Before I knew her, Tina, one of my best friends growing up, was made to stand in front of a room full of her white elementary school classmates on a Connecticut school day. In an effort to teach children about race, the teacher instructed the white kids, all sitting behind their desks, to look at Tina, who was Korean, standing in front of them, and to point out the things that made Tina different. She did not then put a white kid up there and afford Tina the same opportunity.

Before I knew her, Tina, one of my best friends growing up, was made to stand in front of a room full of her white elementary school classmates on a Connecticut school day. In an effort to teach children about race, the teacher instructed the white kids, all sitting behind their desks, to look at Tina, who was Korean, standing in front of them, and to point out the things that made Tina different. She did not then put a white kid up there and afford Tina the same opportunity.

I think about this story sometimes, which Tina sobbingly told me some time in high school, as I watch my daughter, whose birthfather is black, interact with the world of her two white dads. We did not expect Cici to be half-black; the picture we saw of her supposed birthfather was of a large and woodsy-looking Irishman, flaming red hair and beard, green eyes, skin like paper. When Cici came out, she was all red from the birth and then yellow from jaundice, a mop of black hair and flattened nose the only indications of what would eventually be revealed to be the truth, and for a while Seth and I, exhausted and overwhelmed from the experience of becoming new fathers, chose to believe Cici’s birthmother’s explanations that Cici had apparently just picked up a strain of Black Irish genes from the far side of her family. Cici’s eyes, then, were blue, and Jake Gyllenhaal kept floating behind my eyelids, so I let it be believed.

This all seems so silly now, both our denial of the reality and what I now see as an anxiety that she might not just be white. As I watch her play, so beautiful, her curly hair a perfect synergy of her races, her skin like caramel, her nose still centered on her face but now far from being the only thing that might show her mixed heritage, I very rarely notice the differences except in moments when I am thinking about how to care for them. We have carried forward over the past two years, stumbling and bumbling as she has become a young toddler with more cognizance of her world, to ensure that it is not as white as we discovered it to be when we looked through her eyes.

What I have learned is that I didn’t know how monocultural my world was. I apologize to any readers of this who aren’t, you know, white and male, who find this particular revelation laughable–I get how obvious it may be, even as I hope you understand how surprising it was. This monoculture, of course, holds no malice–it is simply the manifestation of a particular gravity that Seth and I now find ourselves pulling against clumsily, cultivating in Cici a love for Princess Tiana, integrating books with multicultural heroines into her overflowing shelves, preparing ourselves to think about what it will mean for Cici to become aware of her blackness in our household.

I am a WASP to my core, always searching for placidity, always folding up blankets and putting back toys at night, always fighting against entropy. The indelicate intentionality of our efforts at diversification, the blunt-force nature of it, the fake-it-till-you-make-it-ness of it, pushes against my natural impulses. It feels obvious and pandering and clumsy, but we do it because that’s how we learn to walk, clumsily.

In his essay “Notes from a Native Son,” James Baldwin talks about discovering “the weight of white people in the world.” I don’t think I really understood that quote–that whole essay, really–until we got Cici. The pervasive weight of our views was not apparent to me until we were required to pull against them, the inertia that such weight engenders unclear until we attempted to change direction. We carry forward in a mighty, invisible tide, so cozy as to only be apparent when you try to turn to shore.

It is at this same moment that the arts find themselves now.

“Should an arts organization that finds itself located in a more diverse community be expected to serve a more diverse audience?” I asked that question yesterday on Facebook and Twitter, where it started some very interesting conversations. Three times it was called overly simplistic or disingenuous. It was not meant to be, but I take the point. When pressed on the nature of the question and why it was problematic, those I was corresponding with stretched back to questions of mission, of the particular idiosyncratic nature of each organization, and of the danger of proscriptions like what I was proposing without taking into account the particulars. I take that point, too.

