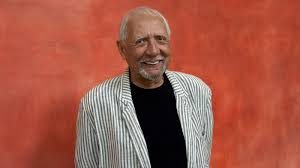

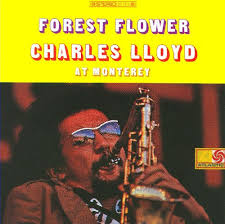

During the 50 years since his breakthrough album Forest Flower (released in February 1967, recorded live at the Monterey Jazz Festival the summer before) — comparable in some ways to The Epic success of Kamasi Washington – saxophonist-flutist Charles Lloyd has been unusually popular for an adventurous jazzman. He showed how he’s done that, accomplished a long career while expressing himself freely, with his on-tour Marvels at Chicago’s Symphony Center Friday night (4/21), and it’s worth unpacking.

Lloyd, 79, and his empathic, considerably younger quintet (guitarist Bill Frisell and pedal steel guitarist Gary Leisz are in their mid 60s; bassist Reuben Rogers and drummer Eric Harland in their late 30s) play instrumental, mostly improvised, sometimes dense and abstract music. At Symphony Center the ensemble was spontaneous and artistic, its members entertaining each other as well as the visibly diverse audience, casting a spell that entertained the merely curious as well as deep-dyed fans, across age and races.

The crowd (perhaps 1800 in a theater holding 2500) responded with such an ovation — and the musicians themselves seemed so delightfully energized — that an encore turned into a full second set, with guitarist Mary Halvorson, who had been in cellist Tomeka Reid’s quartet that opened the show, sitting in. (Reid, in full bloom with record releases and residencies, is a hometown favorite — just celebrated by the Jazz Journalists Association as Chicago’s 2017 Jazz Hero, and yes, I had a hand in that. She, Halvorson, bassist Jason Roebke and drummer Tomas Fujiwara performed original compositions that resolved their quirky lines and turns with satisfying repetitions). So here are aspects of Lloyd’s presentation and performance that have worked for him for decades, and might be considered for adoption or adaptation.

- Play with the best. Lloyd learned this early on — perhaps from his first nationally-known employer, drummer Chico Hamilton, who always hired distinctive sidemen (Buddy Collette, Jim Hall,

Paul Horn, Eric Dolphy, Fred Katz, Gabor Szabo, Larry Coryell). Lloyd proved he understood by assembling a band with then-obscure pianist Keith Jarrett, drummer Jack DeJohnette and bassist Ron McClure — whose careers were all launched by Forest Flower, too. Lloyd expects the contributions and interactions of his band members to follow from his leads and set up his solos. He selects them for imagination and deftness; they respond quickly, supporting his moves, free to pursue their own paths through grounds he’s laid out. His sidemen get it: in conversation backstage, Harland vowed that he only sounded good because the rest of the band made music so well. Over the years Lloyd’s collaborators have included pianists Michel Petrucciani, Bobo Stenson, Don Friedman, Cedar Walton, Jason Moran, Brad Mehldau and Geri Allen; drummers Billy Hart and Billy Higgins; bassists Dave Holland, Cecil McBee, Marc Johnson, Palle Danielson, Robert Hurst, Buster Williams and Larry Grenadier; guitarist John Abercrombie and percussionist Zakir Hussain. That’s a roll call of great listeners who play, each with something to say.

Paul Horn, Eric Dolphy, Fred Katz, Gabor Szabo, Larry Coryell). Lloyd proved he understood by assembling a band with then-obscure pianist Keith Jarrett, drummer Jack DeJohnette and bassist Ron McClure — whose careers were all launched by Forest Flower, too. Lloyd expects the contributions and interactions of his band members to follow from his leads and set up his solos. He selects them for imagination and deftness; they respond quickly, supporting his moves, free to pursue their own paths through grounds he’s laid out. His sidemen get it: in conversation backstage, Harland vowed that he only sounded good because the rest of the band made music so well. Over the years Lloyd’s collaborators have included pianists Michel Petrucciani, Bobo Stenson, Don Friedman, Cedar Walton, Jason Moran, Brad Mehldau and Geri Allen; drummers Billy Hart and Billy Higgins; bassists Dave Holland, Cecil McBee, Marc Johnson, Palle Danielson, Robert Hurst, Buster Williams and Larry Grenadier; guitarist John Abercrombie and percussionist Zakir Hussain. That’s a roll call of great listeners who play, each with something to say. - Choose memorable material, old and new, then mix it up. Lloyd inserted familiar if seldom performed melodies such as Beach Boy Brian Wilson’s “In My Room” (the saxophonist toured and recorded with the Beach Boys), Ornette Coleman’s “Focus on Sanity” and “Ramblin’,” and his own “Sombrero Sam” (from his album Dreamweaver, which preceded Forest Flower) in his set as if to punctuate his looser modal episodes. The bold themes caught the ear (and gave the players interesting basis from which to stretch); the sketchier passages drew us into deeper meditation. In the encore, as Halvorson’s

