Out There: December 2009 Archives

First, the Monokini

First, the Monokini Constant readers may have figured out that I spent most of November far from home. In fact, I was in Los Angeles, playing with and listening to this year's fierce and frolicsome USC Annenberg/Getty Arts Journalism Program Fellows. Were I employed by one of this nation's foundering dailies or weeklies, I'd have been expected to blog at least daily about my SoCal travels. But I have no such obligation, so I'll allow my sun-soaked brain to right itself and -- what's the word? -- process, percolate, evaluate the cinematic moments and fugitive thoughts that sped by. Even feelings require time to mature, so I will wait a decent time until I uncork mine.

Potato Head

In the meanwhile, I'll respond to my scarlet disappointment over the recent no-gay-marriage vote by the New York State Senate -- yes, George and Martha, sad, sad, sad -- by offering the text to a short rouser I presented at a Nov. 22 benefit for my friend Bill Stern's Museum of California Design.

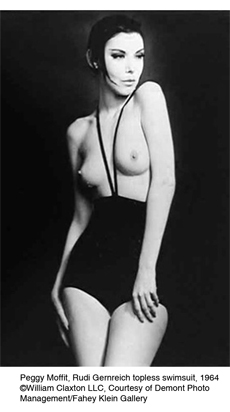

The swank hillside view of L.A. was right out of Turner Classic Movies, and the splendid afternoon honored clothing designer Rudi Gernreich (GERN-rick), a man whose reputation was simultaneously confirmed and undermined by his echt media object, the topless bathing suit -- wryly called the monokini.

At the party, Gernreich models and ageless camera-candy Jimmy Mitchell and Peggy Moffitt (Moffitt at right, center) easily bridged past and present glamor; '60s mane-maker Vidal Sassoon erased his decades with equal ease.

First, Gernreich collaborator and designer Renee Firestone spoke movingly about their creative friendship, and then I followed:

After one too many seasons of Project Runway, none of us should be surprised that clothing is design. Whether a dress or coat is good or bad design is usually thought to be determined by the marketplace -- but any one who loves the art of imagining and making things knows that's not necessarily so.

Rudi Gernreich spent most of his productive life entirely aware that clothes were ideas in material form. His innovations weren't of the "masterpiece," perfect-object type: instead, they embraced the new concept of lifestyle and -- in his soft bathing suits, body clothes and tube dresses, in his unisex "do it yourself" looks and signature, playful wit --celebrated the removal of restriction and corseting conformity.

How did Gernreich understand that a piece of clothing could somehow embody a larger sense of freedom and liberation? I'd like to suggest that it had something to do with his being what we now call gay.Of course it's dangerous to make such generalizations, and we know that creativity comes from many places in one's life. That Gernreich was a dancer must have informed his "leotard" vision of how a dressed body should float with naked ease in and around every situation.

Around 60 years ago here in Los Angeles, Gernreich, with his lover Harry Hay and others, formed the Mattachine Society, probably the first gay rights group in the country. Some later criticized the designer for not coming out after taking those amazingly brave early steps, but most of us now could barely imagine how difficult and dangerous it was to do so: you could lose your job, your friends and family, and even your life.

This is not the time for a history lecture: we honor the designer best by kicking up our heels -- by getting rid of them completely. So don your mental monokini, dust off that lavender thong. The sparkling designer Rudi Gernreich is one of my heroes, one of my gay heroes, because at a time when so many were forced to keep quiet, his clothing flung open the closet door and, with a big, loud bang, came out.

I have no obvious segue to this entry. Just take a knife to the screen in front of you, slit it open, and let the hot cloud of digital steam envelope your face.

Where's the butter?

Since I returned to the dark and damp East Coast, I have wanted to eat sluggish things. So when I saw a five-pound bag of Idaho russets, runty but firm, for a mere $2, I dragged it home and, after washing a pair and poking them with a fork, threw 'em into a 425 oven.

In 10 minutes their dirt perfume filled the house, and I swooned ... no, literally swooned. I actually hit the bed and entered a potato fugue-state.

Whenever I get off the plane in Southern California, I enter a similar state, one that transports me to my late teens and early 20s, when I went to grad school first in smoggy Riverside and then lush La Jolla. What I remember most is the way the evening air held things: a scent of hibiscus or eucalyptus, Bird Rock salt spray, dry rot plus lemon. When I inhaled those local elixers, all my New York stooping and sourness floated away. Shoes became flip-flops, pants became shorts, strangers became lovers.

And it still happens, the flip-flops anyway.

So I cracked open the slightly wrinkled skin, sucked up the steam, and without any ameliorating butter pried off a clump and placed it in my mouth. It started out right, and the time machine began to whirl, but then my food immediately collapsed. No, this was pasty failure, nothing like the baked potato of my mind.

What's changed, all you epistemologists and parsers of the past? The industrial dug potato? The taste buds and nose flowers? The way of cooking? Or have memories themselves metastasized, idealizing in ever more insupportable ways a child's potato pleasure? Though farmers and chefs will never admit their part, both sets of diminishment may be true, merging into one cheerless path.

What I miss most is the cloudy, "floury," fall-apart nature of my own private Idaho, the searing heat and fleeting texture that makes the baked spud a specific open door to my supper-table happiness. In my potato, there's none of that dull, academic wetness, the touch of almost-slime that allows new potatoes, those twee boiled balls, to remain solid hemispheres after they're sliced. Even the most tempting fried potatoes -- I will never turn one down -- are by definition coated with obstacles to their vegetable center.

Why, then, do I continue to approach my Idahos with constant anticipation? It's habitual optimism, I guess, the kind you find in present-day, beat-the-drum gay politics as well as in Rudi's old gay clothes.

There's no sense, I believe, at this stage of the game in not trying.

For an automatic alert when there is a new Out There post, emailjiweinste@aol.com .