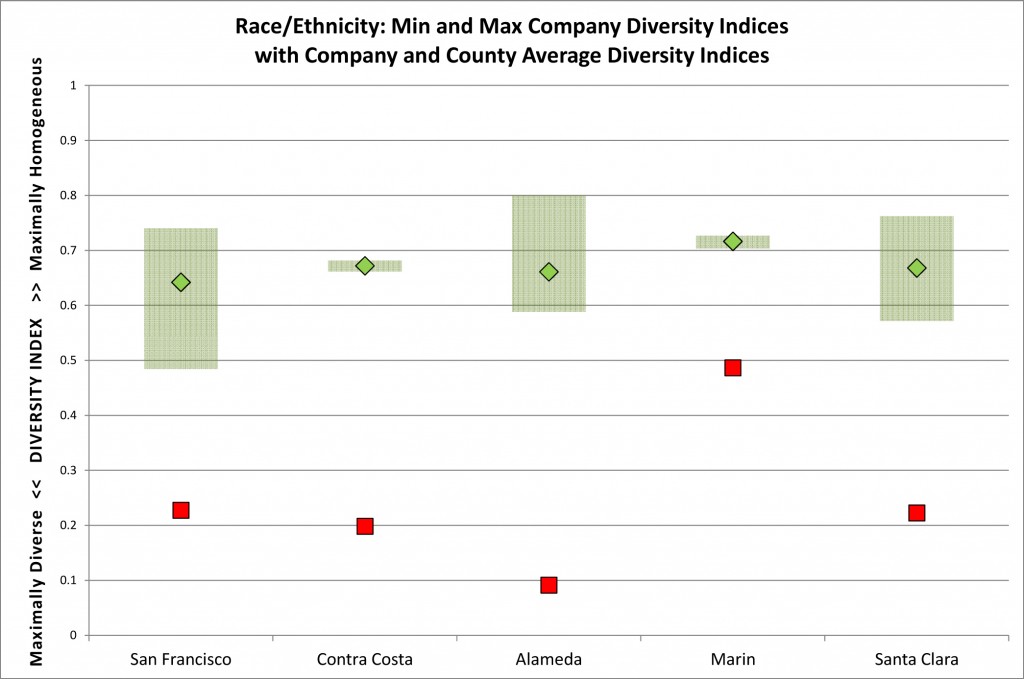

But I asked the question because, as I continue to evaluate data for this forthcoming paper on the diversity of Bay Area theatre, I have been struck strongly by the homogeneity of the cohort, particularly when it comes to race. It should be said that among the 25 companies I am looking at there are no truly culturally-specific theatres (because they had insufficient information in the various data banks from which I pulled to take part), but it should also be said that these companies do represent a strong cross-section of the type of work, structures, and sizes that make up the majority of the nonprofit theatre system. They have differing missions, they exist in differing places, they do demonstrably different work, and yet when you graph their race/ethnicity diversity indices against the average US Census populations of the counties in which they perform, this is what you see (click for larger image):

In this graph, the green diamonds are the average diversity index scores for the theatre companies in the study who perform in that county. The scores have been normalized, with maximum diversity sitting at 0 and maximum homogeneity sitting at 1. The green bars behind the diamonds show the spread–the maximum and minimum index scores achieved by any organization in the cohort. The red squares, down towards the bottom, which is to say in an area that indicates markedly more diversity than the green things, are the diversity indices for the counties using data drawn from the US Census.

There is basically no difference in the level of diversity among the theatres’ audiences across counties at all, even in the counties where the actual total populations are majority-minority. More than that, in all counties even the best diversity score is still far from the county’s general population. On average, these twenty-five companies have audiences that are over 80% white in one of the most diverse regions in the country.

As one marketing director at a company in this study said to me, “Why is it useful to tell us what we already know? Do you think we don’t know we aren’t diverse?”

No, that’s not what I think. I think we know we serve a whole lot of white people, just like we know we serve a whole lot of older people, a whole lot of very educated people, a whole lot of wealthy people.

Last week, I wrote about “valuing” versus “managing” diversity. This is a perfect example. When I asked that question about whether companies in more diverse areas should be expected to have more diversity in their audiences, the answer was almost universally, “Yes.” We value diversity almost universally.

