Roberto Bedoya has asked some amazing questions lately, all designed to interrogate the concept of whiteness in the arts. He’s asked a few bloggers to think about the questions he has raised and write back (so watch for posts in the coming weeks on Jumper, Createquity, Barry’s Blog, Engaging Matters, Museum 2.0, etc), and this is mine. Or at least my first attempt.

Before going into it though, I think it’s important to say that I feel a little like a lamb in the woods on this diversity stuff, not so much because I am innocent to the effects (or causes) of casual racism as because I was naïve about the extent of the issue. As I continue to delve into this data, much of which (at least in relation to race—other forms of diversity, which I’m also looking at, are not really touched on here) paints a picture where whiteness, this giant mass that surrounds almost all institutional arts presenting in the US today, should be excruciatingly obvious, and is instead so large and ever-present as to become invisible, like air.

I am afraid that I find myself, as I work through some of this information, losing my words at both the monumentality of the problem and at the systemic nature of the disparity. It has me asking all sorts of questions about will and form—are we really so stubborn as to not change? What does “change” mean, and would it actually make our art more appealing to these large swaths of people who aren’t coming?—and about time, and energy, and coordination, and money. Like all clarity, or partial clarity, seeing the true weight of the whiteness in the arts, illustrated in numbers and graphs, analyzed and parsed, is both exciting for its inherent opportunity and terrifying for the scope it reveals. Where the air is cold and thin, and the wind pushes the clouds away, you can suddenly see all the other mountains you aren’t climbing, and you can fall or you can fly.

Weighing Whiteness

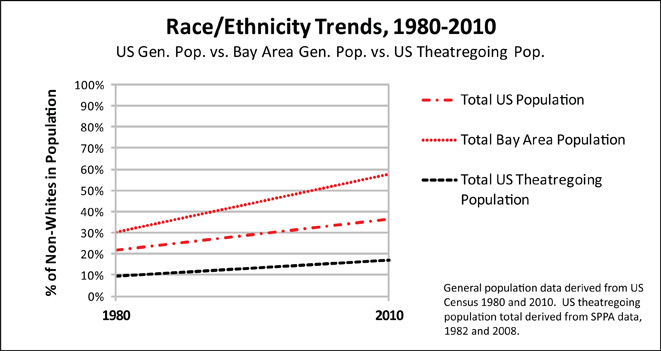

The weight of whiteness in the arts is about 15 percentage points. It only weighed about 10 percentage points in the early 80’s, but now, well:

This is a comparison of the percentage of non-whites in the general US population (wide-dotted red line), the general Bay Area population (narrow-dotted red line) and the US theatergoing population (black line) comparing 1980 to 2010. That black line is weighed down, depressed below the general population, slowly diverging from it further over time, by the weight of the whiteness of our theatres.

It’s a stark picture, I think.

Here’s another:

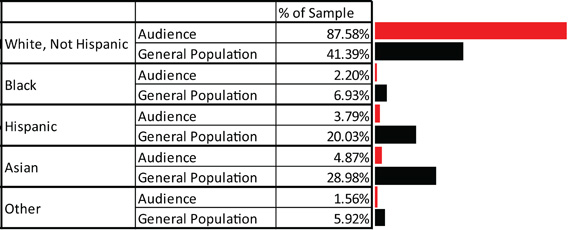

This is a comparison of aggregated demographic data on 532,000 theatre attendance records in the San Francisco Bay area spanning 2006 to 2012. This data comes from 25 theatre companies, 137 total seasons. The theatre companies range from LORT houses to under $150,000 per year annual budget, present all types of work, and are distributed among 5 Bay Area counties.

The table shows, in red, the average racial demographics of the half-million audience records, and in black, the average demographics for those 5 Bay Area counties per the 2010 US Census.

In this case, the weight of whiteness is 46 percentage points.

I’ve got to say, going into all of this analysis, I didn’t think it would be quite this bad.

