April 2009 Archives

To prepare for the trip, I read several articles about Oman, but the best thing I read was Arabian Sands, by the extraordinary British explorer Wilfred Thesiger. Published in 1959, the book relates his travels with the Bedouin tribes across the great desert of southern Arabia, which the Arabs call simply "the Sands."

Thesiger's descriptions of that amazing landscape are among the best ever written in English. But what really impressed me was his account of the Bedouin. Yes, he had a bad case of what the US State Department calls "localitis." He went native with a vengeance. But read him, and you will see it was a beautiful vengeance. So greatly did he admire the Bedouins' physical stamina and nobility of character, he bemoans the coming of that bundle of blessings and curses we call modernity.

In particular, he deplores the advent of paved roads, asserting at one point that "the very slowness of our march diminished its monotony. I thought how terribly boring it would be to rush about this country in a car."

What better segue to Yellow Asphalt (2000), a brilliant, searing film by the Israeli film maker Danny Vereté. Seven years in the making, the film tells three tales, each longer than the one before, about the encounter of the Bedouin with late 20th-century modernity. The sands here are those of the Judean desert, and the cast of the film includes both Israelis and members of the Jahalin Bedouin tribe. And in keeping with Thesiger's spirit, it opens with an image of a huge tractor-trailer careening along an empty highway, only to round a curve and accidentally run over a Bedouin boy.

I won't tell you the plots, because while the first and second end on a darkly comic note, the third unfolds with all the stark inevitability of a Greek tragedy. And like a Greek tragedy, it contrasts the clumsy blows of fate with the delicate resilience of the most noble human characters. So keep an eye on Abed, the young Bedouin in the third tale. He would not be out of place in Thesiger's memoir.

April 19, 2009 7:18 PM

| Permalink

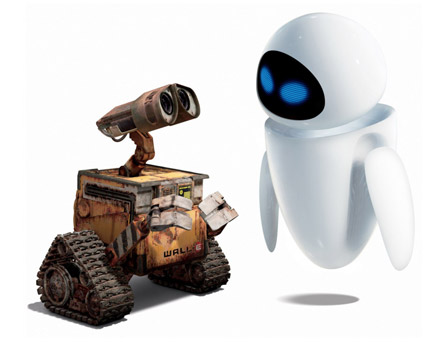

How can you tell that Wall-E is a departure from the many cliches of Disney animation? By looking at the eyes of the main character, Wall-E, a rusty little trash compactor trundling through the wreck of a city choked to death on its own garbage.

How can you tell that Wall-E is a departure from the many cliches of Disney animation? By looking at the eyes of the main character, Wall-E, a rusty little trash compactor trundling through the wreck of a city choked to death on its own garbage.Instead of the big, expressive, black-and-white peepers seen on every cartoon character from Mickey Mouse to Remy the Chef (in Ratatouille), the eyes of Wall-E are set like lenses into his binoculars-shaped head, and like binoculars, their only form of expression is to adjust focus.

Add the fact that the initial half hour of Wall-E contains almost no dialogue, and the challenge becomes clear: How to create empathy for a machine whose day job -- building skyscrapers of rubbish in a city already full of them -- makes Sisyphus' rock-rolling look fulfilling?

Well, first we see that trash compacting is just a day job. Wall-E's passion is collecting objects of seeming value and finding a use for them. In other words, he's both an archeologist and a recycler. Second, we see his concern for his only companion, a cockroach who also (mercifully) does not have big expressive eyes but actually looks and moves like a six-legged insect.

The plot gets underway when Wall-E collects a very curious item: a tiny green seedling that, apart from the cockroach, is the only sign of biological life for miles around. Shortly after this, a noisy space ship lands and ejects an elegant little ovoid probe by the name of Eve.

Wall-E is smitten, and gives Eve the seedling, thereby setting off all her bells and whistles, since she is expressly designed to probe for signs of life on Earth. She is recalled to her mother ship, one of several gigantic orbiting residence for what is left of the human race, and Wall-E follows her.

Some have objected to this part of the film, because what Wall-E finds on that orbiting city is a parody of America: a huge garish mall, run by a monopolistic corporation (B&L, for Buy & Large), and inhabited by obese consumers so enervated by their own technological utopia, all they can do is drift around on floating lounge chairs, sipping Big Gulps and amusing themselves with futuristic iPhones, while being waited on by a legion of specialized gadgets.

But these critics protest too much, because once these passive creatures are liberated from the oppressive rule of the super-computer in charge of the ship (who strongly resembles Hal in 2001: A Space Odyssey), they prove brave, good-hearted, and more than willing to reclaim their ruined planet. All's well that ends well.

But these critics protest too much, because once these passive creatures are liberated from the oppressive rule of the super-computer in charge of the ship (who strongly resembles Hal in 2001: A Space Odyssey), they prove brave, good-hearted, and more than willing to reclaim their ruined planet. All's well that ends well.And for me, the eyes have it. The delights of Wall-E lie not in the cliched nature of its satire but in the non-cliched nature of its imagery. To this lover of animation who dreams of hiring Pixar's best to make full-blown versions of Homer and Dante, any step in that direction is welcome.

April 7, 2009 9:03 AM

| Permalink