It's almost pink, not a pretty-in-pink pink but a sickly, Pepto pink. Neither liquid nor solid, it crawls from server to plate like lava, lava with chunks.

I know what those chunks are, because I chopped and diced green pepper, green onion, and green olive to create them.

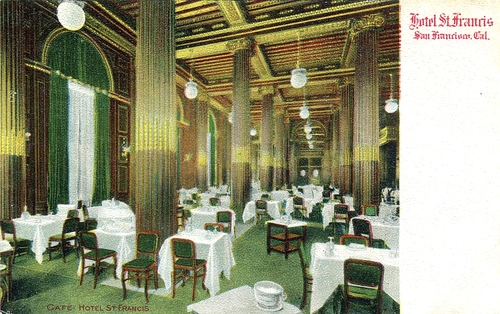

Sure, I licked that spoon. But in the time it took for my palate to awaken, before I could compute the flavor and register my pleasure and approval -- the taste was right, in the certain way that a blend of wrong things can be right -- I found myself not in my own kitchen but at a small, naperied table, dwarfed by an enormous room with tall columns and large electric globes.

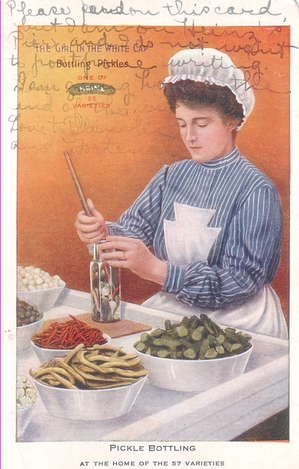

Sunlight tries to force its way through tea-colored curtains. (They look emerald in the illustration, but postcards of the time were colored fancifully.) Smoke drifts from the glossy bar, and polite clinking can be heard from similar tables around me, with muffled clatter somewhere in back.

A high, hard collar digs into my jaw. These sleeves are the roughest wool I'd ever felt, my pants the same. I touch my hair: grease. Everything is off, unreal, yet the crab salad in front of me looks like a friend because it wears the same thick, pink coat. I find myself tearing a soft roll and swiping things off my plate. Nothing ever tasted so good, nothing.

I am in San Francisco, you see, some years after the earthquake, but before we enter the Great War, finishing my Crab Louis.

Have you ever eaten or assembled a true Crab Louis, which most everyone spells and pronounces "Louie"? It's an early-modern offering whose merit and value come from the happy collusion of two centuries and two places: staid old France and nervy America. To be sure, we of the 21st century are genuinely surprised that ancient citizens ate salads. On National Public Radio we now learn that even the fecund dungeness crab, Louis's raison d'être, is finally threatened. Of course, West Coast trawlers at last century's turn returned to port with nets full of dripping pincers, so why not expect them forever?

Opportunity grew everywhere; was kitchen genius wanting? Haute cuisine chefs of yore bragged in print about using chic canned corn and bottled sauce. So which of them invented this assortment of lettuce, hard-cooked egg, and same-day crab meat with a ketchupy remoulade or what we'd now call a quirky version of Russian or Thousand Island dressing?

It may sound odd, but new recipes aren't unique, like paintings. Instead, local ingredients and culinary fashions result in almost identical dishes that pop up in clusters, simultaneously, like novel mushrooms in welcoming soil.

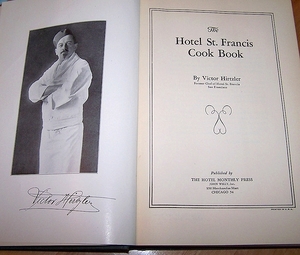

So it is with Crab Louis, for I am sitting in one of at least three West Coast dining rooms that may have served it first. You can't see me in the neutron-bomb card above, but that's where I find myself, in the cafe of San Francisco's Hotel St. Francis. Fame-queen chef Victor Hirtzler runs the kitchen, and will for quite some time.

Major digression: Some claim that Hirtzler was responsible for Woodrow Wilson's razor-thin second presidential victory in 1916. The story goes that the credible Republican candidate, Charles Evans Hughes, was to be hosted by the hotel's owners at a pre-election banquet. But right before the meal, waiters went on strike. Because the kingly cook told his guests not to worry and himself served the food, the union leafleted the city, attacking Hughes as anti-labor -- which, as a firm Republican, he most certainly was. Hughes lost California by 3673 votes, and therefore the White House.

Our megalomaniac chef with the pointy beard probably assumed that his dinner was more than adequate compensation.

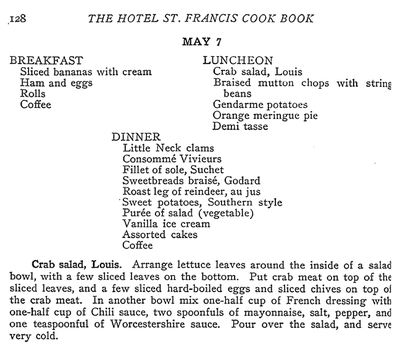

Here's the Hirtzler Crab Louis recipe, from the May 7 menu in The Hotel St. Francis Cook Book, published in 1910:

Gendarme potatoes? Glad the chef's not serving that reindeer leg on December 25, with or without the jus. You may read -- and cook, if you have cinematic ambitions -- the whole fat-laden tome page by page via an extraordinary online culinary resource called Feeding America, which archives dozens of influential U.S. cookbooks from the late 18th- to early 20th centuries.

Two More

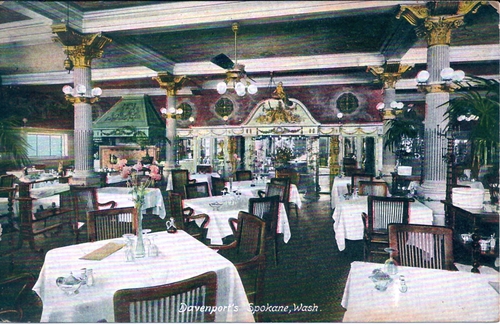

Postcards of Solari's Restaurant, at 354 Geary Street, show that it was lit by pseudo-primitive Mission chandeliers that would now bring a pretty penny. In 1914, Clarence E. Edwords wrote the peripatetic and thoroughly charming Bohemian San Francisco: Its Restaurants and Their Most Famous Recipes, in which he includes Solari's own Crab Louis -- not in the body but in the afterthought index:

Who Invented Crab Louis?

Who Invented Crab Louis?

-thumb-500x299-19324.jpg)