We get it, abstractly, the same way I understood that, as ambivalent about race as I was, as liberal as I was, I still wasn’t really ever around people who weren’t white, and that that might not be the best. But it is not enough to simply understand the existence of disparity, we have to be willing to actually do something. We have to understand the reasons why we can say “Yes” to my question and yet still make no functional movement forward on changing that.

The inertia of whiteness is strong and pervasive, which makes the problem relatively easy to identify and very difficult to consider tackling. The monoliths that are our older, white, wealthy subscribers, many of which directly prop up our organizations and without which we would horribly destabilize, make thinking about the people on the other side of that monolith difficult. The conscious effort required to attempt diversification, just like the conscious effort required to think about searching out new black friends with kids–a prospect which feels artificial and utilitarian, and which requires me to confront the laziness of my white reality–is tiring, even moreso for the fact that the benefits, if there are any, won’t be reaped for a decade or more while the discomfort begins as soon a you take the first step.

I get all of that. But let me suggest that we start here: when I ask the question “Should an arts organization that finds itself located in a more diverse community be expected to serve a more diverse audience?” do not immediately push back on me with a discussion of mission. Do not immediately pull out culturally-specific arts organizations and how it would be unfair to ask them to dilute their missions. Not to be indelicate, but do not suddenly be concerned for the welfare of the few organizations in our ecosystem that are functionally trying to get the art we love to people other than us, and that are given less attention (undeservedly) in almost all circumstances than their mainstream (white-serving) counterparts.

A mission is a driving principle, not a shield. Unless your mission is “we make art for white, old, rich people,” that pain you’re feeling at the thought of diversification isn’t mission-based, it’s bottom line based. A mission should not allow a company to opt out of serving a wide array of people unless the mission is to only serve a narrow range of people–which is, to point it out, decidedly not the mission of any of the twenty-five organizations in the study.

The art we make is local. It is place-based, which means it is community-based, whether we want it to be or not. As Catherine Michna points out in her wonderful essay on avoiding gentrifying art, bussing a bunch of white people into the Ninth Ward is not the same thing as serving the people of the Ninth Ward. Fundamentally, a graph like the one above, where our theatre culture is just a large white smear across a canvas of many different varying shades of beige, is wrong, and is exactly reflective of the endemic problems of our field.

We are now, I would argue, past the time of “not my problem.” We will have an easier time changing direction if we all put our backs in to it, don’t you think?

Part of me just wants to say “I love this post” and leave it at that. But I will add a thought or two. The arts, like a lot of industries, has a hard time grappling with history. The audiences we have, love them or hate them, isn’t an accident. It’s an outcome of a series of decisions. New outcomes require new decisions.

We should also be honest about how fear plays into this. When you confront a lot of organizations with the simple reality that the world is changing but there organization isn’t, you tend to scare the f*ck out of them. The core of the fear is that if they bring in “new audience” (by any definition) the old, white, audience will leave. And to me that’s the real tragedy of this thing. We think very little of our audience. We assume that just because this audience is older and white they are fearful of change and will abandon ship at the first sign of progressive movement.

We support this fear with stories. We pass around complaints from patrons, even if it just a few of them. If a Board member complains then everybody freaks out. We turns these small fears into a wall that is (somehow) supposed to protect us from a society shift toward inclusion. There is another choice. We could look at examples of industries (of all types) that are working hard to embrace diversity (in all forms). Artistic leaders could embrace the idea that these different audiences are a key driver toward the artistic freedom they all say the want.

The truth is that this crazy, complicated world represents the last (and best) opportunity for many arts organizations. They could use the high rate of societal change as a reason to move forward fast. They could invite their audience, old and white as it may be, to be a part of their journey. And yes some of them will opt out, but some . . . maybe many . . . will stay. They are the base for the new thing.

It’s probably human nature to assume that everything was better back in the day. But I see the future as very interesting and I’m excited to see arts organizations embrace it. Those that don’t will die a slow death. And that’s how it should be.

Beautiful post, Clay.

