I want everyone in the world to cover the arts. I want people who don’t love the arts to write about the arts, I want people who do love the arts to write about the arts. I want the New York Times critic to write about the arts, I want the blogger who started her blog in the morning and wants to review that evening to write about the arts. Art art art, all around us, can’t swing a dead cat without hitting the arts. That is what I want, so let’s be clear about that before we get going.

I’m working on a new Michael Gordon release called Timber, which will be released physically in a couple weeks. Timber was written for 6 percussionists playing 2x4s (“simantras”), so “physically” actually means a one-pound, hinged box made of medium-density fibreboard. Normally, I would mail physical CDs to a “classical priority” list of about 80 journalists, but for the sake of the pressing and mailing costs, I whittled (WOOD PUN) the list down to 50. Twice, already, I’ve gotten asked by folks at radio stations to which I’ve sent 2+ copies for an additional copy. I’m happy they or anyone, really, wants to hear the crazy/wonderful evening-length piece my composer wrote for 2x4s, but you can share; these copies are for work, not for future family Christmas presents.

My friends who work at record labels have the best collection of ridiculous journalists requests. “Have I fallen off your mailing list?” one writer inquired after retiring from the publication that had previously employed him. When a colleague asked a person at a less-trafficked blog if he would consider a download copy of an album for review–any type of file he needed with high-resolution cover art and the PDF of the full booklet–the blogger responded, “We still cover only the physical product at [blank], not downloads. So please be sure we get it. I don’t even open the download e-mails, so have no idea what is there.” You, yourself, don’t have a print edition, yet you need something physical? Fascinating.

Here’s another gem: “Incidentally, I just received a screener for [blank] doing the [blank]. I usually don’t review anything but finished product (because I don’t get paid for this; I do it as a hobby, and there is no incentive for reviewing something I can’t put into my collection with proper art work and booklet insert).”

And this may be my all-time favorite: “I can only hope the gash over the bar code will not be as severe as it’s been for some other items.”

A directory writer once told me that he said he would never listen to or review a digital release because he “just needs to hold something.” He then proceeded to talk about how his publication was going to an online-only directory.

This one gets points for honesty, at least: “I won’t pretend I have an assignment to review the new [blank]; I don’t! However, if you have a promo copy you don’t know what to do with, I’d love to hear it and not via download.”

The artists themselves get a certain number of physical discs and then have to pay for them, per their contracts. Management companies have to purchase CDs at reduced cost for booking purposes. Why, then, should writers get to stock their personal collections with no intention of reviewing a recording, or without the responsibility of proving that their review may actually sell a copy or two? As Anne Midgette pointed out in the Washington Post in January of 2010,

The dirty secret of the Billboard classical charts is that album sales figures are so low, the charts are almost meaningless. Sales of 200 or 300 units are enough to land an album in the top 10. Hahn’s No. 1 recording, after the sales spike resulting from her appearance on Conan, bolstered by blogs and press, sold 1,000 copies.

…SoundScan, the company that provides sales data to Billboard, says it cannot officially release exact sales figures to journalists. Instead, all numbers are rounded to the nearest 1,000, so sales of 501 copies are reported as 1,000, and anything less than 500 is “under 1,000.” On last week’s traditional classical chart, only the top two recordings managed to sell “1,000” copies. Every other recording (including, in its second week, Hahn’s) sold “under 1,000.” The official total sales of the top 25 titles amounted to 5,000 copies, an average of 200 units a recording (sorry, “under 1,000”). And yes, that includes downloads.

My full classical press list has 644 names on it. If I mailed a physical copy to every person on that list, the free goods could equal the first week’s sales of the top classical CD on the chart.

Hearing the music is really the most important thing, and in 2011, there are many ways to accomplish that on all sides. We used the excellent site Bandcamp for digital downloads of Timber, for example. As a friend at a classical label wrote,

This first thing to know is that record companies want journalists and radio stations to hear the music, and hopefully spread the word. The second thing to know is that this is a business: everything costs money and when it comes to sending out promotional CDs the costs are not insignificant. It is not only the cost to manufacture the CD but also packing material and shipping, not to mention all the initial costs of the recording itself (artists, engineers, producers, studio time, mixing, mastering, the list goes on). Setting aside initial costs, your 1 promo CD can easily cost between $5 and $10 (feel free to consult the UPS website for rates) – it is not free.

