If it’s coming your way, you won’t do wrong to grab tickets to Tango Buenos Aires’ current touring show, “Song of Eva Perón.” Already immortalized in music and on film, Evita’s physical portrait here — mostly an energetic one, as considered here through the lens of Argentine tango — adds subtle dimension to her mystique.

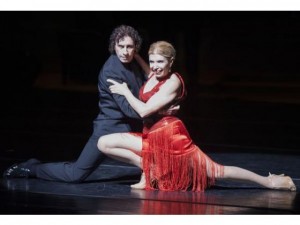

Nestor Gude and Lucia Alonso in Tango Buenos Aires’ “Song of Eva Peron.” Photo: Kevin Sullivan, Orange County Register

Eva Perón’s legendary posture grew from her torso – arms thrown open sympathetically or raised high in forceful gesticulation, always projecting far over the massed crowd. Though it feels as if she should have had similarly sculpted, demonstrative legs, according to biographers, Perón thought her ankles were fat and preferred to downplay them.

With its new touring show, “Song of Eva Perón,” the terrific Tango Buenos Aires company redraws Perón’s physicalization to include cunning legs, smoldering rhythms and the peculiar masculine-feminine tensions of tango. And it is indeed faithful to the era: During Perón’s time, the snaky, stylized Argentinian dance saw a strong resurgence.

A semi-narrative work choreographed by Hector Falcon, “Song of Eva Perón” at first seems way off-track. The two-act production opens with a scarily generic Broadway-esque number featuring a late-era Evita (Lucia Alonso) standing centerstage, shrouded in white, singing Fernando Marzan’s tuneful dirge, “The Wish to Give It All,” while company members crawl in from the wings on their hands and knees, looking awkward and contrived in restrictive suit pants and pencil skirts.

When the song ends, the scene quickly segues back to the train station where the Argentinian heroine is now a young ingenue, heading off to Buenos Aires to change her luck. Depicted in smart dress, traveling solo with a neat little suitcase, she’s such a whitewashed, starstruck hopeful that it is only when she nods off, and a dream image of Evita’s iconic stumping political figure comes forward, that it’s at all conceivable that we’re anywhere near South America.

Luckily, the narrative is sheared off completely after this, ridding the piece of its tangled, unskilled “biographical” scenarios in exchange for illuminating, poetic portraits of both the era and the combined power of Evita and Juan Perón (Paula Arias and Hector Falcon). Adorned with the 1940s costume and hair designs, and live renditions of Astor Piazzolla’s priceless tangos played by a feisty six-piece band, the ensuing two dozen or so dances feature strong variety and composition, each one revealing new turns on the strangely aloof tango essence, danced buoyant by the company’s fascinating multiage cast.

Standout duets include one number in which a couple hold their faces close for almost the entire dance, their cheeks softly sealed while their feet and legs and hips write all manner of calligraphic flourishes. And a knotty group dance, in which five dancing couples weave and swap partners, moves at inhuman speed, with nary a single transitional step. Women spin away from one partner, snap into place with another, whip out a few dips and flicks, and move on again.

Tango always demonstrates a range of masculine and feminine qualities within its form. “Song of Eva Perón” took that dichotomy one step further by presenting mesmerizing, layered sections for the male dancers that felt to indicate both a society that Evita breached and an energy she grew to possess. During one section of fluttering male footwork, she stands watching at the sidelines, stilled, as if both admiring Juan and absorbing the men’s speed and assurance.

Yet the work also portrays a distinctive, impervious machismo. Act I climaxes with a transporting, expanded scene featuring men – in unison and solos – spinning and whipping boleadoras, those ropes with balls at the ends that were used by cowboys to knock cattle down for branding. Nestor Gude’s phenomenal solo is conducted at speeds so fast that the drawn arcs consolidate in the air, their spinning source only indicated when the ropes graze the ends of his hair.

Abstract, yet essential, these cosmic orbits feel to get at the supernaturality of Evita in her lifetime and beyond. In Act II, when Arias is tangoing with Falcon, her own superior formal precision, musicality and muscular organization – as she executes huge dips and perfectly coiled spins – recalls the suspension and dazzle of those earlier orbs and helixes.

Situating the program on the informal Renée and Henry Segerstrom Concert Hall stage in Costa Mesa, as compared with the full-scale Segerstrom Hall, had its gifts and challenges. Aside from some mic problems when dancer Juan Corvalan was drumming, the music quality was excellent, and the tight, acoustical space supported the work’s demonstration of how each individual instrument – piano, bandonions and strings – might spur different qualities of dance.

There were some spacing kinks during the larger numbers, and the single wing on each side made for some creative entrances and exits. Yet despite the absence of a back scrim in the hall, the overhead lighting design was remarkably keen and atmospheric, ultimately making the compressed scene feel like a win, energetically and scenically.

Sustained by the slow burn and fiery explosions of the male unison work, as well as the languor born from Arias’ confident musicality and physical control, “Song of Eva Perón” delivers an enlarged, lyrical physicality to a woman poised eternally on the Casa Rosada balcony.

[A version of this piece ran in the Orange County Register.]