[contextly_auto_sidebar id=”BCkhv504PNyMLqaIFc3XpLPZvWwm0Kcs”]

A couple months back I was asked to give a talk on civic leadership to a group of arts leaders participating in the fantastic UK-based Clore Leadership Programme. We tend to take for granted that subsidized arts organizations are, by default, key players in civil society–that is, civic leaders.

But are they?

I believe arts organizations can, and should be, civic leaders but that such a role will require that many organizations pursue a different relationship to their communities.

What follows is an excerpt/adaptation from the full talk.

In their article, Thinking About Civic Leadership, David Chrislip and Edward O’Malley convey that in the nineteenth and early-to-mid-twentieth century what generally was meant by civic leadership in America was “those at the top organization levels†that were “part of an elite, guiding force for civic life.â€[1] In other words, a network of white powerful men who knew what was best for their communities, and had ability to get things done. They operated from a position of authority, the authors write, doing things for their communities without input from their communities-at-large.

Among the institutions such civic leaders advanced, in the US, was the arts and cultural sector: museums, symphony orchestras, opera companies, ballet companies, and eventually regional theaters. This was the era in which private foundations and governments alike justified and promoted such investments on the basis of the ideals of “excellence and equity,†–by which they meant, generally, access for everyone to the art deemed most important by those vested at the time with the power to decided what counts as art.

But Chrislip and O’Malley also suggest that this view of civic leadership—a view that granted power for a small group of elites to control the lives of everyone else—began to be challenged in the 60s and 70s with the emergence and impact of the civil rights movement, the environmental movement, the women’s movement, and other grassroots social movements.

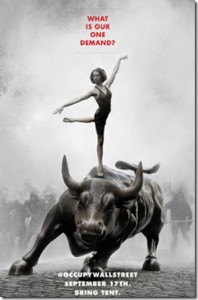

In fits and starts, as movements have emerged, gone underground, and re-emerged, over the past 30 years ideas about what is meant by civic life and who gets to participate in it have been challenged and slowly redefined–most recently in the US by such events as the Occupy Movement.

And today, we are living in “a civic world turned upside-downâ€â€”an era in which citizens with the freedom and means by which to access the Internet have the tools to more easily self-organize, mobilize, express their concerns and desires to a global audience, and thereby participate in the civic world (if by that we mean the relationship of citizens to each other and to government) and potentially influence the political decision-making process.[2]

Is this civic world upside down a good thing for the arts?

Our first instinct may be to shout, “Of course!â€

But let’s be honest: The old civic world worked pretty well for the fine arts.

We (meaning established arts organizations and their patrons) were among those with authority to dictate what counts as art and culture. Leading in the new civic world is not about dictating what counts as art. Instead, it would seem to require a willingness to relinquish authority; to open up our institutions for citizen engagement, not just in artistic experiences but in governance; to look beyond the preservation, advancement, and interests of our individual organizations; and to use our many assets to serve the larger needs of society.[3]

Indeed, this seems to be one of the grand narratives in the arts these days.

It’s the narrative that tells us that we need to rethink our relationship to the world, come down out of the ivory tower, and work side-by-side with our communities to improve quality of life for all citizens in the places where we live. But there is another narrative that has been exerting a powerful gravitational pull in the opposite direction. It’s the narrative that tells us that the path to salvation is a whole body embrace of the power, wealth, and financial growth at all costs. And in this civic world turned upside down, it seems it is becoming increasingly difficult to manage the tension between these competing narratives. As an example, Mark Ravenhill’s speech at the Edinburgh festival last year highlighted, in particular, the way that the means of some subsidized arts organizations may be in conflict with their supposed ends.

He said:

I think the message in the last couple of decades has been very mixed, in many ways downright confusing: we are a place that offers luxury, go-on-spoil-yourself evenings where in new buildings paid for by a national lottery (a voluntary regressive tax) you can mingle with our wealthy donors and sponsors from the corporate sector and treat yourself to that extra glass of champagne but we are also a place that cares deeply about social justice and exclusion as the wonderful work of our outreach and education teams show. So we’re the best friends of the super-rich and the most disadvantaged at the same time? That’s a confusing message and the public has been smelling a rat. If the arts are for something, who are they for? And what are they doing for them?[4]

The question is being called. What’s the answer if we dig down deep and answer truthfully?

Do we want to be country clubs? Or do we want to be civic institutions?

Ronald Heifitz, the Harvard professor who has led the research agenda around adaptive leadership in the US tells us that the complexity of the ever-evolving challenges in the new world require different, even “unorthodox†responses to make progress. Our status quo has to be disrupted. This means that we need to confront the things we take for granted, including all the attachments we have to our world view. This inevitably entails the loss of our sense of identity, status, and values.[5]

And, as Clay Shirky tells us in his TED Talk, Institutions vs Collaboration, institutions are no different from humans in that if they feel threatened they seek to self-preserve.

Have you noticed that there has been a recurring theme to arts conferences the past five years: How do we survive? How do we thrive? How do we build resilience so we can bounce back? How do we find innovative ways to, essentially, sustain the infrastructure and institutions that we’ve created over the past 100 years?

I’ve asked many of these questions myself.

But what are we trying to sustain, to preserve? Ourselves and our once privileged position in an elite-dominated civic world? Or something that transcends ourselves and our organizations? As the person who wrote a talk a few years back called Surviving the Culture Change, I am here to say I think we need to move on from the narrative in which we are primarily concerned with the surviving and thriving of our individual organizations.