As with all business relationships (this is a business not a hobby) there are reasonable expectations of reciprocity. Asking you for circulation, web traffic or listener numbers is not an insult – it’s my job. Lots of people have opinions and express them, especially online, but everyone is not heard equally. In the spirit of wanting to make sure that our music is heard companies do offer financially more responsible options for hearing music – if those options are not acceptable because you need the finished goods for your personal library, we might need to have a little discussion. The music and the complete liner notes should be sufficient in almost all cases.

Let’s all be honest. If I Google search and can find no mention of my CDs in the last 12 months from you, I’m not sure why I should keep sending them: receiving free CDs is not part of your job description. While it would be ill-advised to not send out promo copies for review, it is equally ill-advised to send out CDs with no accountability.

Another bit of honesty has to do with your outlet – it is natural that larger publications and radio stations have more reach and impact. To re-iterate, we want you to hear the music, but if I am to spend thousands of dollars every year sending you promo goods (indeed, thousands), I need to know that in some way there is a return on that investment. In 2011 everything can be tracked – not only sales, but how many links point to you, how many people have read your review, how many people are listening to your station. We are all here for the music, but we also have businesses to run – let’s not lose sight of either part of the equation.

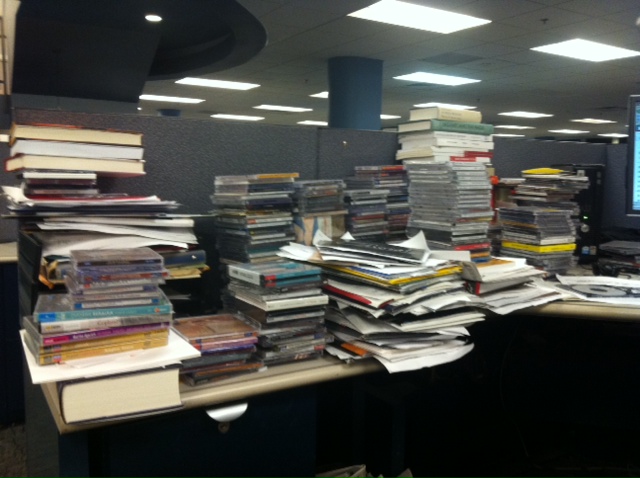

Meanwhile, back at their ranches, journalists are overwhelmed by CDs. Here’s a photo of the desk of the of a working music critic:

This writer says writes via e mail:

It’s a conundrum. Of course I need to know what’s coming out. And of course I want to continue getting CDs from small labels, and little-known composers, and local groups, and performers who have saved and scrimped and gone on Kickstarter to make their own recordings after years of honing their interpretations, as well as the major labels. But Naxos alone distributes a couple of hundred releases a month. There’s just more than I can possibly listen to. This picture is only a small fraction of it: I have equally large stacks of CDs around the CD player at home.

Here’s that same critic’s home:

(I love the brave little iPod centered on the shelf there, looking terrified by all the jewel cases.)

Writers get messages from labels and publicists saying that they only have a limited number of review copies, and that critics should let them know what they’re interested in, but then they often send it all anyway. It’s tough to get coverage, and we the publicists are all scared writers will miss our clients’ projects. Oftentimes, actually, writers will get CDs from the artist’s publicist, the artist’s label, and, if there’s a conductor or multiple artists on the record, those artists’ people.

And what of downloads? Sure, the music critic quoted above said, but due to the volume of physical CDs they get, they favor what’s on their desk and sometimes forget to download.

Concert tickets, like CDs, cost money: those are premium seats that cannot be sold. A New York City venue told me earlier this year that no journalist who wasn’t reviewing could get a comp ticket for one of my artist’s recitals there, and that the New York Times reviewer couldn’t have a +1. I explained that I had bigger profiles for my artist in the works, but was told that was my problem, and that I could use the artist comps or buy the tickets for those writers. That seems shortsighted as a venue policy, since it wouldn’t have hurt to have their venue included in these bigger profiles, but to some extent, it’s understandable; they want to sell as many tickets as possible. Again, a hundred dollars or so in tickets vs. being spotlighted in a major glossy magazine? Seems silly, but it’s their call. Opening night of The Metropolitan Opera’s Die Walküre this season, one journalist, who was presumably not assigned to review, Tweeted his frustration that the Met took away his ticket. A writer recently complained to me that The Met was only giving him “one ticket!” to the opening night of The Met’s season this fall.

