Yeast isn’t a food or an ingredient, except in tiny ways. It plays on food, like a conductor, or a cook. So when you realize that yeast floats in the air and lives forever, or almost forever, you may have more respect for its governance, its fungal baton.

A random search engine found an article that had the word “Holbrook” in it, Holbrook being not an actor but a hamlet — yes — on Long Island, New York, where my beloved Costco sits, 20 minutes by car from the St. James Brewery.

Low-ceiling industrial malls don’t magnetize shoppers, but St. James set up in one because it needed room to brew. Associated Press recently posted more than one piece about St. James brewer and sea diver Jamie Adams, who, with a team, recovered motley bottles — probably of a Bass barley wine — from a somewhat glamorous British passenger liner, the SS Oregon.

Speed-demon Oregon, which held almost 1500 windswept passengers, went down in the Atlantic on March 16, 1886, approaching its berth in New York City. Everyone was saved, in case you were worried.

The Oregon sank not far from the coast of Fire Island, now a resort sand bar that has many bars. An errant, unidentified schooner had smashed a hole in the pre-Titanic’s hull.

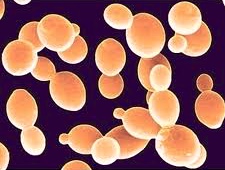

Adams and staff fussed with the intact bottles that still had gunk in them and sucked some out. After Petri dish breeding, they settled on a long-dormant but assertive strain of yeast to ferment both a “local” IPA, Fleur de Lees, and an ale they named Deep Ascent.

Deep Ascent is not the first shipwreck brew. Last year, yeasts from bottles on the Sydney Cove, a merchant ship that sank off the coast of Tasmania in 1797, were tweaked to make The Wreck — Preservation Ale by Australia’s James Squire brewery, which writes that the Wreck has “hints of blackcurrant, a splash of spicy yeast character and a wisp of smoke.”

Fleur de Lees, brewed with both the submerged yeast and an earthbound Belgian that could be older, as well as Long Island hops, is surprisingly rich and heady, without berry innuendo, but maybe a touch of caramel (perhaps the yeast-belch called diacetyl) that is sometimes considered a flaw. It’s fine here.

I’ve not tried the newsworthy Deep Ascent, made with only the rescued stuff, because the first batch is gone; another is brewing. Although a spectrum of yeasts excretes various flavors, there’s no palate way I know to tell that either brew is “old” underwater beer.

Any bottle or can left open for a day is old.

First time I served and explained the curious Holbrook IPA, I heard “ugh” jokes — until it was tasted. Were my scoffers thinking rotten corpse, or just about the blotched surface of an unknown soldier in the back of their fridge? Eating old things makes people upset, in their minds, not their mouths. But everything we eat is old, which I learned when I was a biology major. The freshest tomato, like the one I bit in my backyard when it was still on the vine, has Ancestry.com in its juice.

Some organisms survive by building shells, just like humans. Others find other ways. Particular sourdough starters or levains, which are microscopically throbbing blobs of yeast and flour, have been fed like pets and passed along from 19th-century snowbank to refrigerator for generations, but no one says ugh to the hoary loaves that result unless someone can’t bake. There’s a line in a song about everything old being new, but yeast is neither. It continues.

Then there are mouths that want to know, really know, what things tasted like eons ago.

Some little one near the bullrush Nile bit into a firm but yielding plum, dotted with rain, mottled. Without warning, a tingling coursed from mouth to where … gut, brain? It’s hard enough to figure how our young encompass what they eat. But children then? Slower or faster, despaired for or assumed?

If thoughtful, what thoughts?

The oldest record of olive oil in Italy is residue staining a chic ceramic jar, broken into hundreds of pieces, dug and gathered in Castelluccio, Sicily, from “the end of the third millennium B.C.”

“Pineapple,” my own sure taste of it, is what the ancient child could be storing in his or her hunger and pleasure memory to mark that pubescent plum. Or yesterday’s seemly “peach.” We have no way of knowing what went on as our fantastic ancestors chewed, beyond diaries and narratives, which have their own independence. But eating, more than almost anything I can think of, denies direct description: read recipes or restaurant reviews, and you’ll see how smartly the best writers twist and turn when it comes to flavor. A vocabulary of taste is narrow and self-referring, in the way “fat” is “fatty.” Does everyone taste — perceive, react to, go to private animal places — the same things differently, or is the garlic mashed always an equivalent that potato-eaters slide down and smile about, in imaginary dining unison?

Israel was crushing oil from olives at least 8000 years ago, a discovery that used the same logic, which means only a ghost of oil was left. Archeological consumers want to know which was a better shopping value, and were the jugged oils doctored with dicey product from Tuscany or Syria? All I wish to figure out is how these olive oils were regarded, went down, and if there were any happiness in them.

Those few of you who have plucked an olive off a tree, you must have some sense of the continuity of flavor and nourishment. I’d love to sip a wine older than myself, which in my case becomes ever more difficult and expensive. How could I not ask how far it would carry me back, to let me see what else is there.

Lovely. That Lede! The wordplay! The cheering idea.

Thanks so much.

Good cheer is important. So is “time travel.” Thanks, Avery

“Don’t worry, no recipes”? I like recipes, But a great piece in every other respect!