flurries of trebly, pearl-dry notes sparkling amid the sustained and pitch-bent tones of Frisell and Leisz and rhythm section pulsations, a field of tones unfurled like the introductory alap of a raga unfurled, implying to me the Beatles’ “Within You Without You.” Lloyd didn’t state that theme, but I recalled how he turned “Here, There and Everywhere” into a quasi samba on his ’67 album Love In. He ended the Marvels’ concert with a seriously sensuous rendition of “Prelude to a Kiss,” which Duke Ellington composed in 1938.

flurries of trebly, pearl-dry notes sparkling amid the sustained and pitch-bent tones of Frisell and Leisz and rhythm section pulsations, a field of tones unfurled like the introductory alap of a raga unfurled, implying to me the Beatles’ “Within You Without You.” Lloyd didn’t state that theme, but I recalled how he turned “Here, There and Everywhere” into a quasi samba on his ’67 album Love In. He ended the Marvels’ concert with a seriously sensuous rendition of “Prelude to a Kiss,” which Duke Ellington composed in 1938. - Have fun, don’t fear rhythm. Lloyd kept the music moving, aided immensely by Rogers and Harland, of course. Jazz bass-and-drums teams today are often busy and seldom rigid — they want to be able to turn immediately to any option, so they may lay down a grooving backdrop rather than establishing and emphasizing one identifiable beat (unlike most hip-hop, say). Onstage but off-mike, Lloyd was unobtrusive but attentive to the set’s overall rhythm — percussion accents, ensemble tempos, flowing pace — at Harland’s side shaking rattles when he felt the need. Sensing his players’ climaxes as they came on, he’d step out from behind them to pick up his tenor and blow. Playing his alto flute on what I’ve id’d as “Sombrero Sam,” he swung his hips like a cool beatnik at a dance club. Being in the moment, unselfconscious, with the music, Lloyd inspired his musicians and listeners alike to do the same.

Not everyone can project the natural, perhaps innate feeling for jazz of Charles Lloyd. He’s had a singular background, which can’t be duplicated.  Claiming African, Mongolian, Cherokee and Irish ancestry, from age nine he showed interest in jazz and pursued his opportunities, hearing swing-to-bop on the radio (Lester Young’s airiness survives in Lloyd’s sound and phrasing), working in commercial r&b/blues bands. Hometown associates included trumpeter Booker Little, pianist Phineas Newborn and tenor saxophonist George Coleman, now also an NEA Jazz Master.

Arriving at University of Southern California when he was 20 to study with a Bartok specialist, Lloyd fell in with Ornette Coleman’s circle and joined Gerald Wilson’s Orchestra. In bands led by Hamilton (in ’60) and Cannonball Adderley (’64), he observed progressive ideas presented in accessible formats, and pursued the search for new/ancient “world” music pioneered Yusef Lateef and John Coltrane. He was 30 during the Summer of Love,  and Forest Flower was a breezy, lyrical, high energy album embraced by hippies, promoting him quickly, internationally. That very year his quartet made an unprecedented tour of the Soviet Union — and from there to now, some down time but also many great steps in between. ((For more info, check out Josef Woodard’s biography Charles Lloyd: Wild Blatant Truth.)

Lloyd’s basic orientation has held. He has his own voice, amalgamated from many sources, filtered through his experience, perspective, personality, preferences and perhaps whims, but hewing to fundamental dictums. Perform with the best available collaborators, even if you have to discover them yourself. Select songs people will remember — and you don’t need to have composed them all. Play the music, from within, keeping in mind that there are listeners you want to attract and satisfy. Keep the music moving. Live long and with a little bit of luck prosper. Don’t take your too seriously, and yet. . . Emerging from dressing rooms after the performance, Lloyd commented dryly on the multiple nominations (Lifetime Achievement in Jazz, Musician of the Year, Mid-Sized Band of the Year, Tenor Saxophonist of the Year) he’s received for 2017 JJA Jazz Awards: “Maybe I have some potential.”

howardmandel.com

Subscribe by Email |

Subscribe by RSS |

Follow on Twitter

All JBJ posts |