I wrote a post (http://museumtwo.blogspot.com/2010/07/what-does-it-really-mean-to-serve.html) a few years ago in which I noted that “most large American museums are reflections of white culture.” I didn’t expect that to be a surprising statement, but it sparked a Huffington Post interview with an artist who was interested in the basic question of whether museums are “too white.” (http://www.huffingtonpost.com/max-eternity/is-your-museum-too-white_b_690276.html)

I think the answer is: obviously. And we have to confront it in all the ways it manifests, overt and insidious. One of the most revealing parts of the initial post I wrote about a fabulous teen program at a science museum in St. Louis was a comment that came in:

“I used to work at the Science Center. If only the teens would act respectfully and pull up their pants, the rest of us would be just as pleased with the program.”

It’s amazing how much “the inertia of whiteness” can make us feel self-assured in expressing the most intolerant perspectives.

In 20 years we’ll all be tan … things are evolving on many fronts, albeit at a snail’s pace.

Kindly speak for yourself. Thank you! Some of us always have been “tan,” and Black, and Red, Brown and “Yellow.” And we and our families have paid – and STILL PAY- so many de-humanising prices. These facts matter. Your speculation (cause that’s what it is) isn’t all about what you think YOUR “we” “will be” in “20” years. A hundred plus years ago, my great grandfather and his siblings were mixed-race people in western North Carolina and East Tennessee. That did not spare his life when he was killed in Chanute, Kansas, on March 13, 1913. The past 500 years in the Americas, which benefitted (and continue to benefit) Europeans in dozens of ways, will be fully acknowledged, and THIS time from the experiences of those of us “on the bottom.” The harms assigned and enforced – over these centuries by both law AND “custom” – in the Americas, and elsewhere- these shall be healed, regardless of who else may, or may not, get a so-called “tan.”

I’ll also note that the Oakland Museum of California explicitly stated during their multi-year transformation that one of their prime goals was for their visitors’ demographics to grow to match those of Oakland itself. It would be interesting for you to connect with them and see what progress they have made in this regard.

This a very thoughtful and informative post, I look forward to seeing your coming research. I think a hard look needs to be taken at the basic infrastructure of theater, especially big NFPs, to my mind it is the structure of theater, much more than the subject matter that stands in the way of greater diversity. I wrote a blog post about this after reading your piece, linked below if you care to check it out. Thanks for writing this. http://www.spotlightright.blogspot.com/2013/02/why-non-profit-theater-will-never.html

Provocative and articulate essay, thank you!

Having been a part of a major cultural institution I find the difference between actually serving the community vs actually serving the donors/subscribers might best be viewed as conditional vs unconditional love. IF you buy a ticket, come washed, don’t raise your voice or speak out of turn, know something about what you’re going to experience we’ll welcome you into our home and share our love/art with you. Unconditional love declares that we accept you for who you are, and no matter what, we’re going to patiently but excitedly come to you, respectfully include one or two of you and explain to you how you could discover beauty and empowerment in life within the art/love we want so desperately to share with you… FREE!

It takes a special and perhaps very small organization or entrepreneurial, teaching artist to make such unconditional commitments. The large ones have too much at risk. Volunteerism has been the only way to bridge the chasm. It is a priceless experience to be a successful teaching artist but often a shortlived window as well. My suggestion is that organizations employ and empower such artists to be ARMS that EMBRACE their communities (large churches may work best) in their urban neighborhoods. Don’t think of it as outreach but IN-reach… because building on what we have inside changes us as well as the community.

Clay, I am working on a report for the greater Boston/NE community on diversity, inclusion, and gender parity. The report is the result of a series of conversations we had last fall, and the goal of the report is to help build some strategies for our community as we move forward. This is the beginning, not the end, of a process.

This is, as you suggest, a very challenging conversation. And one that our well meaning, empathetic, generous community struggles with on so many levels. And while I can understand the push back (to a degree that is decreasing daily), here’s the thing. We have to fix this. The arts and their impact are too important. I see our struggles as similar to the struggles of the Republican party right now–too white, knowing we need to change, with a strong belief system that tells us that we are right, which makes systemic change very difficult.