One more:

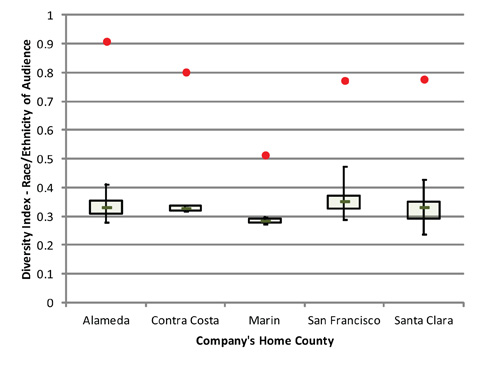

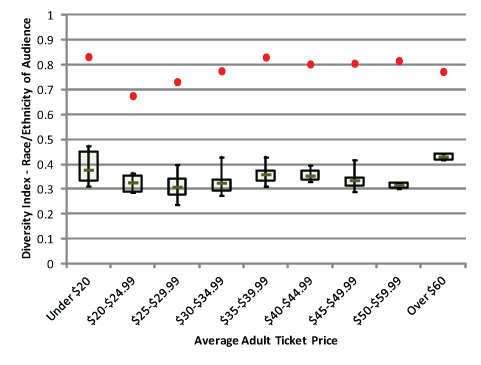

This one does away with percentage points and converts it to something I’ve developed called the Arts Diversity Index. It takes the relative diversity (in this case, race/ethnicity diversity) and converts it into a standardized score where 1.0 is as diverse as possible (which is to say, complete parity) and 0.0 is as homogeneous as possible (which is to say, only one race). The green bars are the average ADI scores for each county’s theatres in the study, with variance indicated by the boxes and lines. The red dots are the ADI scores for the general populations of each county using US Census figures. The only place we’re coming close is in Marin County, and then only because it’s so relatively racially homogeneous.

Giving Whiteness Context

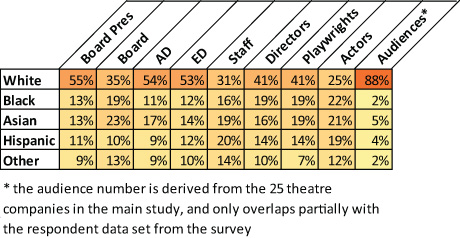

As a corollary to this data analysis that forms the core of the report I’m writing, we also surveyed our theatre company members in the Bay Area to understand what the diversity of their boards, staffs and artists were like. To date, 54 companies have provided data on their boards, staffs and artists for the season ending in 2012, with the following results:

While it is difficult to make any definitive conclusions because the audience data is drawn from a different sample of companies than the rest of the data, this information is encouraging and discouraging at the same time. On the encouraging hand, the percentage of white people serving on the boards, staffs and shows of the survey respondents is actually below the percentage of whites in the overall US population and, in most categories, close to on-par or below Bay Area percentages. On the discouraging hand, despite these great numbers, audience data indicates we’re still seeing an absolutely staggering lack of diversity all the same.

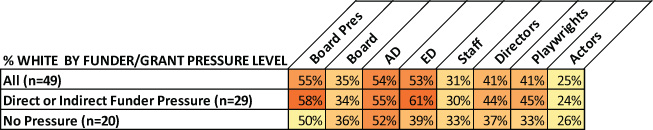

Interesting, and apropos of Diane Ragsdale’s post on coercive philanthropy, we asked these companies whether they had received direct or indirect pressure from funders via program officers or granting guidelines to diversify. When filtered to reflect those that had versus had not gotten pressure, here’s what the table looks like:

What strikes me about this table is how close the percentages are. The pressure, when it exists, exists in companies where more of the board, staff and artists are white (generally). Regardless, and with a caveat that further study is really, really necessary here, the diversity of the people making the art doesn’t seem to really get reflected out into the seats.

What Affects Whiteness?

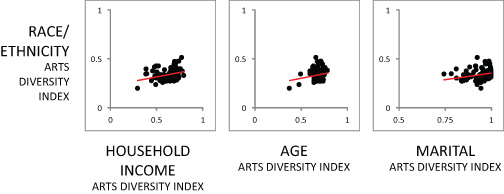

So what does affect whiteness? As part of this research, we cross-referenced the audience numbers with the California Cultural Data Project (as well as with the other types of diversity we were looking at), and found some interesting correlations.

(For the sake of this blog post’s legibility, I’m going to spare you the p-values, but all of these relationships were determined to be statistically significant. It’s also important to note here that correlation and causation aren’t the same thing—we can’t say that more differently-aged people caused there to be more racial diversity—but what this basically means is that where one was high, the other was high, too.)

