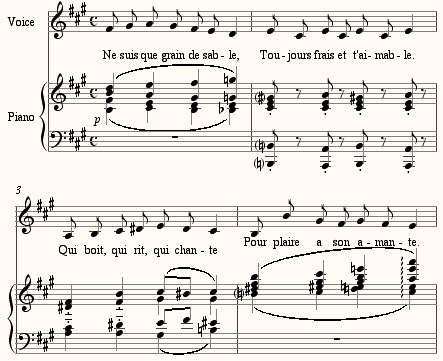

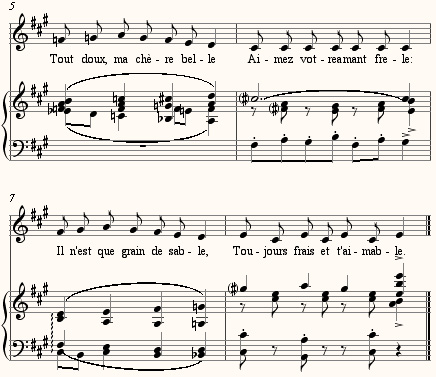

Ninety-two years ago this week, between Nov. 20 and Dec. 2, 1914, Erik Satie penned Trois Poèmes d’Amour, a trio of brief love songs to poems of his own. At the risk of taxing my reader’s browser, I offer the first here in its entirety:

One notices right away that the voice sings the same rhythm in all eight measures: six 8th-notes and a quarter-note. This is also true of the other two songs: not only that they use the same rhythm in all eight measures, but that they all use this particular rhythm, six 8th-notes and a quarter-note. Thus not only did Satie write three songs each devoid of rhythmic variety, he wrote three songs with no rhythmic variety among them (save for some peculiar chromatic grace notes in the piano in the third, which the sketches indicate were added as an afterthought just before publication). You can listen to the whole set, which lasts barely two minutes, here, on an old Angel vinyl record with baritone Gabriel Bacquier and pianist Aldo Ciccolini. Rather than a collection of three songs, it is really one song – written three times. And yet, no one of the songs is superior to the others, no one sounds like the authentic model from which the other two were derived. Each has its own slightly distinct atmosphere. Each song is memorable on its own; each could stand on its own. Were you to insert a measure from one song into another, those of us familiar with the songs would find the intrusion jarring.

Since my teenage years I have been mesmerized by the studied blankness of mind that could produce these songs. To write a song, and then, as though you had never written it, to write another with the same rhythm and chordal characteristics, just as fresh, just as authentic, requires a mind that can wipe out the immediate past and return to center. And then, within that song, to write each measure so unmindful of its predecessor that you feel no need for contrast, yet that you can also repeat with no fear of exact repetition, seems like the kind of acute moment-to-moment awareness that Zen masters describe. In the poems, Satie was mimicking the flat rhyme-scheme of 12th-century trouveres. But, lest you conclude that only the texts made this feat possible, remember Satie’s similar achievements in formal identity in the far more ambitious contexts of instrumental works: not only the famous Gymnopedies and Sarabandes, but the even more astonishing Pièces Froides and Nocturnes, and to a lesser extent the Gnossiennes. He is capable of writing a third movement virtually identical to the first, or one that quotes the first as though it is not a quotation, but a new creative odyssey leading back into identical material. Like Borges’ hero who writes (not rewrites) Cervantes’ Don Quixote, Satie was capable of writing the same music twice: not in absent-minded forgetfulness, but in acute awareness of every moment as new.

Having discovered Satie at 15 and instantly recognized him as an old friend, I am more and more trying to achieve the blankness of mind – and also the craft, because contrary to public impression, Satie was a painstaking reviser – that makes pieces like Trois Poèmes d’Amour possible. “What should I do in this section?” is a question I try to prevent from ever arising. By the end of the first measure, everything should be decided, and the only task is to continue. By continue I mean simply to sustain the idea, to keep it alive without having to resort to anything else. Although, it’s hardly simple, it’s damned difficult: so much easier to move to a contrasting section, to bring in a second idea, to swerve and create a facile “unity” by returning to the original material later. This is what La Monte Young meant, I surmise, when I asked him circa 1991 why the five movements of his early string quartet were so similar, and he replied, after a moment’s thought, “Contrast is for people who can’t write music” – an unnecessarily dismissive formulation, perhaps, but one I found inspiring. And possibly what Kierkegaard meant when he titled one of his books, “Purity of Heart Is to Will One Thing.”

The classical music world – which values educatedness in a composer over discipline of will, and speciously takes variety of techniques as evidence of education – does not much respect this goal, nor Satie. But that’s the goal that continues to inspire me. (One piece that achieves it heartbreakingly well is Evensongs by Ingram Marshall, which I have just added to Postclassical Radio.)