I asked a friend who works in a presenter press department about his feelings on the subject. He wrote,

You are not prohibited from buying a ticket. Our performances are open to the public and we love to sell tickets. Do not confuse “I want to see this and I’m a journalist” with “I need to be admitted to this for free so that I can cover it as a journalist.” If you get offended when I ask in what capacity you will be covering the event, something is wrong.

Regarding the inevitable request for 2 tickets and your inevitable complaining when we can only give you 1: you are attending the performance to do your job. I do not get to bring a friend with me to work. No one in almost any profession gets to bring a friend with them to work. It is nice that sometimes in our profession you get this opportunity, but why are you so entitled about something that should have no impact on your ability to do your job? Your social life is not my responsibility.

The fact that you are a journalist who has covered my clients in the past, or is “important” in another way (an editor or writer for a major publication who covers our art form infrequently, say) does not mean you have an open invitation to see whatever you want for free. I am taking expensive tickets off sale for you. Please try to be ethical and—perhaps—consider buying a ticket to something you just want to see. I’ll be happy to help you.

It all begs the question: is giving out free CDs and free tickets even ethical? Is it not a bribery-adjacent? Restaurants don’t comp meals for food critics. In fact, Ruth Reichl wrote a whole book on reviewing restaurants in various disguises when she was at The New York Times.

Let’s get back to the subject at hand. So you–you, happy few–work at a newspaper or a magazine full time and you don’t have much of a problem getting tickets and CDs, even if you’re not exactly reviewing every concert you go to or CD you review. What if you’re a freelancer, and need material to pitch various editors to get assignments? Not everyone’s a staff music critic–not everyone wants to be a staff music critic–and not all coverage occurs in a neat A to B line.

I asked a freelancer’s opinion:

As a journalist, some of my best stories have come from places I would have never expected. Often the things you go to when you’re not on a deadline, or composing a specific piece for, speak to you in a stronger way, because you more open to it. In a perfect world, the barriers between someone who is “on duty” and “off duty” would be clear, but we don’t live that world. PR depts could say no to any free tickets. This would be insane, of course: the publicity created by a few articles/reviews is worth vastly more than the ticket prices. My thinking is, if you’re going to give some people free tickets, you have to give free tickets all–within the allotment you have, of course. But if you’re thinking long term, and have a client of substance, making a few phone calls to try to squeeze in some extra journalists—who could be easily brushed aside—could make a big difference down the road.

You could think of journalists as donors/patrons. Treat them well, and try to expose them to as much of your client/organization as you can. If you do everything possible to cater to their needs (which often can be idiosyncratic and less than clear) you will reap the rewards of what they can offer. Sometimes they have to be said no to. This is part of life. But make an effort, because saying no once in an impolitic manner may mean they will never return. Yes, they may not always deliver, but PR people complaining about comp-ed journalists should ask the development office how much they spend to land one premium donor?

I’ve had PR people give me a hard time about credentials and assignments, and then pitch me things that make it clear they have no clue about the beat I cover and what type of pieces I write. If you’re a PR person lucky enough to have enough demand that you honestly have more journalist requests than room for them, then you’re job is to know the best outlets for your client. You should know what writers are real and which are not—its not that hard to determine real journalists from fake ones, if you’re actively reading what’s out there. Press relations, “relating to the press,” as it were, is a two-way conversation.

There is a major financial crisis in the performing arts right now. There is a major financial crisis in journalism right now. There is a major financial crisis in finance itself right now, but none of us have any money so that’s not really our problem. The best thing to do, as with most aspects of this little life of ours, is to develop good relationships, do good work, and let your work speak for itself. There are some journalists to whom I would send my only copy of a CD, journalists for whom I would fight press departments for a comp ticket, and journalists at less-trafficked outlets with whom I would happily secure an interview with any of my clients. They’ve earned my trust, hopefully I’ve earned theirs, and onward we go, spreading the gospel of classical music from town to town.