I look forward to reading your report, and to sharing ours.

Hey Clayton—thanks for the honesty of this post

All good inquiry

on a non arts tip…my family is from Alabama

I have family members that are very dark skin with bright blue eyes

One of my family members actually has gold looking eyes with bone straight natural hair

the genes of humans are amazing!

I also have a nigerian friend who has red hair and blue eyes—no european blood in her family at all…

So, looking at facial features and other physical traits is not a determinate of race, as i am sure you know…

these conversations are so very important…thanks for sharing

Very thoughtful post, Clay. It is always interesting when life changes and brings new situations into our lives that were not there before. I completely understand your basic argument for serving the community. I think we need to get to the next question and completely kick the elephant into the middle of the room. Since we all seem to value the thought and need for diversity, why are we ourselves not working on becoming more diverse?

Is it fear? Is it the fact that many of us do not know how to diversify our own lives? Or are we just too comfortable with who we are at this moment? Sometimes it takes that change in our lives to challenge our current value system.

We will not be able to expect any changes while many want to remain who they are today. The mission statement argument is a reflection of this truth. People want to be who they are, and until people want to grow beyond that, there will be no leaps and bounds changes. If it is a group of white people running the productions that are true to themselves, it is likely that they will attract a majority white audience. In order for this scenario to be different, not only would they need to change and diversify themselves, they will also need to diversify their company or at least form collaborations with other groups within their community.

A last point I would like to make is that when companies (and people) do make the changes, or if new companies sprout to take on the challenge of serving these diverse communities, I feel if managed properly, they will see the majority of the audiences and artistic growth.

In the end, we can’t expect people to be different and take on the desire for diversity, but here’s hoping they will want to in the near future!

I’m not sure where to start with this post (or perhaps more to the point, where to end), so I apologize if this comes across as muddled. Rather than getting all meta on the anxieties about race and privilege expressed above, I’ll instead focus on your call to action, which brings up some important philosophical issues that I think merit further examination.

Is it “wrong” for an individual theater to have a mostly white audience, if its mission is broad and its community diverse? You declare it to be so, in no uncertain terms. But I’m not so sure. I think we have to accept that certain genres and artistic traditions, for all sorts of reasons having to do with social history and notions of community identity, are going to resonate more for certain cultural groups than others. And since “educated white people in the United States” is a cultural group, albeit a privileged one, by nature there are going to be types of programming that appeal more to this audience than they do to others.

Sure, we could invest lots of energy and hand-wringing in trying to change patterns of cultural participation, but I question what that ultimately accomplishes. It seems to me it’s really just moving around preferences in some kind of shell game for no real purpose other than to sustain specific institutions like those 25 companies in Clay’s post.

The real question is whether people feel like they have opportunities to lead an expressive life at a level that feels appropriate and in contexts that are meaningful to them. Just diversifying a theater audience isn’t necessarily going to do that, especially if in doing so you’re reducing opportunities for that theater’s former audience.

We have to remember that institutions can’t change the composition of their audiences single-handedly. They can modify their programming and marketing strategies all they want, but at the end of the day, it’s still up to individual people of color to decide whether that institution is worth their time or not. If there exists a theater that is of, by, and for a particular nonwhite community, why wouldn’t we focus on building up that theater’s capacity and reach instead? To make the value judgment that the current picture of theater attendance is “wrong” inadvertently calls into question, I fear, the validity of the existing aesthetic choices and preferences of people of color.

I should note that I haven’t yet touched upon money. That’s where the moral dimension of diversity in the arts comes into play. Is it right that a theater mostly serving a white audience can raise $30 million for a capital campaign while a theater with a substantially nonwhite audience struggles to get a $10,000 grant? Well, that’s another story. But we have to remember that there are plenty of mostly-white-serving arts organizations in the “have not” category as well. I think it’s easier to change patterns of cultural subsidy than it is to change patterns of cultural participation. (Not that it’s easy to change either!) It’s great to see a mainstream institution’s audience reflect its community, but in order to ensure real equity, our discussion of this issue must be person-centric (what are the opportunities for an expressive life available to this person?) rather than institution-centric (why aren’t there more butts of color in these seats?).