– Racial/ethnic diversity was positively correlated with:

- household income diversity

- age diversity

- marital status diversity

– Racial/ethnic diversity varied in statistically significant ways based on:

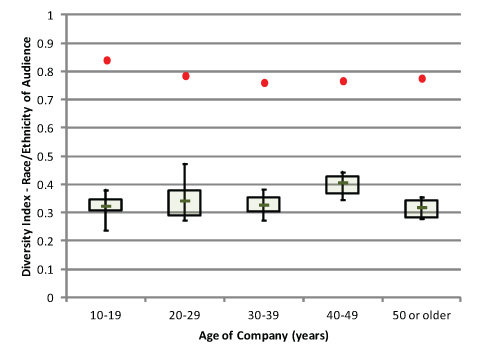

- the age of the company. The older a company was, the more racial diversity existed (though as you can see below, this difference was marginal at best—but still statistically significant).

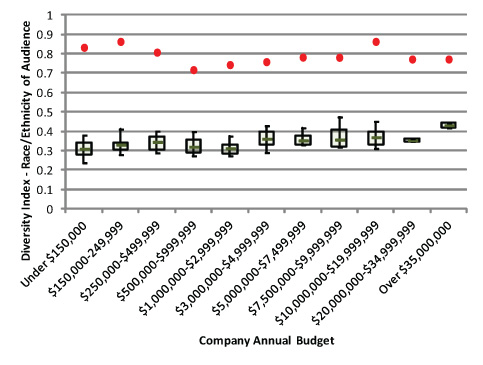

- the size of the company’s annual budget. The larger the company was, the more racial diversity existed.

- the average ticket price. Very cheap and very expensive tickets yielded more racial diversity than in between.

So, What’s That All Mean?

Well, honestly, I’m not sure yet. But what it provides, in a way, is a lot more specificity about where the meager amount of racial/ethnic diversity that does exist is coming from. Company budget size is highly correlated with age, which basically means that the larger companies within this study, probably more by virtue of being more known and more “mainstreamed” to more people, demonstrate slightly more racial and ethnic than smaller companies. While increased racial diversity correlating with marital status seems somewhat random to me (I need to think about that one more), the fact that it correlates both with age diversity (which, in this sample, is the same thing as saying “more young people”) and household income diversity (which, in this sample, is the same thing as saying “more less-wealthy people”) makes sense—we know that younger people generally are more diverse, and that both younger people and non-white people are generally less financially well-off.

It’s interesting to me that we only really see increased racial diversity among the very cheapest tickets, and then not again until the largest category. It says that the idea of discounting may only work when you’re talking about a price that is untenable to a company of any real size.

Which is all to say, the goal of this report isn’t to necessarily provide all the solutions. It’s to give people a hard, data-driven and statistically tested baseline from which to start a very complicated conversation. I’m pleased that the blogosphere is carrying forward with it, and I hope very much that once the report is out there in the world, arts communities across the country will engage with it as well.

“we know that younger people generally are more diverse, and that both younger people and non-white people are generally less financially well-off.”

Part of the reason for that is that there’s a Demographic Racial Gap emerging in the the US. The proportion of the White population of the US is aging much faster than the overall population which is going to create some systematic economic disparities. As the NYT link above notes:

This is going to have profound implications for what Waldfogel calls preference minorities.

Clayton,

Another critical piece of this is to understand that all theaters can’t necessarily be all things to all people despite the serious efforts by many theatres to be operationally affirmative in their governance, hiring and programming. An important statistic to be added to the mix is the number and relative health of the majority minority theatre companies, eg those with boards, staff and or artistic visions/programming that are non-white. Do we know that number? . And do we know their financial health and what percentage of the aggregate budgets they represent? And whether they are in substantive partnerships with other theatre companies or historically white cultural organizations? Or partnerships with funders rather than arms-length grant making relationships? This sector of the landscape is critical to advancing a robust, diverse field. Because these groups have a commitment to and expertise in CONTENT that will broaden and deepen audiences. It’s not just how and why, it’s who and what.

I agree with Margot that better and deeper knowledge of the culturally specific sector of the arts community is key to advancing pluralism in the arts and arts audiences. I’m part of a research team at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago that is working on developing and gathering information on this sector as a pre-project literature review revealed little current information on the numbers, financial health, or partnerships of these organizations. Our project maps the culturally specific sector, including information on needs and collaborations. We’ll be releasing our report within the next year and hope that it will assist the arts community in broadening its frame of reference in these discussions.

