This is Not Nostalgia

Invited by the Wall Street Journal to do a short piece on Woodstock, this is what I came up with:

Invited by the Wall Street Journal to do a short piece on Woodstock, this is what I came up with:"Both a Dream and a Nightmare"

The 1969 Woodstock festival wasn't held in Woodstock, N.Y., but in a dairy-farming hamlet 43 miles away with the evocative name of Bethel. On the 40th anniversary of what has clearly become a milestone in American cultural history, there is a surprising resonance between the meanings we take from Woodstock and Bethel as mentioned in the Bible.

Bethel first appears in Genesis as the place in Canaan where Jacob dreams of a stairway to heaven with "messengers of God . . . going up and coming down it." This resonates with the notion of Woodstock as a vision of ideal community, where all may enjoy total freedom because all are committed to peace, love and harmony.

The second mention is in 1 Kings, where Bethel is one of two sites where the ruler Jeroboam corrupts his people by erecting a shrine to the Golden Calf. To less starry-eyed observers of Woodstock, this reference evokes a nightmare vision of human beings given over to self-indulgence, debauchery and destruction.

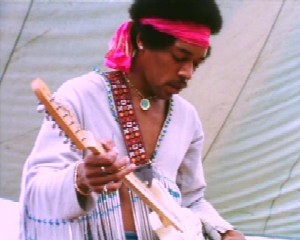

Which is the true picture? Most Americans embrace one and reject the other, a reflection of how polarized we have been ever since that summer when Jimi Hendrix kissed the sky and Neil Armstrong walked on the moon. Yet one reason for the continuing allure (not to mention commercialization) of Woodstock is that it was neither all dream nor all nightmare. It was both.

On the dream side, the first performer of the weekend, folk singer Richie Havens, recalls looking out at the sea of humanity and feeling "at the exact center of true freedom." Asked to keep playing until the next act could arrive, Mr. Havens heroically obliged, ending a three-hour set with an improvised medley of the old spiritual "Motherless Child" and a rousing chorus consisting of one word: "Freedom!"

Watching this inspired performance, it's hard not to think of certain subsequent mass meetings--in Krakow, East Berlin, Beijing, Kiev, Tehran--that expressed the same primal urge to break free of all restraint. Some cultures fear and distrust this urge, but American culture applauds it--even though our political tradition teaches that true freedom is not the total lack of restraint but the capacity to substitute self-restraint for the chains of arbitrary power.

Surprisingly, this lesson was in evidence at Woodstock. The event was banned from two other upstate communities because of dire predictions of "maddened youths" rampaging through the streets. Given the violent demonstrations, assassinations and bizarre crimes occurring at the time, these predictions were not paranoid. Yet Woodstock proved them wrong, largely through the efforts of the Hog Farm, an exceptionally well-organized hippie commune whose members, in the words of local merchant Art Vassner, "kept the peace. They were dirty, but they were nice."

Yet chaos was never far from the surface. Abbie Hoffman, leader of the anarchist Youth International Party (Yippies), grabbed the microphone during a performance by the Who to make a political speech. And it quickly became obvious that any attempt to restrict admission would result in a riot, so the sale of tickets was abandoned, along with the fence surrounding the concert area.

Among the various parties taking credit for cutting that fence was another anarchist group called Up Against the Wall Motherf**kers. Significantly, UAW/MF emerged not from any organized political movement but from the arty fringes of Manhattan's Lower East Side, where the priority was not to end racism or war but to ridicule and attack "bourgeois" figures such as Andy Warhol and rock impresario Bill Graham.

A few years later, such adolescent nihilism would produce its own species of music: punk rock. But at Woodstock, this had not yet happened. Indeed, one of the main forces keeping the peace was the relatively upbeat tone of the music. From folk acts like Joan Baez to rock groups such as Creedence Clearwater Revival, the performers drew on a rich and varied array of vernacular American sounds, ending with Jimi Hendrix's fractured "Star-Spangled Banner," a brilliant virtuoso piece that says more about the temper of the times than a hundred political tirades.

Still, the unhappy fate of Hendrix, who died the following year, brings us back to the Golden Calf. In the late 1960s drugs were held up as a quick and easy path to spiritual transcendence. At Woodstock, the worship of this particular false idol peaked during the performance of Sly and the Family Stone. Watching Sly Stone power his way through "I Want to Take You Higher," it is obvious that his roots lay in the Pentecostal Church. But on this occasion he was not referring to the Holy Spirit.

It is a curious irony that most of the nostalgic films about the Woodstock era, from "Forrest Gump" to "Across the Universe," are love stories, because true love was hardly the watchword of the time. On the contrary, the motto was "If it feels good, do it." Of the trio "sex, drugs and rock 'n' roll," the first item remains the most divisive. This is because while the orgy at Woodstock may not have reached biblical proportions, it did encourage the 1960s generation to regard sexual fidelity as an antiquated Puritan notion, and erotic liberation as the key to sanity and happiness. It would take another generation for that to show up as a really bad trip.

Copyright 2009 Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved

August 15, 2009 5:55 PM

| Permalink