Perhaps the more important question here, though, is if publicists, presenters and labels think press coverage even sells tickets and CDs. If we do look at this as a business, and we should more than we do, how do the finances work out? How much money do labels spend on press copies and how much ticket revenue do presenters lose in comp tickets, and can they track if the resulting coverage has financially benefited the company?

I suggest that those who are insistent upon receiving a physical copy, unless they are one of the larger print publications, may not warrant one. In the past, groups I was involved with,would only submit to print publications actual physical CDs. Why, because they had some “skin in the game”. Ultimately what seems to be forgotten by electronic publications, is that when the electricity goes down (e.g. websites disappear), so does the review. How is this helpful to the artist and what does this say about the investment. Not so with physical printed magazines. Even should a physical publication cease, the reviews are floating around somewhere on a printed copy. That’s a better artist investment for long term.

The state of music today is digital, there is no doubt about that given the fact that downloads are the most significant means of distribution at this time. A given number of physical CDs will outlast, in shelf life, those digital downloads the day that their digital business cease operation, or hard drive crashes; no more copies to be had. We can’t ignore the current business model, but we don’t have to go broke trying to satisfy those that can’t see their relevance to the long term goals of artist promotion.

Here’s another perspective: As a free-lance broadcast journalist my goal is to provide media support for the arts. If the arts orgs appreciate that, they will help me do my job. I attend hundreds of concerts for work. Do you think as a journalist that I can afford to pay for those tickets? Even if I’m not broadcasting a specific concert, I’m still getting to know the music and the musicians so I can support them over the long term. It’s relationship-building. Those CDs I’ve accumulated over the years are a nuisance to store and catalogue, but they are the tools of my trade and I need them at my fingertips.

In my series of national broadcasts from American music festivals, I pay for travel and housing and recording gear, for admin and distribution, for promotion and time spent interviewing and audio editing. Last summer I paid my own airfare and $1500 our of pocket to create a national broadcast for one festival in particular, and they in turn gave me a single ticket, limited the concerts I could attend, told me I wasn’t invited to events where I could interact with the artists to capture the flavor of the festival, and prevented any contact with the recording engineer. I delivered their music to 250,000 listeners, and they in turn burned their bridges.

With the decline in arts journalism, the artists need us now more than ever. There are a lot of out-of-work journalists out here trying to get freebies so they can keep networking, but there are also a lot of us working on a shoestring to support the music. So, arts organizations, I hope you’ll keep those good relationships so we’re here for you when you need us.

That brave little iPod is just as dated as those jewel cases.

People are selfish, and it can be infuriating. Honestly, I don’t understand why anyone would want to have all of those cds cluttering their homes. I’m at the point where I don’t have space to store all of unsolicited discs I receive (even for a little weekly radio program), but I feel very uncomfortable unloading CDs I got for free to record shops.

Doug, I’m glad to see you say that you’re uncomfortable selling CDs you got for free to used record shops. Not nearly enough people are that scrupulous.

If there are old review CDs that you just can’t keep because you’re out of space, I recommend donating them to a public library. These days public libraries are always strapped for funds, and you can be pretty sure that the CDs will actually get listened to.

I work in a library and the donation idea is good, but ask the library before you bring them in. They may not want all of them.

Have you considered giving those CDs away as prizes to your readers?

Some of the CDs are not very good, so I’d hate to give those away, but I am definitely going to reach out to my library ASAP. Thanks for the idea!

I’m not sure I agree with the journalist quoted in the story (and Marty, commenting above) that all press coverage is a net positive for an artist.

What if you’re a publicist whose client is at the absolute top of their field, someone whose performances regularly sell out when they are announced? You could take a lot of tickets off sale to accommodate reviewers who may or may not write nice things about the artist (and odds are, you’ll probably get at least one negative review, no matter who the artist is), which leaves you a little worse off, financially and reputation-wise, than when you started; or you could accommodate fewer reviewers, thereby selling more tickets while minimizing the possibility of a bad review.

Just something to think about. I do think it’s important for the arts to be covered everywhere, and you could make an argument that more visibility for even a famous classical musician is good for the industry in general, but I can definitely see why for some artists, it might not be true that any publicity is good publicity.