It might also be useful to examine more regionally specific numbers. For example, blacks comprise only 6.93% of the Bay area as a whole, but 35.66% of Oakland. How much theater does Okland have and how well are blacks represented in them?

Thanks for all of this work, Clay. I confess, I need to spend a lot more time decoding the presentation of the data here, but it’s nice to have some basic pictures of the current environment.

I wonder if there’s an overlay you can do that deals with programming– not just whether the programming is “diverse” in the sense of reflecting stories of diverse perspectives, but also who is making the programming decisions. I don’t ask to diminish or distract from the stuff you are already focused on, but in my experience the frame of whiteness that surrounds programming– both the selections and the process by which those selections are made– is largely intact today in the institutions in this study, even as outward efforts to show color in staffing, board, and audience yield some level of measurable (and visible) results. Mr. Bedoya talks about assets and who’s controlling them. Programming opportunities, marketing dollars, engagement priorities, and the venues themselves are all assets that are essentially locked inside the whiteness frame along with capital and so, almost no matter what else we accomplish, we’re not moving the needle on the frame in this sector in any significant way.

I have been slow to wade into this whole discussion for some of the same reasons you list. I lose my language. I quickly get over my head. I have only my direct experience to draw on and it’s entirely colored by my privilege and the history of my personal priorities over my career. But I do know that for myself there’s a basic disconnect between what I encounter on a day to day basis as I try to work toward a more relevant? impactful? ethical? responsive? theater and the frame of much of this discussion around diversifying the audience. In almost every circumstance among the types of organizations in your study, the efforts are anchored in the same frame that delivered the results in the first place. The relationship between the institution and the audience is the same, just the target population has changed. The relationship between the programming decisions (made by the leadership of the institutions then foisted on the target population) and the communities being targeted remains the same. The manner in which the programming is delivered and marketed is both determined by the keepers of the frame and delivered through the same mechanisms with the same messaging.

I am a person who learns by doing. This has its limits. I am certain, for instance, that if I were a person who learned through study of what others had already done I could avoid some of the mistakes and lost time that I have experienced throughout my life in theater. And, if I learned by study, I would be able to generalize more than report out from my personal experience. But it is where I am and I am doing what I can.

In my personal experience, it is very hard to actually shift the frame itself in all of these dimensions. Programming, for example, for it to be something that actually proceeds from something other than the given frame of “we, on the artistic staff, have surveyed the available work and have decided that these plays are the ones that you want and so now we’re asking you to come see them”, needs to flip the current power relationship between the audience and the programmer. I have been listening closely, of late, to a number of different voices in Boston’s diverse African American communities and I can tell you that the things we (the programming staff) presume our neighbors want to see in our theaters are neither constrained nor described by the narrowness that infects our assumptions. Similarly, the difference between our staff-derived assumptions about how to invite different communities into our work and the meanings conveyed by these staff-driven strategies around the invitations is eye-opening if you ask and listen. I am both amazed and grateful that my neighbors have engaged me in this inquiry, despite the decades of evidence that it is unlikely to yield any lasting and fundamental shift.

I won’t weigh this thread down with a bunch more on this topic. Just wanting to say that, for all the great work going on here around analyzing the current results, the real challenges seem to me to be embedded in the frame and not the efforts– as others have been pointing out forever the basic relationship between the institution and its neighbors is, in its essence, one created by, for, and from the perspective of white habits and priorities around culture. And discussions about “butts in seats” that are working inside that frame are, to some extent, rearranging deck chairs.

You asked in a Twitter post following Mr. Bedoya’s March 6th post: “What do we do now?” I think that’s the place to start– and that the question needs to be directed outward, toward our neighbors, and we need to be prepared to listen to the answers. Mr. Bedoya points us at “We the People” as one possible starting place. I can work with that.

Clayton

Clayton,

Thanks for this post and your contribution to this investigation into whiteness. This portrait is important information and necessary to know if one wants to address the cultural disparities in the field. How one uses this research, how one make the arguments to craft the policies in response to “shape of whiteness” that you point out is an important next step. Thanks again for the post and your contribution to the discovery phase of this mutual undertaking.

Best

Roberto