A couple weeks back the Irvine Foundation launched an online Q&A series, Are We Doing Enough?—aimed at “exploring tough questions about engagement practices and programming.” I was delighted and honored to be one of a small group of “outsiders” asked to provide some reflections in response to one of the Qs. The first two issues of the series (Part 1 and Part 2) featured a group of Irvine’s current grantees, as well as Irvine arts program director Josephine Ramirez, addressing such questions as: Should artists be responsible for creating art for the purpose of engaging communities? What purpose do “engagement events” serve if people don’t start showing up at the museum? and Are culturally and racially-specific organizations negatively affected when mainstream arts organizations offer diverse programming?

Clay Lord, Vu Lee, Karen Mack, Teresa Eyring and I were asked to address the question: Is there an issue in the arts field that is more urgent than engagement? You can read how we responded here. I want to use this post to elaborate on my response, the conclusion of which was this:

While lack of meaningful engagement in the arts is indeed troubling, I would offer that a larger problem is that the nonprofit, professional arts have become, by-and-large, as commodified, homogeneous, transactional, and subject to market forces as every other aspect of American society. From where I sit, the most important issue in the arts field these days may be that the different value system that art represents no longer seems to be widely recognized or upheld — by society-at-large, or even within the arts field itself.

As I’ve mentioned from time-to-time on Jumper, the topic of my dissertation is the evolving relationship between the commercial and nonprofit theater in America—how it has changed over time, why, and with what consequence. Some of the deeper questions motivating my research have been:

- What is nonprofit professional theater for?

- Are there clear differences between the way the theater that exists for the primary goal of making money relates to its employees, customers and market and the way the theater that exists to improve society through art relates to its front-line missionaries (i.e., staff and volunteers), beneficiaries (i.e., artists and audiences) and the community-at-large?

- If not, or if these have been eroding over time, is this cause for concern? Can and should we stem the tide? And if so, how?

In 2011 I helped to plan and document a meeting of nonprofit and commercial theater producers, who were gathered to discuss partnerships between them. Candidly, the room seemed rather stumped for an answer to a version of that first question. A few ideas were tossed out but nothing stuck–in large part because, as more than a few participants observed, nonprofits and commercial producers “are more and more the same in practice.” As I wrote in the report (available here in paperback or free e-file) anaylyzing the meeting:

Many noted that it is no longer evident what value nonrofits bring to the table, distinct from commercial producers. Some suggested that the interests of nonprofit and commercial producers are now aligned to the point where the shape of [their] intersection is less like a crossroads and more like two lanes merging on a highway.

And why is that?

Well, lots of reasons. But part of the issue seems to be that the 20th century witnessed not just the professionalization of the community arts but their corporatization. Once labors of love by amateurs, arts groups across the US incorporated as not-for-profit corporations but then put corporate leaders on their boards, hired staff with more corporate management skills, adopted corporate marketing techniques, and looked to major corporations like hospitals and universities for models on how to raise money and advance their institutions. Savvier arts nonprofits also opened for-profit subsdiaries, formed partnerships with commercial enterprises, or became real estate investors or developers … basically, they pursued any and all means of exploiting their assets. And, ironically but not surprisingly, much of this sort of activity was actively encouraged by private philanthropists and government agencies.

What’s been the cost?

In her book Three Guineas, Virginia Woolf writes:

If people are highly successful in their professions they lose their senses. Sight goes. They have no time to look at pictures. Sound goes. They have no time to listen to music. Speech goes. They have no time for conversation. They lose their sense of proportion—the relations between one thing and another. Humanity goes.

I don’t know about you, but I find this statement to be disturbingly resonant.

Here we are in the 21st century and it strikes me that the nonprofit arts have become increasingly dehumanized–which is ironic since arguably one of the primary benefits of the arts is that they stimulate the senses, awaken us to beauty, fill us with awe, connect us to others, and inspire us to be better humans. But as David Brooks seemed to be arguing in his January 15 column When Beauty Strikes Back (for which he took quite a bit of flack), the arts have forgotten or rejected this role and society is poorer for it. He writes:

These days we all like beautiful things. Everybody approves of art. But the culture does not attach as much emotional, intellectual or spiritual weight to beauty. We live, as Leon Wieseltier wrote in an essay for The Times Book Review, in a post-humanist moment. That which can be measured with data is valorized. Economists are experts on happiness. The world is understood primarily as the product of impersonal forces; the nonmaterial dimension of life explained by the material ones. …

The shift to post-humanism has left the world beauty-poor and meaning-deprived. It’s not so much that we need more artists and bigger audiences, though that would be nice. Â It’s that we accidentally abandoned a worldview that showed how art can be used to cultivate the fullest inner life.