Amanda:

This was a flash of utter brilliance! Tell Michael Gordon he should retain you for life…

BTW: I’m largely with your freelancer here. You do have to trust your instincts. And, if a writer is credible, sometimes you have to bend over and send them the free copy, or comp them a ticket. When I was working at a major record label, I spent a tremendous amount of time reading different writers, bloggers, reviewers — most of whom fell under that gray area of freelancer. Often, I would comp them, even though I knew they wouldn’t be reviewing anything immediately. I reaped a lot of rewards that way over the years. It’s part of developing relationships with writers. Of course, I also had to turn away what I called “product hogs”, those wacky old men (and they largely were all old men), who filled out their request sheets by checking every release available in a given month. This practice was finally stopped when the company put a limit on all writer requests. That did get them to think a bit more about what they were requesting, but they still got a nice package of recordings, most of which they didn’t review. And, I still got panicked letters and emails from writers who “just couldn’t decide”. They might review X, but Z looked so tasty — and how could they make such a dreadful choice?

As for venues, I have really come to dislike their pr departments on the whole. I do understand the need to be careful with comps — and agree that giving someone 2 is excessive — but I’ve had one too many credible writer colleagues denied tickets by the “bigger ones” in New York mostly out of laziness or shortsightedness. Recently, one friend — who writes for ON, among several other publications, had an assignment from a foreign music magazine to review Selma Jezkova, and the folks at the Lincoln Center Festival IGNORED him. He has no trouble with the Met, particularly if he is willing to forfeit “opening night performances”, but the LC Festival has ignored him for two years running now. And, this is a guy with assignments…not just a writer who wants to attend the festival.

Last word on CD comps: As a private citizen/record collector: nothing will EVER replace physical product. There is something about having it in your hand that is impossible to replace. I’ve never been satisfied with something I’ve only purchased as a download. Hard drives crash, iPods die, and there is just something wonderful about a beautifully-packaged recording, with great program notes, or other “extras”. God knows that Michael Gordon recording falls into a “must-own the physical product” category. Yeah, I know — order it on Amazon. I just might, once I get another client, that is….

Love your writing, Amanda. Tough, real, and comprehensive.

What about a “middle-ground” compromise: record labels send digital press releases and download links, but with an open-door invitation to request a physical copy. Reviewers would be under no obligation to actually review the album in question, but would be indicating two things: “I think I could have something to say about this” and, just as importantly, “I have room in my schedule to write something about this album”, or “I want to have this in rotation for a potential future review or article down the road”. This would cut down on our record label costs, considerably, without substantially limiting the access that reviewers have to the best version (if that’s what they consider a CD) of our product.

Whilst I am a PR for mainly rock and metal bands, the conundrum remains the same as my classical brethren here. Some online sites will only accept digital submissions, some publications will only accept physical…my preference is to send out promo CDs in plastic sleeves – this cuts down significantly on mailing costs – and then send a finished article of the journalist requests it, as long as they have done something around the release, or might potentially do something.

I, like ‘Ananymous’, prefer to have the physical release – something to look at, touch, read, that won’t vanish the minute my hard drive goes (yes, we should ALL back-up regularly….but who does?) – and, maybe due to the genre of music I work in, many of my press and radio contacts prefer this as well.

The other ‘bonus’ of sending out physical is that journalists DO have something there in front of them – many a time I’ve had a last-minute review run as something else has been dropped/moved back, and that promo CD was sitting in front of them…

Fascinating article – and my first visit to your blog. Cheers.

I love receiving physical copies of CDs – I still prefer a good old vinyl album, but it’s been many years since I received a review copy of one of those. However, I recognise that the costs are escalating and as a reviewer I have no wish to make things more difficult for the artists or the labels. So if I’m offered a download, as long as it comes with cover art, liner notes, etc, I’m happy. The jazz world [which is the one I know best] seems to be at a bit of a tipping point as regards CDs v. downloads. Most of what I receive is physical product but a few companies are moving to downloads. The website I write for the most has no policy about physical v. digital product.

I must admit, I often review the entire package, not just the music on the recording. I figure if someone might actually be willing to pay for a CD then they deserve to get a good quality physical package – after all, the fan is probably paying more than they would if they were just buying downloads – so if the cover art is especially good/poor, or the liner notes/booklet is particularly informative, funny, or just plain weird then I will comment.

As for live reviews, I never think about scoring a freebie if I am not actually reviewing an event. If I’m offered a +1 then I often accept, if not, then I’m Billy No Mates for the evening and that’s fine.