My two+ cents.

Apologies–apparently I forgot to close one of my blockquote tags in my post above!

I attend a fair amount of theater in Santa Cruz County. My wife and I have noted that we are often among the youngest in the audience, despite being over 50 ourselves. Theaters need to worry about age diversity even more than racial diversity—if they keep serving their current audiences, they’ll have no audience left alive in 20–30 years.

There are theater classes in Santa Cruz County for kids and a few for teens (my son is very active in some of them), but there is almost no theater aimed at audiences of teens. Even the high school plays get almost no teen audience. Price is not the primary obstacle here, as many of the theater events cost less than a movie ticket.

A major goal for all theater groups is going to have to be developing new audiences, whether by increasing the racial diversity of their audiences or (perhaps by the same mechanism) by increasing age diversity. The one theater group locally that seems to get a younger audience is Shakespeare Santa Cruz—and even it is heavily dominated by the white-hair audience.

I see a small amount of theater aimed at children (often brought to the schools) and a large amount aimed at retirees, but almost nothing aimed at teens and college students (other than student work at UCSC, which gets almost no visibility even on the UCSC campus). How are theater groups going to survive if they don’t produce anything attractive to people at a time when their tastes are getting set? People don’t magically become interested in theater when they retire—they just have more time for something that they’ve been interested in for a long time. If the interest is not developed early and so not there to be expressed, even the retiree crowd will disappear.

Hi Clayton, Great post! I loved learning how loving Cici has grown and expanded your understanding of the weight of whiteness, and helping her to love and appreciate all of herself.

I’m an old Theater Bay Area board alum circa 1980s, worked with Oakland Ensemble Theater, Lorraine Hansberry Theater, and the San Francisco Mime Troupe. Back in the day, Bay Area theater was diverse because there were companies such as Lorraine Hansberry, OET, Berkeley Black Rep, the Buriel Clay Theater, La Pena Cultural Center, the Asian American Theater Company, Cultural Odyssey, culturally specific companies who produced work regularly. Many of those companies are gone or operate with severely reduced budgets. New organizations have probably sprung up to take their place. There wasn’t much funding for these companies then however, and probably not much more now.

Unfortunately it seems like the more things change, the more they remain the same. (There was that infamous study produced by Jeff Jones around 1986 or so, published by the Examiner one fine morning, that roiled the theater and arts community. His report detailed who got money, how much, how often, percentage of funding provided to small, mid-size and large organizations in proportion to overall funding of the San Francisco Arts Commission. The report was a 7.0 on the Richter Scale.)

Surely in a nation facing unprecedented change due to changing demographics, our discussion about diversity in art and culture can evolve beyond that of 1983? It must. Because the changing demographics are real. And it will have an impact. Like it or not, this train has left the station. At the very least I suspect the demographic shift means that more support must be given to these diverse communities to support art in ways that makes sense for them. As they define it. These artists and their communities will lead the way and I hope that foundations and communities with resources will let them lead, and provide significant resources to them.

In other words, the challenge in front of us is not how we make existing mainstream organizations more diverse, rather how can we support artists and organizations who represent the future of our field? If we’d taken this approach thirty years ago, really invested in cultural and ethnically specific arts organizations, we’d be so much further along. But I digress. And I dare to dream. 🙂

Keep up the great work, Clay.

“What I have learned is that I didn’t know how monocultural my world was. I apologize to any readers of this who aren’t, you know, white and male, who find this particular revelation laughable–I get how obvious it may be, even as I hope you understand how surprising it was. ”

My entry point into finding out how monocultural my world was, was my African American husband. i totally get that you didn’t know how monocultural your world was. I certainly didn’t. It’s easy for a white person in the U.S. to never get it.

On another point,

“among the 25 companies [in the Bay Area] I am looking at there are no truly culturally-specific theatres”

I’ll bet those are white-specific theaters.

