main: March 2009 Archives

I just saw Into the Wild for the second time, and it was even better than the first.

I just saw Into the Wild for the second time, and it was even better than the first.Here is a recap of what I wrote before, with some added reflections.

The film was directed by Sean Penn, whose personality and opinions I have little use for, but whose artistry I find unsurpassed. It is based on the eponymous best-seller by Jon Krakauer, about Christopher McCandless, a young man who "dropped out," as they used to say in the sixties, only without "tuning in" to any movement or "turning on" with any known drug.

McCandless is played beautifully by Emile Hirsch, and the soundtrack by Michael Brook and Eddie Vedder achieves perfection. (I don't use that word very often.)

What McCandless did was abandon family, friends, future prospects, and affluent lifestyle, to embark on a quest without definition that, to judge by the film (I have not read the book), acquired definition as it went along. After two years of living as a voluntary hobo (he renamed himself "Alexander Supertramp"), a hippie (he bonded with a counter-cultural tribe living in RVs), and a latter-day alms-seeker, he trekked alone into the Alaskan wilderness, where after 112 days of foraging for food and living in an abandoned bus, he died of starvation.

Into the Wild is not only a visual masterpiece (all the more stunning for not having been generated by a computer) but also a masterpiece of philosophical story-telling. McCandless kept a diary, which along with the testimony of his sister, provide the outline of his character and story line. But most remarkably in this age of non-literary, even anti-literary film making, the film's other source is the books McCandless carried with him, not just in his knapsack but in his head. This film lacks all the prissy self-consciousness with which many American films portray literate characters.

Of all the authors mentioned and quoted, the one I wondered about most was Tolstoy. The film's great subject is the American ideal of individual freedom, its promise and pitfalls, played out on a richly rendered American canvas. (Among other things, it is a fine travelogue.) How does Tolstoy figure into that?

Stay with the film, all the way to the end, and you will see. Into the Wild possesses Tolstoy's most essential quality: an ability to move from the center of everyday existence to the outer periphery, where life and death and transcendence meet and touch; and to do it all with a sure hand that, in its power and wisdom, resembles the hand of God. This is the Tolstoy of the Confession, who journeys through doubt, cynicism, flight, and heartache; only to realize his yearning for human connection too late, at which point he must face his terror of death, which ends in a moment of transcendence that may or may not last beyond this life.

There are many questions about McCandless, who seems to have partly desired his own end. For example, he ventured into the wild with no map, so he did not know that the spring-swollen river that blocked his return could have been crossed by a hand-operated tram a quarter of a mile away.

To say this is to miss the point, however. As Krakauer has noted, McCandless was on a spiritual quest to find "a blank spot on the map," and because there are so few of these left, "he made the world a blank spot for himself, by throwing away the map."

March 15, 2009 9:52 AM

| Permalink

Finally, someone finds the courage to say out loud that comic book movies are stupid, stale, and boring. I have not seen Watchman, and I have no intention of seeing Watchman. But thanks to A. O. Scott's review this Sunday, I know I am not alone in my aversion.

I understand that this trend is based on a purely commercial calculation: movie theaters make money not from tickets but from popcorn and candy, so there is a lot of pressure to make films for the popcorn-and-candy crowd. The problem is, these films go out to the rest of the world, and give the impression that Americans all have the mindset of an adolescent boy with limited education and imagination, trying to make sense of the world as it was 25 years ago.

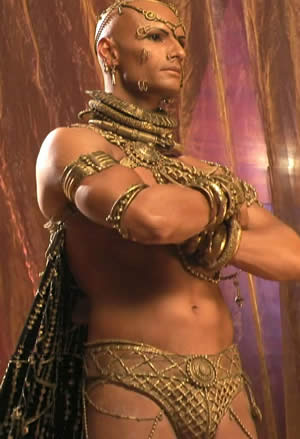

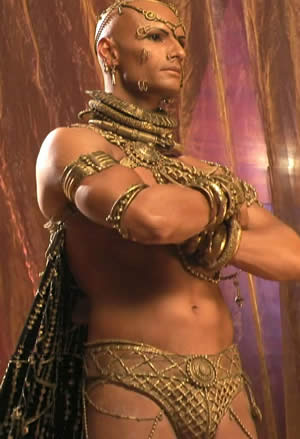

Zack Snyder's last film, the execrable 300, which represented the ancient Persians as a mob of subhuman degenerates, did what no one in the Bush administration was ever able to do: it united the Iranian people with their government in denouncing American culture.

Zack Snyder's last film, the execrable 300, which represented the ancient Persians as a mob of subhuman degenerates, did what no one in the Bush administration was ever able to do: it united the Iranian people with their government in denouncing American culture.

I understand that this trend is based on a purely commercial calculation: movie theaters make money not from tickets but from popcorn and candy, so there is a lot of pressure to make films for the popcorn-and-candy crowd. The problem is, these films go out to the rest of the world, and give the impression that Americans all have the mindset of an adolescent boy with limited education and imagination, trying to make sense of the world as it was 25 years ago.

Zack Snyder's last film, the execrable 300, which represented the ancient Persians as a mob of subhuman degenerates, did what no one in the Bush administration was ever able to do: it united the Iranian people with their government in denouncing American culture.

Zack Snyder's last film, the execrable 300, which represented the ancient Persians as a mob of subhuman degenerates, did what no one in the Bush administration was ever able to do: it united the Iranian people with their government in denouncing American culture.

March 9, 2009 9:05 AM

| Permalink

Don't read the reviews of Arranged (2007), a stunning little film about the friendship between two teachers in a Brooklyn public school. They systematically miss the point, which is that despite their differences, Rochel (Zoe Lister-Jones) and Nacira (Francis Benhamou) have more in common with each other than they do with the larger society. This point is hard to accept, it seems, because Rochel is an Orthodox Jew and Nacira is a Syrian Muslim.

Don't read the reviews of Arranged (2007), a stunning little film about the friendship between two teachers in a Brooklyn public school. They systematically miss the point, which is that despite their differences, Rochel (Zoe Lister-Jones) and Nacira (Francis Benhamou) have more in common with each other than they do with the larger society. This point is hard to accept, it seems, because Rochel is an Orthodox Jew and Nacira is a Syrian Muslim.So what do they have in common? Here the film swims directly against the current of most independent films by inviting us to sympathize with two attractive young women who are firmly committed to female modesty, chastity, respect and obedience toward parents, and arranged marriage. Instead of being trapped by these customs, both characters find them a refuge against the wider culture.

For example, when the school principal, a liberated woman of a certain age (Marcia Jean Kurtz) asks the new teachers to introduce themselves to the rest of the staff by sharing a "really juicy secret," Rochel and Nacira cringe together. And I for one cringe with them.

Still, what makes the film work is not its endorsement of what most Americans regard as utterly retrograde social customs. What makes it work is its light, deft, comic touch that spares no one, least of all the matchmaking adults who drag Rochel and Nacira to meeting after meeting with men they would rather die than marry. It matters a lot that this is arranged marriage, not forced marriage. The young women get to choose, and although the choices look pretty grim for a while, everything works out in the end (with some creative tweaking that is itself a tribute to individualism and freedom).

March 1, 2009 7:11 PM

| Permalink