Photo Chapman’s Homer, Christchurch by Duncan C, published on Flickr, Creative Commons License.***

A couple weeks back I had the privilege to give a talk in Christchurch, NZ at an event called The Big Conversation—hosted by Creative New Zealand, the major arts funding body for the country. The talk, Transformation or Bust: When Hustling Ticket Sales and Contributions is Just Not Cutting It Anymore (click on the link and it will take you to a transcript) was intended to address the general conference theme, Embracing Arts / Embracing Audiences. It was assembled on top of four cornerstone ideas:

- Michael Sandel’s argument that we have shifted from having a market economy to becoming a market society in which, as he puts it, market relations and market incentives and market values come to dominate all aspects of life.

- The notion that, paradoxically, the arts are facing a crisis of legitimacy (says John Holden) at the very moment when we have so much to potentially contribute as a remedy to the erosion of social cohesion that is resulting from global migration, economic globalization, a culture of autonomy, and the Internet (see the David Brooks op-ed, How Covenants Make Us).

- The four futures for the social sectors predicted by NYU professor Paul Light in the wake of the 2008 economic crisis: (1) the unlikely scenario that nonprofits would be rescued by significant increases in contributions; (2) the more probable scenario that all nonprofits would suffer; (3) the most likely scenario that the largest, most visible, and best connected nonprofits would thrive while others would fold; and (4) the hopeful scenario that the sector would undergo positive transformation that would leave it stronger and more impactful, likely only if pursued deliberately and collectively by nonprofits and their stakeholders.

- And a concept I encountered on Doug Borwick’s excellent blog:Â transformative engagement, by which Doug means engagement with the community that changes the way an organization thinks and what it does.

Building on these, I argue that in the US arts and culture sector we have for too long ignored or denied the costs of so-called progress in the arts–meaning, for instance, the costs of professionalization, growth, and the adoption of orthodox marketing practices including so-called customer relationship management and I suggest five ways that arts organizations may need to adapt their philosophies and practices in relationship to their communities if their goal is deeper, more meaningful engagement.

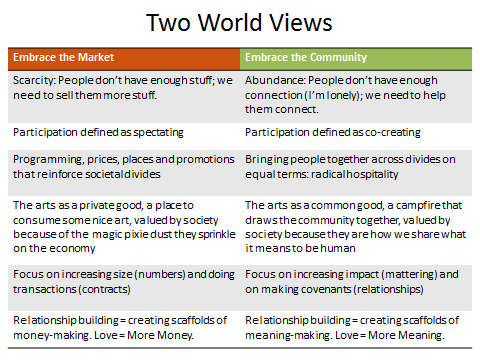

Ultimately, I pull the various threads of the talk together in a framework that seeks to conceptualize the difference between embracing the community and embracing the market. In setting this up, I build on Internet guru Seth Godin’s notion of, essentially, competing worldviews that inform the way companies approach marketing. In an interview with Krista Tippett on her NPR show, On Being, Godin remarks:

There’s one view of the world called the Wal-Mart view that says that what all people want is as much stuff as possible for as cheap a price as possible. … And that’s a world based on scarcity. I don’t have enough stuff. How do I get more stuff?… There’s a different view, which is the view based on abundance. [And] in an abundance economy the things we don’t have enough of are connection …and time.

Here’s the PPT slide of the framework I created that synthesizes the various ideas in my New Zealand talk:

In many ways, this talk explores an idea that I first began to ponder when I wrote a blog post for the Irvine Foundation in response to its question: Is there an issue in the arts field more urgent than engagement? If so, what is it?

In my post, I answered the question in the affirmative and then offered the following as a more urgent issue:

While lack of meaningful engagement in the arts is indeed troubling, I would offer that a larger problem is that the nonprofit, professional arts have become, by-and-large, as commodified, homogeneous, transactional, and subject to market forces as every other aspect of American society. From where I sit, the most important issue in the arts field these days may be that the different value system that art represents no longer seems to be widely recognized or upheld — by society-at-large, or even within the arts field itself.

For the New Zealand talk I tried to explore the ramifications of the loss of this “different value system” (Jeanette Winterson) and how it relates to the issue of engagement.

Gap Filler: On Sustaining the Social Cohesion that Emerges out of Disasters

Because the conference took place in Christchurch (where two devastating earthquakes struck in 2010 and 2011) I reflected at the top of the talk on the solidarity and social cohesion that often arise in response to natural disasters. In his new book, Tribe,  Sebastian Junger introduces the seminal research of a man named Charles Fritz to explain why this is. Fritz asserts “that disasters thrust people into a more ancient, organic way of relating.” … “As people come together to face a threat,” Fritz argues, “class differences are temporarily erased, income disparities become irrelevant, race is overlooked, and individuals are assessed simply by what they are willing to do for the group” (Junger 2016, 53-54).

Yet, as Junger reports, all too often, these effects are temporary. One of the best parts of the conference in New Zealand was being introduced to some amazing organizations and projects here—including Gap Filler, an intiative that began with a few people asking how they could sustain the sense of fellowship, volunteerism, and community that arose out of the first earthquake. One of the co-founders of Gap Filler, Dr. Ryan Reynolds, gave a truly inspiring presentation at the conference. It struck me listening to his story that Gap Filler could be the poster child for Creative Placemaking.

Gap Filler’s first ten-day project was launched in November 2010. It began because Reynolds and others wanted somehow to fill the gaps in the physical and metaphysical landscape of Christchurch left by the loss of hundreds of buildings, including dozens of bars, clubs, and restaurants. They had the idea to gather a group of volunteers together to transform the empty lot where a popular restaurant, South of the Border, once stood into a temporary space for citizens to once again come together and eat, drink and socialize. Over the course of ten days—and driven largely by citizens who showed up on their own initiative to contribute to and enjoy the temporary space—the site came to host a temporary garden café, live music, poetry readings, an outdoor cinema, and more. The success of this first project led to further initiatives including art installations, concerts, workshop spaces and eventually semi-permanent structures. You can read more about Gap Filler’s projects here. (And here is an article, written in 2013, about the revitalizing influence of the earthquake on the Christchurch arts scene.)

Gap Filler was only one of several remarkable organizations/projects I heard about at The Big Conversation.

In any event, if you read the talk, I hope you find it worthwhile and will share any responses to it on Jumper.

And speaking of things worth reading …

Nina Simon has a new book out! Those who have read Jumper for a while, or have heard me speak at conferences, know that the topic of matteringness or relevance is one I have been circling and diving into with some regularity for the past decade—and I am by no means alone in this. One of the greatest minds on this topic is Nina Simon at the Santa Cruz Museum of Art & History and she has a new book out—The Art of Relevance. I won’t be united with my copy until I’m back in the US next month, at which point I look forward to reading it and writing about it on Jumper. In the meantime, I strongly encourage anyone interested in the topics of relevance, engagement, or participation in the arts to buy it and read it, as well.

***This photo is of the stunning sculpture by Michael Parekowhai, On First Looking into Chapman’s Homer,  and it was taken at one of the many sites where the work was situated in Christchurch following its presentation at the 54th Venice Biennale. It is currently housed at the Christchurch Art Gallery and is considered to be a symbol of the resilience of the people of Christchurch following the earthquakes.