Perhaps the arts are losing a battle over the minds and souls of society in large part because we don’t seem to recognize that we have been fighting for the wrong side–don’t recognize it because, as Woolf says, we have lost our senses. We have been swept up in econometrics and CRM theory and funder logic models and we have lost our ability to see what is in front of us and to be distrubed. It now seems normal to us that some heads of nonprofit resident theater companies, for instance, earn hundreds of thousands of dollars a year while even great actors in America are leaving the industry because they just can’t bear living on the cliff’s edge of poverty year-upon-year–a circumstance that should be appalling to anyone running a nonprofit theater, if one recalls that a fundamental purpose for nonprofit professional resident theaters when they were envisioned in the mid-twentieth century was to provide a stable, living wage to actors.

That’s losing the relations between one thing and another … that’s losing your humanity.

***

Speaking of poverty, if you didn’t see the press a few days back, the Irvine Foundation made the major announcement that it will “begin work on a new set of grantmaking goals focused on expanding economic and political opportunity for families and young adults who are working but struggling with poverty.”

President Don Howard wrote in a blog post:

These are mutually reinforcing goals. If all Californians are to have real economic opportunity, their voices must be heard and their interests counted. Responsive and effective government shapes the policies that allow people the chance to earn a wage that can enable a family to live in a safe, healthy community, send their kids to school, and realize their potential. Conversely, if all Californians are to be heard, they cannot teeter on the precipice of poverty, lacking the time and the conviction to meaningfully participate.

This is Irvine’s evolving focus, and as the words suggest, the changes will occur over time. As many of you know, we are deeply engaged in important and successful grantmaking. We remain firmly committed to our current grants and initiatives, many of which are in the middle of multiyear plans driving toward specific impacts. We will see all of these current grants and initiatives through to their planned conclusions. And some will evolve to be part of our future work.

As I read the last paragraph I thought … Hmmm, I wonder how the arts program will fare in this evolution? Will it be one of the programs phased out?

What’s the case for the role of professional arts groups in expanding political or economic opportunity for families living in poverty? Venezuela created El Sistema. What have we created of late that comes close to having that scale of impact on the lives of the most impoverished? Has there been anything since the Works Progress Administration (a New Deal initiative under FDR), which gave us the remarkable Federal Theatre Project and related projects in other disciplines? The Federal Theatre Project, if you don’t know it, was a work-relief program that made significant funds available to cities and towns across the US to hire out-of-work artists. It resulted in a flowering of hundreds of new ad hoc companies that collectively brought vital, relevant theater—including The Living Newspaper, a form of theater aimed at presenting reflections on current social events to popular audiences—and other forms of art to millions of people who had never had such experiences. It was a short-term relief program intended to do two things: alleviate artist unemployment and awaken and inspire America as it struggled out of a Great Depression.

And it exemplified the extraordinary role art can play—when it is for the advancement of the many, rather than the few—in helping a nation that is struggling to find a way forward.

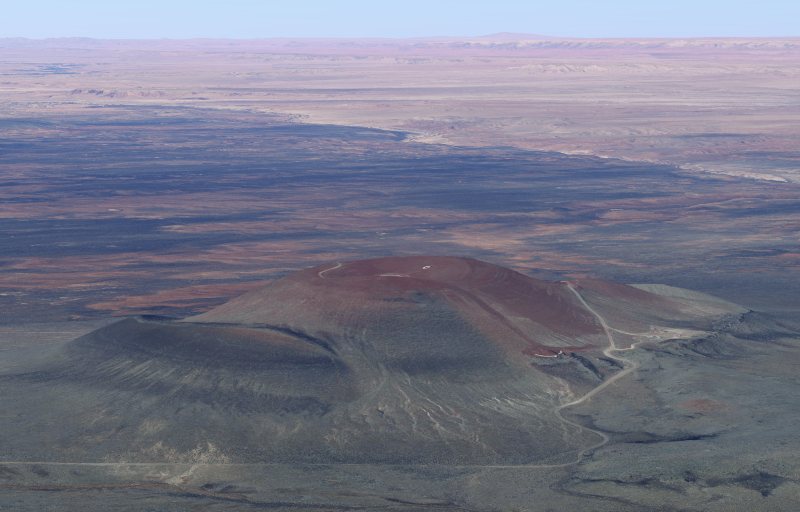

*The photo is of James Turrell’s Roden Crater and is mentioned in my post for the Irvine Foundation. (Here’s the link again!)

[contextly_auto_sidebar]