Louise, here’s my question for you: what makes a “white-specific theatre?” I once interviewed a playwright who complained that in the Bay Area, most theatres probably would consider themselves “white-specific” if they had their druthers, but that as it was they claimed to serve everyone while only caring about a small slice of the pie. Without putting judgment on whether a “white-specific” theatre is more or less valid than an “African-American theatre,” if those “white-specific” theatres don’t have the bravery to speak the truth of their work in their missions, my opinion is they should be held to what their missions actually say, rather than what happens now, which is we give them a pass because we think that Shakespeare and Beckett and new work is “white-specific.” It seems to me a problem in our field if, unless you call yourself out as a company that serves, for example, Middle Eastern audiences, you are given a pass on being a white theatre and are expected to not try to be something more.

Now, one thing that is interesting to me and that I’m having trouble sorting through is this question of whether certain work (or artforms) are inherently white-facing (or old-facing, or rich-facing). There will always be exceptions of course, but should we just assume that the majority of theatre as a form is a white medium, give up this ghost of speaking for and to everyone, and allow the form to slowly wither as the white population shrinks, wealth is resdistributed and the work stagnates? This, as depressing as it seems to me, also seems sort of a legit (if troubling) option. But I don’t know…

“There will always be exceptions of course, but should we just assume that the majority of theatre as a form is a white medium, give up this ghost of speaking for and to everyone, and allow the form to slowly wither as the white population shrinks, wealth is resdistributed and the work stagnates? This, as depressing as it seems to me, also seems sort of a legit (if troubling) option. But I don’t know…”

I think for this to happens there’s going to have to be a critical mass of an ethnic population. Until that mass is reached, the fixed costs for most (larger) arts organizations will make it prohibitive to have anything along the lines of a professional level arts organization designed specifically for an ethnic population. There’s a reason that Detroit/Dearborn and NYC have large Arabic Orchestras and the Bay Area has several larger Traditional Chinese Orchestras while other cities with more modest populations of Arab-Americans and Chinese-Americans only have smaller ensembles or none, as the case may be. Outside of the University setting (mainly schools with big ethnomusicology programs) you won’t find large ethnic ensembles except in regions with big enough ethnic population to sustain it.

Theatre might work a little different as the narrative content might help offset idiosyncratic aesthetic tastes and especially since most non-Western theatre is “mixed-genre” and not so text-based. But I know that up till the 1950s, there were at least 6 Chinese Opera troupes operating in a regular basis in NYC (even during the Asian-Exclusion Act era) and the Bay Area used to be the hub (during the mid to late 1800s/early 1900s) of a lot of Chinese Opera productions, or served as the starting point for tours of Chinese based troupes when they would tour the States–this was one of the reasons that Mei Lanfang was able to rise in popularity here in the states.

I note that the theatres I’ve been to with the youngest audience demographic have been ethnic theatres, specifically Bindlestiff (Filipino American) and Asian American Theatre Company, with average audience ages of about 30. Next up are indy theatres, going from younger to older perhaps Crowded Fire, Impact and Cutting Ball. The thing that all five of these theatres have in common is that they at least sometimes, if not all the time, do risky work.

I note Marin Theatre Company has two African-American-themed plays in its season this year.

My family diversified through interracial marriage after I left home, so I have a vague awareness of it within the family. Living in San Francisco did change my awareness so much so that when I visit white places I feel like I’m on another planet. But I still have to remind myself about diversity anyway.

So what can this white male do? As a playwright, I’m trying to write more roles specifically for actors of various colors. My current play-in-progress, My Visit to America, calls for three biracial actors. Of course, it has to be good enough and of interest to a theatre to get on stage, but it’s something that is within my power to do. A challenge, though, has been to get feedback from non-whites; I only recently got some cultural review from indigenous Americans, resulting in some rewriting. My last reading was at least cast racially accurate and the actors gave me positive feedback, but you have to wonder, this being the yay bay, whether they felt okay giving me a frank opinion. I also fear that other whites will not understand this play, although not enough to not write it.

But we have to try.