The deathbed wish of composer-cornetist Lawrence Douglas “Butch” Morris (1947-2013) was  that his detailed documentation of Conduction®, the method he devised to enable spontaneous composition for ensembles of literally any type employing codified hand-signals, be published in hardcover. This has come to pass. On April 24 and May 1, events in New York City will launch The Art of Conduction, an elegant workbook from art-world publisher Karma with photos of Morris and his text, making his innovative work available for use by anyone/everyone, regardless of previous musical background.

that his detailed documentation of Conduction®, the method he devised to enable spontaneous composition for ensembles of literally any type employing codified hand-signals, be published in hardcover. This has come to pass. On April 24 and May 1, events in New York City will launch The Art of Conduction, an elegant workbook from art-world publisher Karma with photos of Morris and his text, making his innovative work available for use by anyone/everyone, regardless of previous musical background.

After his untimely demise a core coalition of friends and admirers of Butch (I was both, initially as a journalist, eventually as a neighbor, sometimes hanging out) as well as his son Alexandre rallied to produce his book, and they are celebrating its limited-time availability (small print run, reprinting not assured). The book, 224 pages of writings, photos and illustrations, will debut April 24  (5:30 pm) at Tilton Gallery on Manhattan’s upper east side, introduced by its editor Daniela Veronesi, professor of linguistics at Free University of Bolzano, Italy, and Alessandro Cassin, who guided it into print. Butch’s great friends saxophonist David Murray and trombonist Craig Harris, with bassist Melissa Slocum, will be there to perform Harris’s “The Original LA Dawgs” (Butch Morris was born and raised in Long Beach. Harris employed basic techniques of Conduction® in his piece “Breathe,” performed at 2017 Winter JazzFest).

On May 1, guitarist Brandon Ross, cornetist Graham Haynes, bassist Stomu Takehishi and sound designer Hardedge will perform at 5:30 at Karma Gallery in the East Village –Morris’ old stomping grounds — where Black February, Vipal Monga’s film about Butch will be shown,

Veronesi and Cassini again on hand with the book. At 9 pm at the cozy club NuBlu Ross and Haynes will join the NuBlu Orchestra, which Morris conducted in two recordings (two, big fun both). Poet Allan Graubard, whose writing appears in The Art of Conduction, will read at both May 1 events.

I’m quite proud of having written the preface to The Art of Conduction — that essay caps my coverage of Butch Morris going back to a Village Voice article in the 1980s, pieces in DownBeat and Ear magazine, two NPR reports and a chapter in my book Future Jazz. To provide further context for Butch and the book, here are some excerpts from that chapter, which also involves David Murray and Henry Threadgill, another of Butch’s running buddies (2016 Pulitzer Prize for Music winner-Threadgill’s 2017 album Old Locks and Irregular Verbs is his stunning tribute to Morris).

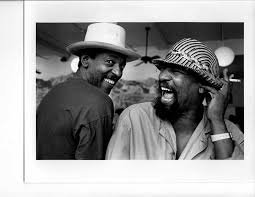

Murray and Morris met in California in ’71, as youngsters in drummer Charles Moffett’s rehearsal band. Morris was then playing cornet in the era’s open-ended jazz idiom, though his sound had the coloristic sensitivities of a lyrical rather than technique-oriented, brassy virtuoso.

Morris picks up his horn less frequently in the ’90s, but when he does he’s apt to spin the instrument backwards and jam its mouthpiece into its the bell, or turn it upside down to whistle across the holes at the bottom of the valves. He’ll try anything his curiosity suggests. He’s manufactured music boxes to showcase one of his jewel-like tunes; he enjoys the high-wire exposure of an acapella cornet concert; he’s played brass duets with J. A. Deane on electrically modified trombone and recorded atmospheric trios with keyboardist Wayne Horvitz (who uses advanced electronics) and drummer Bobby Previte.

