t bother listening – and then those reviews are reviewed by the people who read them. The old saying “Everybody’s a critic” is now literally true. Even publicly, judgment is no longer a specialized function.

But I have learned recently that in losing my privileged status as an expert, I have not merely receded into the great undifferentiated stream of humanity. Oh no. For awhile I was a “content provider,” which I rather liked because it made me sound so – contented. As it turns out, though, I am not merely a content provider, that is, one who exudes words and images to fill a space between advertisements. As a content provider known for particularly precise recommendations, I am also a filter in the navigation layer. (I just found this out a few days ago. I feel like the prince in the film The Madness of King George who learns that he is also Bishop of Osnabrück, and comments, “It’s amazing what one is, really.”) You can’t simply alphabetize all of the recordings that have ever been made and let people sift through them looking for something that might appeal to them. People who are looking for someone who sounds like Norah Jones would end up accidentally having to listen to my music, and become terribly perplexed. So the sea of digital music has a navigation layer: a network of links from one piece to another and one type of music to another, so that, given one recording you like, you will soon be reeled into the niches in which you feel at home.

The components of that navigation layer are filters, both mechanical and human. You’ve all seen the mechanical filters at work. If you recently bought a DVD of Sir Laurence Olivier’s Henvy V on Amazon, the next time Amazon might suggest that you will also enjoy the films Regarding Henry, Henry and June, and Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer. Most people already tend to prefer human filters, I think, which are more intelligently contextual and efficient. To be a good filter does not require, as being a good newspaper critic did, being a good writer, nor does it require intelligence or even taste (one could be a filter, after all, of Gilligan’s Island episodes). What it does require is voluminous access to a certain niche literature and some degree of organization. In these areas I am exemplary. My access to postminimalist music of the 1980s and ’90s is unparalleled. That is my niche, and almost no one cometh to that niche except through me.

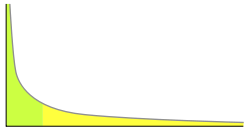

It’s one of the smallest niches on the internet, but that doesn’t matter anymore. For to be a filter is to be a guide into what is now called the Long Tail. The term originated in a 2004 article, later turned into a best-selling book, by Wired magazine editor Chris Anderson. (I apologize to all of you who already know all about the Long Tail, but I will be as humble and conversational in describing it as I can.)  The idea is that if you rank any phenomenon according to frequency, such as book or record or beer sales, you get a distribution graph with a vertical part that curves into a horizontal part. For instance – and I take this example from Wikipedia –

The idea is that if you rank any phenomenon according to frequency, such as book or record or beer sales, you get a distribution graph with a vertical part that curves into a horizontal part. For instance – and I take this example from Wikipedia –

in standard English, the word the is the most common word… about 12% of all words in a given text are the, while [the word] barracks occurs in less than 1 out of 60,000 words, but cumulatively, words roughly as rare as barracks make up about a third of all text.

So occurences of the word the would register way up at the top part of the graph, while occurrences of barracks would be way down in the long tail. But while instances of the vastly outnumber instances of barracks, rare words down in the Long Tail make up almost as much of our written language as common words like the.

The application to music, I think, is pretty obvious. The other day when I was writing this, the number one top-selling artist on Amazon was Norah Jones. My latest CD came in at number 234,754. However, in terms of sales there are thousands of times as many Kyle Ganns, as many artists who sell only a few hundred CDs, as there are Norah Joneses who sell hundreds of thousands of CDs, to the extent that the thousand least-known composers represented on Amazon may altogether sell as many or more CDs as Norah Jones does by herself. Therefore, if you have a brick-and-mortar store with only room to offer a hundred CDs, you will of course want to sell Norah Jones rather than Kyle Gann, but you will miss out on the equal sales you could be making from the thousands of artists whose CDs only sell a few copies each. This is where the internet comes in, because, not having storage issues, it can offer both Norah Jones and Kyle Gann and his myriad ilk. You walk the streets of Winnipeg trying out record stores, and you’ll have a complete Norah Jones collection several times over before you find a Kyle Gann CD. But you go to Amazon and type in “Norah Jones” and “Kyle Gann,” and either name comes up just as fast as the other.

