Recently in main Category

"I learned about cooking and flavor as a child."

"I learned about cooking and flavor as a child." Growing up, we would sow onion seed in the garden and then thin a lot of them out before their bulbs got too big. We chopped them up, sautéed them in bacon fat, poured in heavy cream, and ate them for breakfast. This recipe is not quite as rich as that, but uses scallions in a way that tastes just delicious. In my opinion, they are an underused vegetable and taste almost as good today as they did years ago.Breakfast. Scallions, bacon grease and cream for breakfast. Even though her Freetown, Virginia family, settled there by her slave grandparents, was a larger collection of relatives than my nuclear Brooklyn four, what the hell. If Miss Lewis could look back without reservation, so may I.

Do you want to pay for your news with dead trees or the predation of oil? In this case, the form of payment itself makes news.

Do you want to pay for your news with dead trees or the predation of oil? In this case, the form of payment itself makes news.  Normally, my single question to you at the end of this post would be posed via Twitter or Facebook. But so many smart classical-music mavens are my Artsjournal neighbors that I thought I might borrow some of your tidewrack readers for just one time.

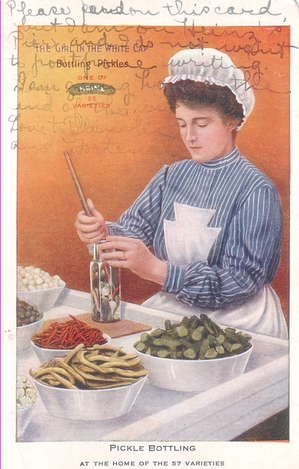

Normally, my single question to you at the end of this post would be posed via Twitter or Facebook. But so many smart classical-music mavens are my Artsjournal neighbors that I thought I might borrow some of your tidewrack readers for just one time. I was taken aback by my failure to find a worthy pickle cocktail.

I was taken aback by my failure to find a worthy pickle cocktail.No Worcestershire; no extra salt, and be careful with the amount of your choice of pepper till you taste at the end; lime and lemon juice, or lime only. Two jiggers of gin, a half jigger of brine. During summer, use diced fresh tomatoes, skin and all, mash together, then ice and stir. The rest of the time, use the usual juice.

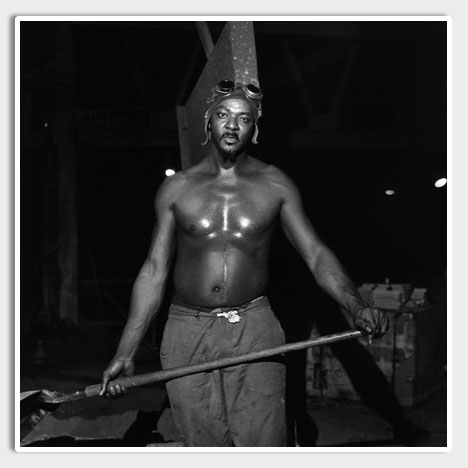

The impact of the fire had to do with why the girls, women and men died. Every single death was preventable. Greed and a corresponding lack of humanity were responsible. The two men who owned the fatal factory got off because one lawyer confidently defended a world of corruption.

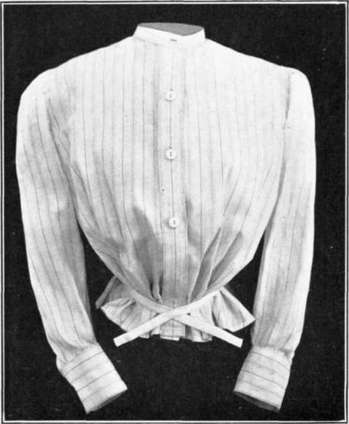

By the way, do you know what shirtwaists are? They're turn-of-the-century blouses that had modernity written all over them, the free woman's uniform -- even if she couldn't vote. Think of them as cotton Nikes. In both cases it's been convenient to forget who makes them.

For readers who disdain labor unions -- and there are good reasons to be cautious or critical -- I'd like to offer two reasonably short links. The first is an opinion piece in the New York Times written from the point of view of a Wisconsin idealist, a calm voice who taps from his state's agrarian utopian past. You recall that Wisconsin presently has a governor who is doing the bidding of smarter, wealthier, men than he by trying to crush public workers. If history's measure were moral and not chronological, Gov. Scott Walker would have to account for 146 deaths.

The second is my own piece, one among many recountings and memorials, about the Triangle fire. Do look at the photos in the slideshow, which, however riveting in themselves, should churn your guts and fasten your resolve.

The centenary of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire, the Titanic of this nation's movement for labor rights, is Friday, March 25.

Now, it's time to sing the rest of my headline...

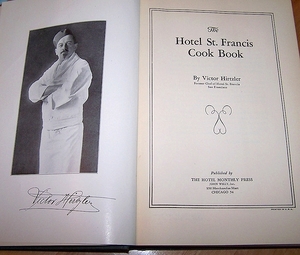

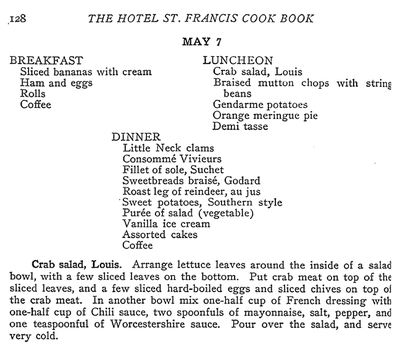

Who Invented Crab Louis?

Who Invented Crab Louis?

Take meat of crab in large pieces and dress with the following: One-third mayonnaise, two-thirds chili sauce, small quantity chopped English chow-chow, a little Worcestershire sauce and minced tarragon, shallots and sweet parsley. Season with salt and pepper and keep on ice.

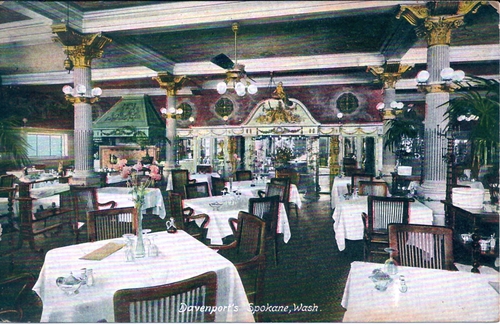

Created by Louis Davenport himself, our signature salad is made with crisp butter lettuce topped with fresh crab, hard boiled eggs, tomatoes & pickled white asparagus dressed with a rich Louis dressing.

I'm back in the writing saddle after quite some time, and it took unexpected memories of an underknown movie star to do it. The helicopter-shot hunting sequence in Tony Richardson's 1963 Tom Jones brought that equestrian cliche to mind, because in it a saddled Sophie Western is plucked off her runaway steed by a steed of another kind, the ready, randy Mr. Jones.

I'm back in the writing saddle after quite some time, and it took unexpected memories of an underknown movie star to do it. The helicopter-shot hunting sequence in Tony Richardson's 1963 Tom Jones brought that equestrian cliche to mind, because in it a saddled Sophie Western is plucked off her runaway steed by a steed of another kind, the ready, randy Mr. Jones. Blogroll

More a cracker than a roll, but 10 for the moment:

Robin Holland

Studies in Crap

Obit

Ehrensteinland

Artopia

Matthew Gallaway

David Lida

Young and Foodish

C-Monster

Pam Rosenthal

-thumb-500x299-19324.jpg)

Frederic Marschall-thumb-348x504-19130.jpg)