Out There: September 2007 Archives

Cocktails and Modernity

As we slouch toward fall, here's a toast:

To the cocktail, the commonest canvas for culinary creativity out there. I'm not referring to nauseating luxe novelties such as the $14,700 martini served in a Tokyo restaurant (cited in Conde Nast Traveler) with a one-carat Bulgari diamond where the brined olive would be. That amuse-gauche had better be made with a very special gin, because it's a lot of money for a single carat. A 20 percent tip comes to $2940.

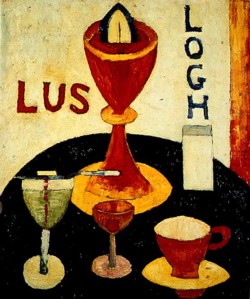

Single mixed cocktails are older than we think. Marsden Hartley's Handsome Drinks (above) was painted in 1916, which may surprise those of us who assumed the cocktail version of modernity began in the '20s, when Our Dancing Daughters' indefatigable flapper Joan Crawford, no doubt fueled by one too many, jumped on a table and nearly destroyed it with her pile-driving Charleston. No, Hartley's early slope-sided glass holding a scarlet prize looks awfully familiar: an artist's wry Manhattan.

Yes, they were drinking our drinks when skirts still covered calves, years before poet Edith Sitwell tried to condense the Jazz Age into one unsyncopated phrase: "Allegro negro cocktail-shaker." Dictionary definitions of the cocktail -- a spirit, bitters, sugar, water -- were common in the 19th century, but the term didn't enter the cultural lingo as something that meant lipstick-stained amusement and social delight at least until World War I shuddered to a close and women got the vote.

I wish I could see the transformed face of the lucky soul who lifted the first martini. Of course, one of the reasons the martini thrives (gin, not vodka!) is that, as I've written before, the first glacial sip is always a revelation, the second a verification.

Now, in high-rent restaurants everywhere, the bar is the place and cocktail the medium for innovation. Kitchen originality has been left to "molecular gastronomy," which sits firmly on the shoulders of Catalan chef Ferran Adrià and his restaurant elBulli. (The estimable Slow Food movement embraces a broader sort of social change.) Molecular gastronony is signified by liquefied solids, flash-frozen liquids, wispy froths, Euclidian shapes, quintessential clarion flavors that irrevocably divorce the stolid original ingredient from the pleasure of eating. Although this rarefied beast doesn't transport easily to Rachael Ray's Krispy Kreme kingdom -- actually, Crisco foam might be worth a try -- a new elBulli line of "natural food derivatives" is being marketed to less-than-molecular chefs, including the popular melon caviar and toothsome "lime air."

Adrià treats cocktails as if they were anything else on his menu: he takes them apart, concentrates their elements, converts them into spheres, sheets, powders and foams, and then, when natural shapes are gone, assembles the pieces. His methods have pushed edgy mixologists elsewhere to offer such potables as olive-shaped, martini-filled bubbles (the single globe at the bottom of the glass is the drink) or leather-infused bourbon for a particularly butch Manhattan. I personally prefer my Manhattans with leather-infused rye.

Those who see in molecular gastronomy a similarity to the idea-centered, synesthetic, don't-really-cook-me recipes of Futurism founder and Fascism enabler Filippo Tommaso Marinetti (Raw Meat Torn by Trumpet Blasts or Springtime Meal of the Word in Liberty, which is peppers, garlic, rose petals, bicarbonate of soda, peeled bananas and cod liver oil arranged in equidistant piles) may be amused to know that the organizer of this year's Documenta art extravaganza in Kassel, Germany, one Roger M. Buergel, invited chef Adrià to be part of it. In a press release, Buergel explains why:

This is what I am interested in, I don't care if people consider it as an art or not. It is very important to mention that the artistic intelligence does not depend of the format; we should not relate art only with photography, sculpture, painting..., neither with cooking in its most strict sense. But under certain circumstances, cooking can also be considered as an art.Really? How novel.

So, to oblige, Adrià said his famed restaurant in Cala Monjoi should be considered a satellite Documenta pavilion and agreed to give two random Kassel visitors each day "the possibility of living the unique experience of having dinner at elBulli." (I would like to believe that the regrettable tone is a result of student translation.) In case you're interested in scoring that stellar reservation, Documenta 12 runs through Sept. 23.

Please don't misunderstand. I am thrilled that attention is being paid to a process that turns sustenance into sublimity -- something that cocktails in their infancy had a leg up on anyway. Those who can't make it either to Cala Monjoi or Kassel should at least try drinks and a meal at wd-50 in Manhattan's Lower East Side and see what is meant by "pretzel consommé." For years I have tried to explain wd-50 chef Wylie Dufresne's (B.A. in philosophy) two-dimensional grisaille quilt of oysters, no longer on the menu. It not only turned the fat mollusks into a flat essence, but made a subject into an image the same way Francis Bacon painted a pope.

Years ago I asked Peter Hoffman, founding chef of New York's Savoy restaurant, how he came up with ideas for recipes. Like many curious cooks, he read, traveled, marketed, and ate in other places. But then, he said, he had dreams -- about standing at the stove, melding flavors and textures so new ones would arise.

Do dreams taste? Can you have a flavor nightmare?

Adrià gets a lot of press from his actual laboratory in Barcelona in which he and his staff spend months test-tubing the next season's menu. (Marinetti, by the way, preferred formula to recipe.) But every good kitchen, though mostly an assembly line, should be part lab. And every decent bar has the aesthetic responsibility to be the same.

So what is my list of handsome new drinks? Here's where you expect examples that might include herb infusions, steeped lichees, atomized musk. Yet I hesitate to be specific. One risk in cocktail invention is that unless a drink has an "anchor" that allows it to be ordered again and again, the new elixir can fade fast, which is why my pomegranate molasses mojito, belle of last year's ball, this summer stayed indoors. Finding that anchor can be a creator's most difficult task.

Another risk is that the most delightful personal discovery may be someone's old hat, such as when I first tasted the roseate, feminine Hearst (gin, sweet vermouth, Angostura and orange bitters), which turns out to have been served at the Waldorf-Astoria in the '30s, and the blond, masculine Gordon, which is merely gin, a thimble of dry sherry, and a lemon twist. (Because each gin is itself a recipe, the brand you use determines the result.) The elegant Gordon is an old-timer, too.

When I lived and worked in Philadelphia, I tried to invent a cocktail. It was to be traditional in style, rum-based (the city's Colonial history would have it so), a simple refreshment with the suave inevitability of a Manhattan. The Philadelphia. Some of my messy experiments came close, but nothing ultimately claimed its glass. Is there an artist- or writer-version of drinking one's failures?

Just like any other art form, a bad cocktail leaves one shaken, a great cocktail leaves one stirred.

Footnote: I can't omit DrinkBoy. Robert Hess's site foresaw the cocktail comet; DrinkBoy also links to other worthies, including cocktail artist Dale DeGroff and the Museum of the American Cocktail (guess where it is).

For an automatic alert when there is a new Out There entry, email jiweinste@aol.com.