Chris Anderson talks about how the era of “hits,” of blockbusters, is over, giving way to the era of niches. Pardon me if you’ve already read this on the internet, but I’ll quote at some length what he says in elaboration:

Most of the top fifty best-selling albums of all time were recorded in the seventies and eighties… and none of them were made in the past five years…

Every year network TV loses more of its audience to hundreds of niche cable channels… The ratings of top TV shows have been falling for decades, and the number one show today wouldn’t have made the top ten in 1970.

In short, although we still obsess over hits, they are not quite the economic force they once were. Where are those fickle consumers going instead? No single place. They are scattered to the winds as markets fragment into countless niches.

The great thing about broadcast is that it can bring one show to millions of people with unmatched efficiency. But it can’t do the opposite – bring a million shows to one person each. Yet that is exactly what the Internet does so well.

He describes talking to a Mr. Vann-Adibé who engineered an internet jukebox, and says,

During the course of our conversation, Vann-Adibé asked me to guess what percentage of the 10,000 albums available on the jukeboxes sold at least one track per quarter…

The normal answer would be 20 percent because of the 80/20 rule, which experience tells us applies practically everywhere. That is: 20 percent of products account for 80 percent of sales (and usually 100 percent of the profits).

…Half of the top 10,000 books in a typical bookstore don’t sell once a quarter. Half of the top 10,000 CDs at Wal-Mart don’t sell once a quarter…

So Anderson guessed 50 percent. The correct answer was 98 percent. That is, 98 percent of the tracks on the jukebox sold at least once per quarter. Doing research, he found that this 98 percent was pretty much a rule: whenever an internet company made a vast quantity of selections equally available on the internet, 98 percent of the products showed evidence of some demand every quarter. And he goes on:

…As the company added more titles to its collections, far beyond the inventory of most record stores and into the world of niches and subcultures, they continued to sell. And the more the company added, the more they sold.

Each company was impressed by the demand they were seeing in categories that had been previously dismissed as beneath the economic fringe… For the first time, I was looking at the true shape of demand in our culture, unfiltered by the economics of scarcity.

This description accords perfectly with my experience. I go around lecturing on new music and playing it for audiences, and everywhere I go, I find and create demand for new music. People come up to me afterward and ask, “That music was fantastic, where can I find it?” I run an internet radio station for new music, and people write to tell me all the time about the wonderful composers they discovered listening to PostClassic Radio. And then, on the other hand, I talk to publishers about books I want to write, and exactly as Anderson says, they invariably dismiss the music I’m a filter for as “beneath the economic fringe.” They say, “Oh, we can’t publish a book about that music, there’s no interest in it.” And newspaper editors tell me, “Oh, we wouldn’t run a story about that music, there’s no interest in it.” For 25 years I’ve been shuttling back and forth between two realities, one in which there’s patently plenty of demand for new music, and another in which there is confidently asserted to be no demand whatever.

The concept of the Long Tail now gives me a way to make sense of my experience. The book publishers, the newspapers, the radio stations, the record stores, are caretakers of the vertical part of the graph. They all make a living by finding out what items will be bought or appreciated by the largest number of people and offering only that. And for 25 years I’ve been a Chicken Little alarming people because that vertical stack of hits has gotten thinner and thinner and thinner, and more and more difficult to get one’s music into.

When I was young, the best new music was on big, well-known labels like Columbia and Deutsche Grammophon. By 1980, those labels had abandoned new music, which was now on prestigious specialty labels like Lovely Music and New Albion. By 1990, the music I was most interested in writing about for the Voice was now on even smaller labels, rarely available in stores, like Mode and Artifact and Cuneiform. And by 2003, the music I most wanted to put on my radio station was at best on tiny labels run by the composer, like Mikel Rouse’s Exit Music or Bang on a Can’s Canteloupe, and more not even commercially recorded at all, just sent to me, or uploaded to the internet, by the composer. More and more and more of the Long Tail was abandoned by the industry that used to bring new music to the public and keep it alive.

And so it was at every level. The New York Times cut back its arts coverage by 25 percent, and the Village Voice made fun of them. The next month, the Village Voice cut back its arts coverage by 25 percent, and later both papers cut back still further. More and more, newspapers cover only the organizations that give them advertising revenue. The classical musical organizations who most reliably advertise in newspapers are the local orchestras. And so composers whose music gets played by orchestras have always had the most chance of getting publicity; by the 1990s, it seemed like they were the only composers getting publicity. If your music isn’t played by orchestras, your chances of getting into the prestigious vertical shaft of the distribution graph covered by the MSM is just about nil.

