main: July 2009 Archives

The evidence is overwhelming that someone has gathered up the world's editors and placed them on a ship to sail around the globe, over and over, all by themselves, never to dock again.

The evidence is overwhelming that someone has gathered up the world's editors and placed them on a ship to sail around the globe, over and over, all by themselves, never to dock again.

How would you like to be author of that boat's daily newsletter, or its menus? ("No, I beg to differ, our style requires two Ls in "fillet"!)

Just as bad editing drains the life from a living thing as does as any fanged character on Alan Ball's True Blood, good editing does the opposite. Sometimes that means as little as a kind word to a nervous scribe, or a swashbuckling challenge, or a left-field query, surely between equals.

One editor, of course, is always enough.

Readers may recognize the Man Ray photo above of Margaret Anderson, not the character played by Jane Wyatt on TV's Father Knows Best, but the founder and editor of The Little Review, who with lover and coeditor Jane Heap first published, in serial form, James Joyce's Ulysses. I think it my duty as a typical example of that hybrid monster of journalism, editor-writer, to quote from My Thirty Years' War, Anderson's memoir of time spent with the likes of Stein, Hemingway, H.D., and D.H. Lawrence under lapis lazuli modernist skies.

Does this editor protest too much, or not enough?

I was having a marveolus time being an editor. I was born to be an editor. I always edit everything. I edit my room at least once a week. Hotels are made for me. I can change a hotel room so thoroughly that even its proprietor doesn't recognize it. I select or reject every house seen from train windows and install myself in all the chosen ones, changing their defects, of course. Life becomes confusing. ... Where haven't I lived?

I edit people's clothes, dressing them infallibly in the right lines. I am capable of becoming so obsessed by the lines of a well-cut coat that its owner thinks I am flirting with him before I've realized he is in the coat. I change everyone's coiffure -- except those that please me -- and these I gaze at with such satisfaction that I become suspect. I edit people's tones of voice, their laughter, their words, I change their gestures, their photographs. I change the books I read, the music I hear. In a passing glance I know a man's sartorial perfections or crimes -- collar, cravat, handkerchief, socks, cut of shoulders, lapels, trousers, placement of waistline, buttons, pockets, quality of material, shoes, walk, manner of carrying stick, angle of hat, contour of hair. It is this incessant, unavoidable observation, this need to distinguish and impose, that has made me an editor. I can't make things. I can only revise what has been made. And it is this eternal revising that has given me my nervous face.

Me, I would delete that last sentence at least, maybe the last three.

(At right, "The Little Review" coeditor Jane Heap. Cut of shoulders seems fine.)

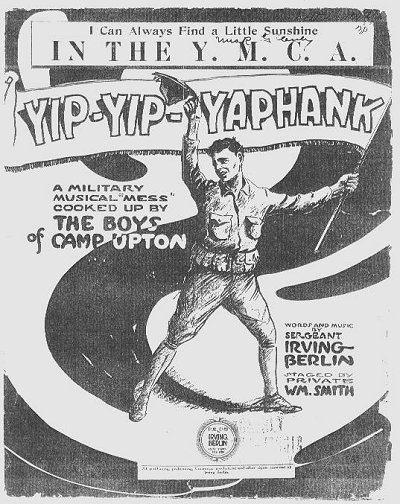

Most everyone old enough to know who Irving Berlin is knows that "Oh! How I Hate to Get Up in the Morning" was written in 1917 at Camp Upton in Yaphank, Long Island when the composer was called "Sarge." It became part of a musical revue called Yip! Yip! Yaphank! I know it's not Yip, Yip, Yaphank or Yip, Yap Yaphank, both common mistakes, because the New York Times review of its 1918 run at Manhattan's Century Theatre (on the Upper West Side!) spells it with the three exclamations -- way before the decimation of all our copy desks, so it must be right.