On Civic Leadership

And this, really, brings us to the notion of civic leadership. How shall we conceptualize civic leadership? How is it different from other types of leadership?

Here’s the vision from Chrislip & O’Malley:

Rather than a ruggedly individualistic pursuit of our own ends, we might demonstrate care and responsibility for the communities and regions in which we live. Instead of limiting our conception of what civic responsibility means to that of a passive law-abiding “good†citizen activated only when our backyards are threatened, our first impulse would be to engage others to work across factions in the service of the broader good.[6]

In a similar vein, Mary Parker Follet writes on the topic of power and defines it as “the ability to make things happen, to be a causal agent, to initiate change.†However, Follet distinguishes between power over (power that is coercive) and power with (synergistic joint action that suggests we facilitate and energize others to be effective). The old civic world was power over. The new civic world is power with.[7]

And John W. Gardner writes that we need a network of leaders who take responsibility for society’s shared concerns and that the default civic culture needs to shift from a war of the parts against the “whole†to an inclusive engaging and collaborative one that could make communities better for all.[8]

You can hear the common threads in these elaborations.

To achieve these ends two other scholars, leadership studies scholars Peter Sun & Marc Anderson, suggest that leaders need to add on to their existing skills in transformational and transactional leadership and develop what they call Civic Capacity.[9]

Civic Capacity is made up of three components:

- Civic Drive: Do you have the desire and motivation to be involved with social issues and to see new social opportunities?

- Civic Connections: Do you have the social capital (i.e., networks) to enable you to engage in successful collaborations with other organizations and institutions in your community?

- Civic Pragmatism: Do you have the ability to translate social opportunities into practical reality (i.e., what structures and resources can you leverage to make things happen)?

This is big, demanding work. Our first impulse may be to keep our heads down, to pursue the path of least resistance. While doing so may ensure that our grants continued to be renewed for the time being, it won’t ensure our future relevance or contribute to a better world.

Awhile back I read philosopher Martha Nussbaum’s book Not for Profit, Why Democracy Needs the Humanities, in which she makes the case for liberal arts education, and in particular the importance of the arts and humanities. In it she asks what abilities a nation would need to produce in its citizens if it wanted to advance a “people-centered democracy dedicated to promoting opportunities for “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness†to each and every person.[10] She answers with such things as:

- The ability to think about, examine, reflect, argue and debate about the political issues of the nation.

- The ability to recognize and respect fellow citizens as people with equal rights, regardless of race, gender, religion or sexuality.

- The ability to have concern for the lives of others.

- The ability to imagine and understand the complex issues affecting human life by having an understanding of a wider range of human stories (rather than just data).

- The ability to think about the good of the nation, not just one’s own group.

The arts have so much to offer to the advancement of such goals; but only if we step up to the work.

Change is needed.

Conclusion

Back in June, I went on a residential training with the organization Common Cause, which seeks to encourage NGOs and others working in the social sectors to join up to advance common values in society—values like A World of Beauty, Social Justice, Equality, A Meaningful Life.[11]

At the first gathering when we went around the circle and talked about why we had chosen to come on the training and I said something to the effect of:

I’m here because I’m trying to figure out what I’m laboring for that transcends arts and culture. I’m here because I feel like I’ve been talking in a closed circuit and I want to join up the conversation we’re having in the arts with the conversation others are having about the environment, or human rights, or education. I’m here because I don’t know if I can continue to work on behalf of the arts if the arts are only interested in advancing themselves.

I’m here because I’m worried about things like growing income inequality and suspect that growing income inequality may actually benefit the arts. And what are we going to do about that? I’m here because I’m worried about cultural divides and that the arts perpetuate them more than they help to bridge them.

I believe the arts could be a force for good, but I believe we will need to change as leaders, and as organizations, in relationship to our communities, for them to be so.

There is a challenge/opportunity before all of us.

I leave you with two final questions:

- What are you laboring for that transcends your organization and your position within it? What values, goals, or progress in the world?

- And what are you going to do about it?

***

[1] Chrislip & O’Malley 2013, p. 3

[2] Chrislip & O’Malley, p. 5.

[3] The theory of basic human values was developed by Shalom H. Schwartz and is the basis for a framework developed by the advocacy organization Common Cause. More information may be found in the Common Cause Handbook, published in 2011 by the Public Interest Research Center (Wales).

[4] Ravenhill, M. (2013). “We Need to Have a ‘Plan B’â€. Published in The Guardian 3 August 2013 and available at: http://www.theguardian.com/culture/2013/aug/03/mark-ravenhill-edinburgh-festival-speech-full-text.

[5] Chrislip & O’Malley, p. 7

[6] Chrislip and O’Malley, p. 11

[7] Chrislip and O’Malley, p. 7

[8][8] Chrislip and O’Malley, p. 7

[9] Sun, P.Y.T. & Anderson, M.H. (2012). Civic capacity: Building on transformational leadership to explain successful integrative public leadership. The Leadership Quarterly 23 (2012), 309-323.

[10] Nussbaum, M. C. (2010). Not For Profit: Why Democracy Needs the Humanities. Princeton: Princeton University Press. (See pages 225-26).

[11] Public Interest Research Centre (2011). The Common Cause Handbook. London: PIRC.