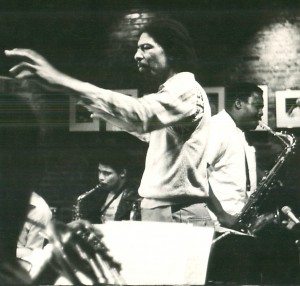

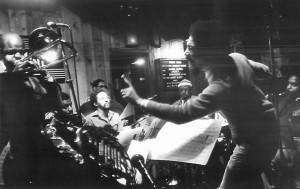

Conducting David Murray (right) big band w/ Steve Coleman (seated) – Sweet Basil’s, Greenwich Village, circa 1984, photo by Lona Foote

However, since the early ’80s, Butch Morris has liked best of all to hone a role he created for himself: improvising conductor. Audiences may now recognize him best from behind. His hair, thinning at the crown, rises in front to a dramatic peak; his thin shoulders tense; his left hand, and the baton in his right, lift to focus the attention of the musicians before him. He stands ready to make music from a few scribbled measures—or none at all—the quick wits of his players and what appear to be charade gestures, the syllables of his language of conduction.

Morris didn’t pull the concept of conduction fully formed out of the thin air; he’s got a conventional jazz musicians’ background. He grew up in Watts amid music; his father, a career Navy man, had swing and big band records and liked to visit Johnny Otis’s club in their neighborhood. His mother helped him at the piano. His older brother Wilbur (now a bassist for David Murray and with his own quartet, Wilberforce), was originally a drummer who kept up with bop, ’50s funk, and the new(er) thing. Butch’s sister brought home Motown singles. At dinner together the family listened to a radio show that offered “bebop to boogie, rhythm and blues and rock ‘n’ roll.”

He followed the public school music curriculum, and benefitted from dedicated teachers with high standards, including saxist Charles Lloyd who taught a music appreciation class. . . Morris made the school orchestra and after-class sessions; he wigged out on the Miles Davis-Gil Evans version of Porgy and Bess, and “before I got out of high school I’d taught myself flute, french horn, trombone, and baritone horn—I was still playing trumpet in the marching band, orchestra, and studio band, too—while at home I taught myself the mechanics of piano. . .”

from left: Craig Harris, trombone; Roy Campbell or Graham Haynes cornet?; Jack Jeffers? tuba?; Edward Blackwell drums?; Ken McIntyre alto sax, Butch Morris conducting, David Murray, tenor sax; photo by Lona Foote

[After serving in the US Army as a driver in Germany and medic in Viet Nam] Morris got involved with Horace Tapscott, whose influence in the black community of Watts parallels that of Muhal Richard Abrams on the South Side of Chicago. “It had crossed my mind when I was in the service that I was creating a personal way of improvising,” Morris remembers “and I had to find the environment in which I could improvise best. I wasn’t a bebopper, I wasn’t a post-bopper and I wasn’t a free-bopper, so I had to create the environment. My development of it didn’t start until later, but in his band Horace used to make little gestures that meant certain things for us to do that weren’t on the page, and I started to think about how that could be expanded.

“In ’70, ’71 I decided this is it. I started putting music down on paper, calling up cats, and saying, ‘Come on, let’s rehearse,” and they’d say, ‘Oh, I can’t, groan’—and I’d go physically get the cat because unless I did I was never going to hear how these ideas of mine sounded.” As he became serious about music, he wearied of Los Angeles. “Sooner or later you come to grips with working and whether you have something to offer or not. You go where you can work and be recognized.” Morris went north.

“When I was in college, studying conducting in Oakland, and I asked my teacher ‘How do you get the orchestra to go back to letter B?’ and she said, ‘You don’t do

that,’ I knew I had a profession. But basically, I got the idea of conducting improvisation from Charles Moffett,” the Fort Worth-born and -bred drummer best known for his association with Ornette Coleman. . .

“Charles would lead his ensemble rehearsals with no music, he would just conduct, with a relatively underdeveloped vocabulary of gestures. I knew it could be taken further. Now, Charles is an energetic cat and what he did was musical, man. It was like: You—play. Now you—do what he’s doing.’ But he would never talk to us, it was all gestures. And I thought, ‘Damn, this is some interesting music. This is great. I’m going to pursue this.'”

. . . His emergence as a jazz conductor dates to the debut of David Murray’s big band, which the late Public Theater producer Joseph Papp encouraged to form in ’78. Initially helping Murray compose and orchestrate for that concert, Morris soon stepped in front of the big band to “create music on the spot” with a gestural vocabulary he used to satisfy a desire for instant decision-making that few jazz arrangers have ever been able to indulge. . .