Most everyone old enough to know who Irving Berlin is knows that "Oh! How I Hate to Get Up in the Morning" was written in 1917 at Camp Upton in Yaphank, Long Island when the composer was called "Sarge." It became part of a musical revue called Yip! Yip! Yaphank! I know it's not Yip, Yip, Yaphank or Yip, Yap Yaphank, both common mistakes, because the New York Times review of its 1918 run at Manhattan's Century Theatre (on the Upper West Side!) spells it with the three exclamations -- way before the decimation of all our copy desks, so it must be right.

Oh, wait. The songsheet above has it otherwise."We can't run the piece until we're sure of the spelling," the ever-vigilant copy desk says.

By the way, google-eyed (small G) Eddie Cantor put the number over.

Yaphank, a long-settled town of sprawling charm, is the site this weekend (July 10-12) of a hybrid event by my warm, inventive friend Tricia Foley, author of the just-out At Home With Wedgwood: The Art of the Table. She wanted to gather friends, neighbors, and random visitors to her 1820 home and its various satellite sheds on Lily Lake. She also wanted to collect and display dishes, linens, plants, and produce that "objectify" and condense the sort of savvy, local idealism that was once called American utopian, and sell them. She wanted a general store; she wanted a popup store. She hoped that style and fellowship could spend an afternoon together.

Yaphank, a long-settled town of sprawling charm, is the site this weekend (July 10-12) of a hybrid event by my warm, inventive friend Tricia Foley, author of the just-out At Home With Wedgwood: The Art of the Table. She wanted to gather friends, neighbors, and random visitors to her 1820 home and its various satellite sheds on Lily Lake. She also wanted to collect and display dishes, linens, plants, and produce that "objectify" and condense the sort of savvy, local idealism that was once called American utopian, and sell them. She wanted a general store; she wanted a popup store. She hoped that style and fellowship could spend an afternoon together.

So Trish put together what she calls the New General Store that I would call popup utopia.

Chef Roy Hardin makes a fine locavore pizza, too.

For an automatic alert when there is a new Out There post, email

Lettuce Soup. For vegephiles. To my friends Meredith, Sasha, and Daphne.

Lettuce Soup. For vegephiles. To my friends Meredith, Sasha, and Daphne.If you can score a real head with dirt still on it, or harvest your own -- I know, lets out most of my faithful correspondents -- or just pretend with what's left in the fridge, this recipe will make your lettuce almost sumptuous. And, unless you're an Asian cook, chances are this will the first time you've put heat to this particular leaf.

Ingredients: that lettuce, and it can be a few days gone, because it will still throw its faded lettuceness into the broth; garlic scapes or garlic; any hard grating cheese, Pecorino is fine; pine nuts or leftover almonds from your weekend party; olive oil, the Greeker and stronger the better; vegetable or chicken broth, boxed organic or that high-rent frozen kind, or make your own. Or canned. Or just use water. Cheap is a plus.

Basically, you're wilting the lettuce in a dead-simple broth whose flavor has been "bloomed" by a few spoons of basilless pesto. (Basil trumps lettuce.) You can make the pseudopesto in advance; the oil will leach flavor from the scapes and share itself with the nuts.

Get out your processor, blender, mortar and pestle (yes, I know), or knife, and make a pounded, chopped mash of the nuts, cheese, and scapes or garlic. Whip in the oil. Ingredient ratios can vary, but mix it up so the result is one color, maybe two, not three or four. Taste. If you use scapes and almonds as opposed to garlic and pignoli, the texture may be sandy, but don't fret. Maybe add some salt if the cheese doesn't do that trick already.

Heat a cup of broth per person.

By the way, this is an ideal solipsistic solo lunch. The food will provide the company you need.

Add one tablespoon per person of that partial pesto to the broth, or even a bit more, and watch the oil float out of it like a ghost and the tiny particles of flavoring disseminate. What a pleasing aroma, the magazine would say.

Rip or cut the lettuce into wide strips or pieces at least half the size of the leaf. When the broth is steaming, throw it all in, stir for a minute or two at most, pour into your flattest, widest brimmed bowl, plucking out the just-collapsed greens that remain in the pot, wipe edge (please, neatness counts), and serve immediately with hard-crust bread or at least toast.

