I don’t understand why the electric guitar orchestra hasn’t become a compositional focus for more composers, for practical reasons alone. It certainly looked like it was going to in the 1980s, with works and ensembles by Rhys Chatham, Glenn Branca, John Myers, Wharton Tiers, Phil Kline, and Todd Levin. The old joke is,

Q.: How do you get a guitarist to stop playing?

A.: Put some sheet music in front of him.

and certainly dealing with guitarists who don’t read was part of the challenge, especially starting in 1989 when Rhys Chatham initiated the 100-guitar tradition with An Angel Moves Too Fast to See, premiered in Lille, France. “Guitarists who can’t read can at least count,†Rhys liked to say, and this insight led the guitar-orchestra genre into totalist territory, however inadvertently. Glenn Branca couldn’t read music himself until he had finished several guitar symphonies, and at least his Sixth Symphony (also 1989), notated on graph paper, has rhythmic grids showing some players how to change chords every four beats while others are changing every five beats and still others every six. His 1994 Tenth Symphony for nine guitars, more normally notated, contains at one point an approximated Nancarrovian tempo canon at tempos of 7:8:12.

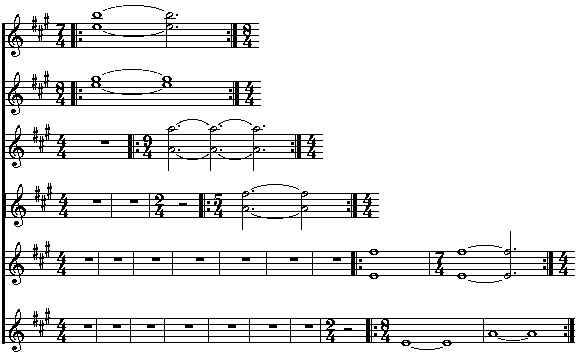

In An Angel Moves Too Fast to See Chatham solved the reading problem by dividing his 100 guitarists into an inner and outer circle, with the musically literate in the inner circle. In the fifth movement (he now calls the piece his First Symphony, though I think he avoided that at the time because Branca was for some reason being criticized for calling his pieces symphonies), he divided the orchestra into six rhythmic layers, each repeating a chord or phrase at diverse regular intervals (monomial or binomial periodicities). As you can see in the example below, one rung of guitarists played E and B every 7 beats; another E and G# every 8 beats; another an octave A every 9 beats; another, after a pause, A and F# every 5 beats, and then two more groups on longer patterns:

Put them all together, and the following process-generated melody is clearly audible:

What you can’t get from the recording (excerpted here, and available on Table of the Elements) is the totally original correlation of space and pitch that resulted. (I just missed the Lille performance by hours, but heard the North American premiere in Montreal.) A hundred guitarists, each with an amplifier and enough room to swing around and look cool, take up a tremendous amount of space; and since each group was herded together, the E-B chord might come from the middle, while the A-F# came from 60 feet away on the left, and the G# an equal distance on the right. Note by note, the melody bounced over wide distances as though the audience members were ants sitting in the middle of an enormous keyboard. Listening was like watching an arrhythmic tennis game.

This is not new information, by the way; it’s all in my book American Music in the 20th Century. Now that Branca is gathering 100 guitarists to reprise his 13th Symphony in Los Angeles, it may be worth recirculating at the moment.

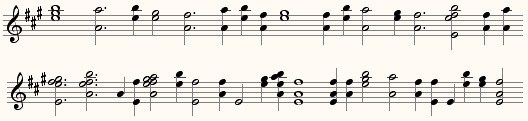

At about the same time I was experimenting with a similar process to generate textures in a considerably more modest setting. My Windows to Infinity for piano (1987) was a reflection on Nietzsche’s concept of the eternal recurrence. I had been amused to read philosopher Arthur Danto parse out the statistical likelihood of eternal recurrance in his book on Nietzsche, and in response wrote a piano piece stretching out to infinity, tracking a recurring combination of notes as it gathered coincidences through millions of repetitions. As you can see below, there’s a middle D# every 5 8th-notes, a middle C# every 7 8th-notes, a lower F# every 29 16th-notes, and so on up through four-digit primes. Every phrase comes back to the C#-D#-E-G# “theme†found in the 4th and 5th measures (a motif also used in my two-piano piece Long Night):

In theory, this nine-minute piece would eventually repeat itself if extended for thousands of years. No one’s ever played the piece but me, and as I’m not terribly satisfied with my one recording, I think I won’t post it here. I used a similar technique soon after in the first movement of Cyclic Aphorisms for violin and piano. I’m sure others have stumbled across this interference of pitch-periodicities concept, but I don’t know of any examples of such an atomistic totalist technique past 1989. It may be worth noting that Nancarrow used the interference of much longer, more complex periodicities in his Study No. 9, way back in the 1950s.