“I see all my activities working together, but it takes a while,” says Morris, who sports a wispy Fu Manchu goatee. “First of all, change, diversity and variety are central to my nature, and secondly, I use them for my livelihood.

“I compose whatever my little heart desires,” Butch claims. “But I’m not meandering. I’ve got a goal: My whole idea is to create music for improvisers. I like to bring together people who might not necessarily play with each other, or who play in different styles and improvise in completely different ways. I rarely write, that is, notate, everything. I get tired of playing the same arrangements so I constantly re-arrange tunes to figure out their other harmonic and tonal possibilities. I’d hate to work with a band for three years and always play the same charts. I mean, even [Duke Ellington’s] ‘Take The A Train’ varied over the years. . .

at the Akbank Festival in Istanbul, Butch conducted an ensemble including ney virtuoso Sulieman Ergüner and his ensemble of Sufi musicians

“There’s a history for improvisers, a body of common knowledge among jazz musicians,” Morris states. “There’s a whole repertoire of songs that have been used as a basis for improvisation, like the blues. We can just call a key, and it doesn’t have to have a name—we can make music, right? Well, if I point to you, and you’re an improviser, and as part of my vocabulary you understand that when I point to you you’re supposed to improvise—that’s a beginning. You play until I ask you to stop. And if I hear something that you play that I want you to repeat or develop, I have a gesture I’ll give you for that. If I want you to continue on that same frame on a longer curve, I have a gesture for that. If I want someone to do or emulate something that you’re doing, I have a gesture for that. It continues to grow, my vocabulary for improvisers.

“I have to figure out how to get the best from an improviser, put them in that light, then start to push them in another direction and see how flexible they are. A lot of improvisers are not flexible. They know how to improvise in a particular style, but they don’t venture too far from that style. . . .

“Through my gestural vocabulary the improvisers and audience start to hear the music happen. You don’t just hear the music happen, you start to hear it happen, and then all of a sudden, it happens.

Having taught his vocabulary to the clique of jazz improvisers David Murray drew on (some of whom have become aspiring composers themselves), after the big band’s concert at the New York Kool Jazz festival of ’85 Morris determined to concentrate on less tune- and solo-oriented, more suite-like and ensemble applications of his gestural direction, involving instrumental combinations of his own design. On February 1, 1985, at the Kitchen Center for Music, Video and Dance, he created what he considers a historically important “full conduction, which is an improvised duet between ensemble and conductor based on subject matter, in which the conductor works out his gestures and relays them to the ensemble, and the ensemble in turn interprets the  gestural information.”

gestural information.”

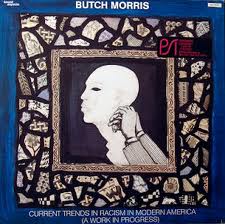

I’ve written at length about Current Trends in Racism in Modern America, A Work In Progress, “my first attempt to have a full conduction in the United States,” Morris called it, proudly. And that’s not the point here: The Art of Conduction is.

Butch Morris from Long Beach always took a long view. When he was around 40, he said, “If I’m not reaching for something as powerful as my heritage has been—” he considered Ellington, Fletcher Henderson, Count Basie and Jelly Roll Morton among his predecessors as improvising, composing, conducting instrumentalists—”then it’s not going to be meaningful in the long run. I want to create something as powerful as my heritage, and something very magical at the same time.”

Morris’ music had the magic, as its recordings preserve (most abundantly on Testaments, a 10 CD set 16 highly varied full conductions, with Butch’s extensive written commentary). Now we’ve got a book that crystalizes his concept – his bid to contribute powerfully to our heritage.

It is a difficult and remarkable thing to sustain much less extend the works of an innovative artist beyond their lifetime, requiring the desires and resources of their survivors, beyond any perceivable valuations of the artist’s output. Morris’s devotees have invested themselves in his legacy out of a lot of love but The Art of Conduction is no vanity project. Morris conceived his book — which he carried with him in the form of notes that he worked on constantly — to be functional, not to be gazed upon but used, to make and change music (theater, dance, poetry, too). So add Conduction® as codified by Butch Morris to your skill-set. What you do with it will be your own. It may be ordered in individual or bulk quantities at orders@artbook.com.

howardmandel.com

Subscribe by Email |

Subscribe by RSS |

Follow on Twitter

All JBJ posts |