For 20 years I’ve been kind of a professional pain-in-the-neck at music conferences, expounding a gloom-and-doom scenario based on the shrinking vertical part of the graph. What my congenital pessimism kept me from noticing was that, as the vertical part was thinning, a lot of institutional sand was running down into the Long Tail. As I read about new music on the internet, I see very different names than I’m accustomed to reading about in newspapers and music magazines. Composers with strong cult followings like Charlemagne Palestine, Brian Ferneyhough, and Phill Niblock get discussed far more often on the internet than they ever did in print. A lot of what we think of as successful establishment composers are nearly absent from the internet. Look up Milton Babbitt or Jacob Druckman, and you may not find much more than music publishers’ blurbs, which are notoriously one-dimensional. But look up La Monte Young, or Kaikhosru Sorabji, or Claude Vivier, or the San Francisco composer Erling Wold, and you can find tons of information: scores, analyses, discussion groups, great Wikipedia articles.

Hundreds of scholars squeezed out of the vertical shaft by commercial pressures have emigrated to the internet. One of the first big composer web sites I saw in the ’90s was a scholarly site for the Russian composer Cesar Cui; I’m sure its author was ready to write a book about him and was discouraged by publishers, and so blossomed onto the internet. In its discussion of subjects conventionally covered by print encyclopedias, Wikipedia leaves a lot to be desired. But its superiority to any print medium in the coverage of new musical genres and artists not found in dictionaries but nevertheless loved by thousands of people is absolutely phenomenal.

And given my experience hawking new music around the country and in Europe, I get a strong impression that the musical interest I see on the internet is closer to, as Anderson says, “the true shape of demand in our culture, unfiltered by the economics of scarcity.” It starts to look to me like the classical music culture whose deterioration we’re so panicked about, with its star system, its exclusive character, its timidity in the face of public opinion, its assumptions of economic scarcity, its conviction that you have to choose between me and Norah Jones and there’s no room for both, was a neurotic, unreal system whose true purpose was never to disseminate culture, but to make money for the people in power. And what we see on the internet, flawed as it may be (and I’ll get to some of its flaws in a moment), is more the result of true enthusiasm expressed by people who have nothing to gain and no reason to say anything but the truth.

Everyone who’s sat on grant and award panels knows that often the piece of music that wins is not the one any panelist feels most strongly about, but the one that is the least offensive, that no one particularly objects to. Likewise, I think that for similar reasons of scarcity and the kind of concensus needed, our old musical life created a culture in which the music that aroused the greatest passions often got pushed out into the long tail. As Anderson says, “For too long we’ve been suffering the tyranny of lowest-common denominator fare, subjected to brain-dead summer blockbusters and manufactured pop.” It seems to me that this is just as true in classical new music as it is anywhere else. Newspapers, book publishers, music publishers, orchestras, radio stations, all the various MSM outlets, and even television have a lot to learn from what goes on on the internet: which artists inspire heated discussion groups, which ones merit lengthy articles on Wikipedia, which ones amateur scholars furiously debate each other about. The internet, especially now while hardly anyone makes any money contributing to it, more immediately reflects which music inspires true devotion.

And though the artists best represented there may still seem commercially unfeasible now, the internet’s ability to access the rare music of the Long Tail is bound to bring more and more listeners in that direction. Anderson’s graphs show that not only does the vertical “hits” part of the distribution curve get thinner, its peaks fall lower, while the Long Tail becomes thicker as more customers discover it. How far the internet can change the landscape might be indicated by the fact that my blog was recently ranked as the number five most influential classical music blog – and we’re talking about a blog whose idea of a big-name classical composer is Rhys Chatham. As Anderson writes about the ongoing collapse of the record business:

[T]echnology… offered massive, unprecedented choice in terms of what [people] could hear. The average file-trading network has more music than any music store. Given that choice, music fans took it. Today, not only have listeners stopped buying as many CDs, they’re also losing their taste for the blockbuster hits that used to make them throng those stores on release day. Given the option to pick a boy band or find something new, more and more people are opting for exploration, and are typically more satisfied with what they find. [p. 33]

