Today in three hours I finally finished my setting of E.E. Cummings’ My father moved through dooms of love, in which James Bagwell will conduct the Dessoff Choir on March 10. I had quit working on the piece in July because I hit a snag. The setting of the following words just wasn’t right, and so the accompaniment (for piano and violin) wouldn’t write itself, and I knew it was because I didn’t really understand them:

then let men kill which cannot share,

let blood and flesh be mud and mire,

scheming imagine, passion willed,

freedom a drug that’s bought and soldgiving to steal and cruel kind,

a heart to fear, to doubt a mind,

to differ a disease of same,

conform the pinnacle of am

(You may think me foolish for finding this difficult, but outside my field I’m not very bright about a lot of things.) Looking at it fresh after four months’ hiatus, I suddenly realized that in “to differ a disease of same” the “same” refers to “mind” in the previous line, and that I needed to separate out the phrase “to differ” as the subject of the rest of the line. Cummings is describing how adept his late father was at negotiating a world in which men kill out of selfishness, in which imagination is turned to the service of schemes, in which to differ is considered a disease of the mind, and to conform is considered the pinnacle of being: a world not unlike the one I live in. “If every friend became his foe,” he says of his father, “he’d laugh and build a world with snow.”

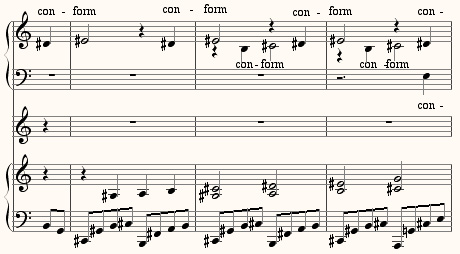

Not having understood this clearly, I had set the words too quickly, relying on only their rhythm. The passage was merely transitional. A “merely transitional” passage is a flaw: every moment of a work has to show the same intensity of care and focus, has to bring its own delight to the listener. So now I set off the words “to differ,” and when I got to the word “conform,” I counterintuitively brought the music to a halt, repeating it over and over, adding five new measures in the process. “Conform” is what I consider the ugliest word in the English language, the most evil, most heinous word ever devised. It flashes at us from every billboard, is the surreptitious motto of every institute of higher learning, is the directive underlying every newspaper review, the unspoken impetus behind every rejection, the veiled urging behind every advertisement. Hardly can one turn anywhere without hearing the world shout “conform!” If you will behave and be one of the good Stepford composers, your orchestra pieces will be celebrated by the bigshots. If you will join the Stepford professors, the administration will shower favors on you. If you will only conform, the powers that be will welcome you into their lower ranks – pending continued good behavior, of course. “The virtue in most request,” wrote Emerson, “is conformity.”

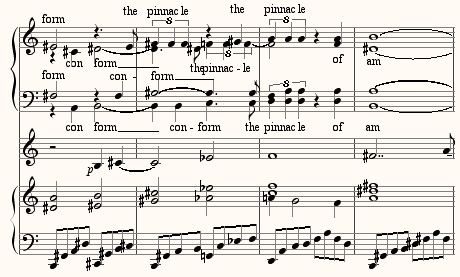

And so what I had missed was that Cummings was offering me an opportunity for supreme irony. Over soothing, undulating chords I reiterated “conform, conform, conform” in dulcet and seductive tones, just like the world does. Suddenly, instead of an undistinctive transitional passage, this became (as I had inchoately sensed it would) the emotional center of the piece, a serenely damning indictment of the world that one nearly has to have a nonconformist streak to appreciate:

You’ll note that “the pinnacle of am” only rises to a medium-range B – not a very high pinnacle.

Cummings wrote the poem in 1926, after his father was killed by having his car hit by a train. My father died last April – I had begun writing the piece in anticipation – and Maestro James Bagwell had lost his father the year before. The piece is dedicated to James, in the solidarity of grief.