Elizabeth David, an English food historian of convincing chic and poet whose poems were recipes, first alerted me to lettuce soup in her earthy and elegant 1960 correction to English food, French Provincial Cooking. She assumed that her readers also read French, which is odd, but she was concerned that her research be understood in an authentic mode. The lettuce recipe, then, was named "Potage du Père Tranquille," after some obscure Capuchin monk who was particularly susceptible to the well-known quieting effects of lettuce. She recommends the dish as "useful for those who have more lettuces in their gardens than they can eat as salads."

Elizabeth David, an English food historian of convincing chic and poet whose poems were recipes, first alerted me to lettuce soup in her earthy and elegant 1960 correction to English food, French Provincial Cooking. She assumed that her readers also read French, which is odd, but she was concerned that her research be understood in an authentic mode. The lettuce recipe, then, was named "Potage du Père Tranquille," after some obscure Capuchin monk who was particularly susceptible to the well-known quieting effects of lettuce. She recommends the dish as "useful for those who have more lettuces in their gardens than they can eat as salads."That's the advice I remembered. What a curious thing to say, I had thought when I first read it so many years back. Imagine, kitchen gardens in sooty London, Manhattan. And "lettuces," a plural form that meant I would never feel comfortable at the author's table. Her iceberg, I had joked, could only be the one that sank the Titanic.

Yet as I turned through her fruity-voiced, pleasure-filled instructions and learned the many ways to cook an egg and how to discern exactly when the optimal point was reached for a baked yolk or fillet of this or that, I fell in love. Or maybe I should say that in some small but permanent manner, I was overtaken by the writer's senses.

Do you lose your sense, your sense of yourself, when someone's sensibility inhabits your own? No, not at all. Instead, that gentle transfer is the way cooking breeds a certain human sympathy, a "sense" of being at least two people at once.

Elizabeth David's Potage du Père Tranquille, or Lettuce Soup

Two large whole lettuces, or the outside leaves of 3, about 1 pint of mild chicken or veal broth and 1 pint of milk, seasonings, a little butter or cream.

Cut the carefully washed lettuce leaves into fine ribbons; put them in a saucepan with just enough broth to cover them. Let them simmer gently, adding a little more liquid, until they are quite soft. Sieve them, or puree then in the electric blender. Return the purée to the pan, gradually add the rest of the broth and enough milk to make a thin cream. Season with salt if necessary, a lump or two of sugar, and a scrap of nutmeg. Before serving stir in a small lump of butter or a little thick fresh cream. Makes five or six helpings.

For an automatic alert when there is a new Out There post, email

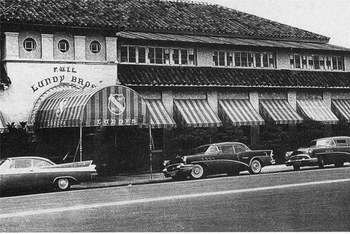

One of the reasons I became what people call a "food writer" was my clam-broth baptism in the behemoth, much-mourned Brooklyn restaurant called Lundy's. That fish palace on Sheepshead Bay coalesced a constellation of 20th-century American values: collective melting-pot festivity (it seated more than 3000), the promise of local unpolluted cornucopia (littlenecks and fluke from right outside, sort of), institutionalized racism (underpaid all-black staff), and working-class strife (a bloody strike).

My personal attachment, however, was identical to that of many Brooklyn-Jewish contemporaries: beaten biscuits hot enough to melt the icy butter-pat, sandy clams, salty bisque -- and a first view of fat, glistening lobster and its pillowy reward inside.

My father, who beamed to see his two boys join him in the pleasures of the table, had one signature selfishness (that I knew of, anyway): Lundy's lobster was his, only his. Mom didn't really enjoy it the way he did, and it was out of bounds -- as was most everything a la carte -- for Leslie and me.

Yes, Leslie. He hated his name, always said that I was the one who should have been Leslie. Sweet.

