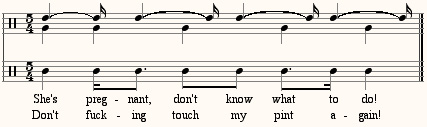

The rhythm in question, perhaps totalism’s second-favorite rhythm after 8-against-9, is an interference of two periodicities, one five units long against another 4 units long. It is given here with its standard American mnemonic device, and also with the one I learned in England:

Several of Mikel Rouse’s pieces for his totalist rock quartet Broken Consort from the mid-1980s revolved around this rhythm. One that did so entirely was High Frontier. In High Frontier Mikel applied a Schillinger technique to this rhythm that was interestingly close to one of Stravinsky’s 12-tone usages. Stravinsky would sometimes rotate through the 12-tone row, moving the first note to the end of the row and then the second note, and so on; likewise, Mikel would take two notes off the front of the rhythm and place them at the end, then do the same with the next two notes, and so on, resulting in the following rhythmic patterns:

Every rhythm in High Frontier, except for the steady 8th-note pattern in the keyboard and drums, is either one of these rhythms or a 2X or 4X augmentation of it. Through these he runs a permutation pattern of six pitches: low F, A-flat, B-flat, B, D-flat, and high F. As I once wrote about the work,

High Frontier sometimes sounds like it is in 5/4 meter, at other times like 4/4 with quintuplets; at other times the listener can perceptually move back and forth at will between these meters, as in an optical illusion. The various rhythms are predetermined numerically to support each other; a slower-rhythm bass line, for example, may coincide with a quicker saxophone melody on every fifth beat, outlining a subtle secondary accent. The surface of Rouse’s music is lively and varied, while the background exerts a consistent, unifying structural influence. The listener can rarely identify by ear what process is going on, but gets a strong sense of an unfolding, internal logic. [“Downtown Beats for the 1990s: Rhys Chatham, Mikel Rouse, Michael Gordon, Larry Polansky, Ben Neill,†in Contemporary Music Review, 1994]

You can listen to High Frontier here.

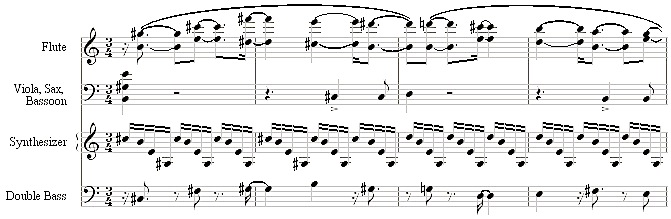

In my own music based on moving among various pulses, inspired by Hopi and Pueblo rhythms, I often used a quarter-note tied to a 16th as a basic pulse, along with quarter-notes, dotted 8ths, and so on. In “Venus†(1994) from my multi-movement work The Planets, I decided to divide the ensemble in half, one half playing a 5/16ths pulse against the others playing a quarter-note pulse – much like the middle movement of Ives’s Three Places in New England, only 5:4 instead of 4:3. “Venus,†couched in 3/4 meter with a running 16th-note arpeggio in the synthesizer, is filled with durations and phrase lengths of five 16th-notes, five 8th-notes, and/or five quarter-notes. These durations pile up subtly in the beginning, and then when the main theme begins, the eight-member ensemble begins to split in two, the synthesizer and lower winds marking the 3/4 meter as the flute, oboe, and bass play a beat only 4/5 as fast:

The theme, moreover, is in five-beat groupings, a kind of virtual 5/4 meter that imposes a 25/16 meter over the notated 3/4 meter. As the two tempos thicken and continue, it can be difficult, as in High Frontier, to tell whether you’re listening to 3/4 with a 5/16 beat superimposed over it, or 5/4 with quintuplets. At the end of the piece, however, the four and five trade roles, so that the woodwinds are now playing the quarter-notes, and the synth is grouping 16th-notes into fives:

You can hear “Venus,†from The Planets, here, played by the Relache ensemble.

Both of these pieces represent totalism’s earlier, “heroic” phase, in which we were willing to go to great lengths of ensemble difficulty to achieve sonic illusions from polyrhythms. The next two works, though, relax into a milder polyrhythmic usage.

Rouse’s 1995 opera Failing Kansas, based on the murders of Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood, returned to the 4-against-5 rhythm on a less virtuosic level. A five-beat isorhythm, divided 3+3+1+3 in 8th-notes, is a recurring idea in the work:

![]()

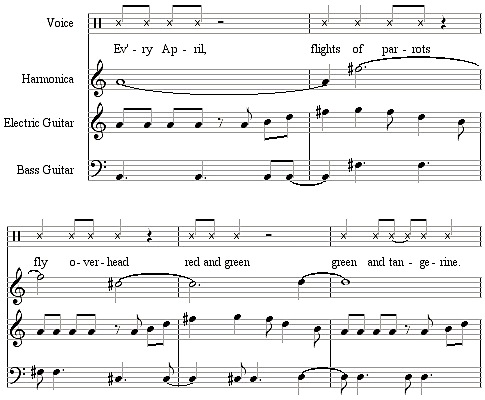

The middle of the second scene, “The Last to See Them Alive,†is based on five- and ten-beat cycles over which a more “normal-sounding†4/4 sometimes asserts itself. The effect is less illusionistic than in High Frontier, but you still have a continual choice as to which meter to tap your foot to (notice the 5/4 ostinato in the bass, reinforced by the harmonica):

You can listen to the two-and-a-half minute excerpt of Failing Kansas that illustrates this tempo effect here. Or, you can listen to the entire ten-minute scene, “The Last to See Them Alive,†here. If you listen to the whole scene, you’ll hear a different, equally elegant effect at the beginning. The opening lyrics are from a hymn favored by Perry Smith, one of the murderers:

I come to the garden alone

Where the dew is still on the roses

And the voice I hear

Falling on my ear

The Son of God discloses

This hymn is in 12/8 meter and spoken that way, though the instrumental music is in 4/4 (the 8th-note equal between the two), creating a subtle out-of-phase relationship of 3+3+3+3 against 3+3+2 patterns. It’s so simple one could easily miss it – in 1995 it took me several listenings to analyze why the rhythm of this passage is so charmingly off-kilter.

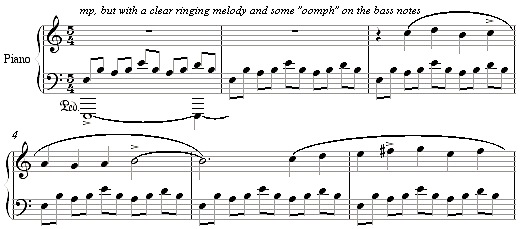

Several years later, in 2004, I came back to the 5:4 idea in the “Saintly†dance for the Private Dances I wrote for pianist Sarah Cahill. Since one player needed to play both rhythms, this was a simple matter of placing 4/4 phrases (marked with accents only for illustration) above a 5/4 ostinato:

You can listen to “Saintly†here. Once again, at the end, I couldn’t resist switching the rhythmic roles as I had in “Venus,” changing to a 4/4 ostinato in the left hand with five-beat phrases in the right.

And, as a bonus track, here’s a four-minute percussion work by John Luther Adams, Always Coming Home, which will give you your fill of five-against-four tempos if you hadn’t had it already. It’s from a larger work called Coyote Builds North America, from 1990, the great heyday of 5:4.