Composer Art Jarvinen, known as “the West-Coast totalist†(poor guy, he never got to come to any of the parties), writes to remind me, in detailing qualities of totalist music, that there was a characteristic totalist instrumentation as well as rhythmic style:

For totalist music to really work requires an edge. A lot of totalist composers have guitar or saxophone or electric keyboards (Rhodes, Hammond, Mini-Moog), or drum set, as their main instrument. I wrote for chromatic harmonica and baritone sax. I don’t want to hear a totalist piece for the Berlin Philharmonic, I want to hear Icebreaker, or the Berlin Phil-Harmonica Band! That’s why the Bang on a Can All Stars have an electric guitar. And Evan Ziporyn plays bass clarinet as if it were a Stratocaster! My totalist rhythmic/contrapuntal ideas and techniques might work with a string quartet, more or less. But my “totalist” pieces, if we are to call them that, work best with more vernacular (less standard/classical) instrumental combinations, that provide a certain edge not available in the standard instrumental groupings that are all about blend and balance. Balance? That’s why we have a guy at the mixing board!

When we recorded [Art’s piece] Clean Your Gun, I could hardly get the engineer to do what I wanted, which was, run the harmonica, cello, violin, and baritone sax through guitar amps, crank ’em up, and mic the amps. He didn’t want to do it, even though I was paying him to. I had to tell him, it’s my piece, we’re going to take a bit of paint off the walls, and you just get it on tape! There is a clarity in amplification, vernacular instrumentation, and players who play like rock musicians – i.e. with a soloistic attitude and stage presence – that I would consider a vital and indispensable factor in the development and successful delivery of the totalist style. I would probably not have written any of my totalist pieces if I didn’t have access to the instrumental doublings of the E.A.R. Unit. They just wouldn’t sound right.

It’s true, there was generally a kind of mixed, all-or-partly amplified ensemble sound that made those pieces come off. Just as Nancarrow had to harden his piano hammers to keep his counterpoint masses from softening into mush, totalist music needed amplification and instruments with percussive attacks to bring off the gear-shifting tempo contrasts.

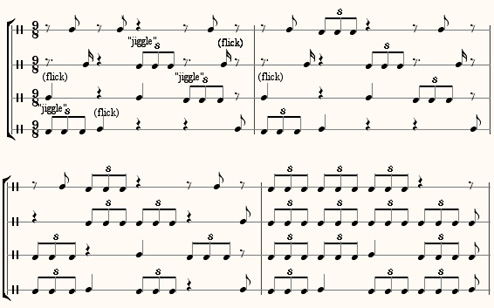

Although I might also mention that one of Art’s most rhythmically inventive works, The Paces of Yu (1990), was scored for solo berimbau (a simple Brazilian stringed instrument) accompanied by pencil sharpeners, window shutters, plucked wooden rulers, wooden boxes, mousetraps, and fishing reels. Here’s a small excerpt from the score, showing a section for flicked and jiggled window shutters. It employs a fairly common totalist or metametric rhythm, triplets in odd-numbered meters, so that downbeats contradict the momentum set up by the triplets, and also a gradual rhythmic process, showing the inheritance from minimalism:

And here’s a recording, courtesy of the California Ear Unit and O.O. Discs. (Warning, the opening is very soft for a few minutes.) It’s hardly a sonically typical totalist example, but a suitably whacky bit of pure Jarvinen.