One of the reasons I became what people call a "food writer" was my clam-broth baptism in the behemoth, much-mourned Brooklyn restaurant called Lundy's. That fish palace on Sheepshead Bay coalesced a constellation of 20th-century American values: collective melting-pot festivity (it seated more than 3000), the promise of local unpolluted cornucopia (littlenecks and fluke from right outside, sort of), institutionalized racism (underpaid all-black staff), and working-class strife (a bloody strike).

My personal attachment, however, was identical to that of many Brooklyn-Jewish contemporaries: beaten biscuits hot enough to melt the icy butter-pat, sandy clams, salty bisque -- and a first view of fat, glistening lobster and its pillowy reward inside.

My father, who beamed to see his two boys join him in the pleasures of the table, had one signature selfishness (that I knew of, anyway): Lundy's lobster was his, only his. Mom didn't really enjoy it the way he did, and it was out of bounds -- as was most everything a la carte -- for Leslie and me.

Yes, Leslie. He hated his name, always said that I was the one who should have been Leslie. Sweet.

We lived in a postwar apartment on Ocean Avenue, close enough to walk as a family on weekends to an early Lundy's meal. When we were led through the cavernous dining rooms, the immense din, the metallic kitchen clatter, the aural and visual evidence of irrevocable mass pleasure made me as happy as I think I have ever been.

Still, for me, growing up meant ordering anything I wanted -- and paying for it myself. Of course, I never did the latter when I was a restaurant critic.

Anyway, once we brought Grandma. Mary Weinstein -- Mary? Is that a Jewish name? -- kept a kosher home, but my father, the black-sheep favorite of seven, had a trick. He began months before telling her that there was a special Weinstein dietary "dispensation" for lobster. He worked it, and worked it. Just for Weinsteins, he said, grinning his used-car salesman grin. Just for us.

"Here, Mom," and he lifted a chunk of his trayfe fra diavolo on his fork to her mouth.

Can you imagine the expression of warring impulses on her face? I watched my white-haired grandma sink in luxurious defeat. Her darling Hashel could do that every time.

If they had had websites named "Renegade Kosher" then, "Weinstein" would have been a constant keyword.

So what drew out this piece of delicate nostalgia? I was recently asked to eat and rate the kosher offerings at the insultingly expensive Citi Field and Yankee Stadium by the folks at the Forward. Results? I hope you're a Mets fan, or at least can pretend for just those few hours that I'm your dad and allow yourself an online, adoptive, baseball-park "Weinstein dispensation."

Happy 4th of July,

We lived in a postwar apartment on Ocean Avenue, close enough to walk as a family on weekends to an early Lundy's meal. When we were led through the cavernous dining rooms, the immense din, the metallic kitchen clatter, the aural and visual evidence of irrevocable mass pleasure made me as happy as I think I have ever been.

Still, for me, growing up meant ordering anything I wanted -- and paying for it myself. Of course, I never did the latter when I was a restaurant critic.

Anyway, once we brought Grandma. Mary Weinstein -- Mary? Is that a Jewish name? -- kept a kosher home, but my father, the black-sheep favorite of seven, had a trick. He began months before telling her that there was a special Weinstein dietary "dispensation" for lobster. He worked it, and worked it. Just for Weinsteins, he said, grinning his used-car salesman grin. Just for us.

"Here, Mom," and he lifted a chunk of his trayfe fra diavolo on his fork to her mouth.

Can you imagine the expression of warring impulses on her face? I watched my white-haired grandma sink in luxurious defeat. Her darling Hashel could do that every time.

If they had had websites named "Renegade Kosher" then, "Weinstein" would have been a constant keyword.

So what drew out this piece of delicate nostalgia? I was recently asked to eat and rate the kosher offerings at the insultingly expensive Citi Field and Yankee Stadium by the folks at the Forward. Results? I hope you're a Mets fan, or at least can pretend for just those few hours that I'm your dad and allow yourself an online, adoptive, baseball-park "Weinstein dispensation."

Happy 4th of July,

For an automatic alert when there is a new Out There post, email

For an automatic alert when there is a new Out There post, email