As they wander farther from the beaten path, they discover their taste is not as mainstream as they thought (or as they had been led to believe by marketing, a hit-centric culture, and simply a lack of alternatives). [p.16]

[A]s… companies offered more and more… they found that demand actually followed supply. The act of vastly increasing choice seemed to unlock demand for that choice. [p.24]

“More and more people are opting for exploration.” I don’t remember the 20th century very well, but I do seem to recall that that what 20th-century composers used to dream about most was that, someday, more and more people would opt for exploration. All my life I’ve lived in the Long Tail, without exactly recognizing that’s where I was. And it turns out they decided to build the information superhighway right through the middle of it. (I can imagine how excited Canadian composers are by this news, since they evidently see their entire music scene as inhabiting the Long Tail.)

And so, very recently, the internet has been turning me from a pessimist into an optimist. Of course, our global climate change is submerging tropical islands, while turning some frigid wastelands into new tropical paradises. Likewise, our intellectual climate change will doubtless destroy as well as create. Some things are bound to be lost, and we don’t know yet what will replace them. One thing that’s been lost, most notably, is the ancient practice of getting paid. Most of the work I do on the internet I do without compensation, and no one’s quite figured out what to do about that yet.

Secondly, I have trouble seeing what’s going to replace editing. Back in my old ex cathedra days, I used to spend 90 minutes a week going over my Village Voice column with a brilliant editor, Doug Simmons, who had studied classical rhetoric in college. Of course, I was being edited for the arrogant, magisterial idiom, but some of that training still carries over into the humble, conversational style I am careful to use today. As I look through internet discourse, much of the writing I read, even when it reveals taste and intelligence, falls into clichés, common syllogisms, academic obfuscation, and a general lack of specificity and clarity. My own apprenticeship in this area was arduous if exhilarating, and took seven years, and I don’t see where the pressure to improve the level of the discourse is going to come from.

There’s an analogy I often take from the field of piano tuning. Piano tuners tell me that if you know how to tune pianos traditionally, then the new electronic tuning machines make it easier; but that if you can’t do it traditionally, and start out relying on the electronic tuner, your pianos will never stay in tune for very long. I sometimes apply this to composition: that if you know how to compose on paper with a pencil, you can make the transition to composing directly in music software, but that if you don’t, you’ll always have issues with continuity and timbre. Some poets say something similar about writing poetry on a word processor. And it may apply to many other transitions to digital technology.

One change I haven’t figured out yet is who my new audience is. Going from the altMSM to the blogosphere created an illusion that I was addressing a vastly larger crowd. My statistics page tells me that 55 percent of my readership is in the East Coast time zone, 10 percent on the West Coast, 12 or 15 percent in Western Europe, and now and then 1 or 2 percent in the time zones that include India or Australia. My blog can be read from anywhere in the world, which gives me a heady feeling of addressing the planet.

At the same time, I notice that I get comments mostly from the same 75 or 100 people who leave comments at New Music Box and Sequenza 21, and that they all seem to be composers. When I wrote for the Voice, anyone who wanted to read the political news or the pop record reviews, or look through the sex ads, at least had my column under their arm, and was likely to flip past it, perhaps notice it. Now it seems that I am read by a small, if widely dispersed, crowd of internet-obsessed composers who all frequent the same web sites and comment on each other’s blogs. A lot of the work I have always done has been advocacy for composers, and it makes no sense to advocate composers to other composers. It seems to primarily piss off the composers you’re not doing advocacy for. Advocacy for composers only works when directed to the music-loving public, or to power-brokers who arrange performances and recordings, and we composers are all reading each other. Ironically, our ability to reach out to the entire world may have led, for now, to a kind of hermetic professional parochialism.

How these issues will work themselves out, we don’t know yet. It’s difficult to give a keynote address in the dead center of a large cultural transition, especially one that has done away with the concept of expertise. But all that’s speaking as a writer, as a former expert, as a filter on the navigation layer. Speaking as a composer, I used to despair that the older I got, the more the traditional needs of the composer – publication, performance, recording, distribution, publicity – seemed to be becoming more and more elusive. But now that the internet has ushered the world into the Long Tail, it’s not so lonely down here anymore, and I’ve come to feel optimistic. I now trust that some 98 percent of you will share my optimism – at least once a quarter.