from left: Jim Pugh, Ricardo Flores, Glenn Wilson, Armand Beaudoin at The Normal Theater; photo by Jeff Machota

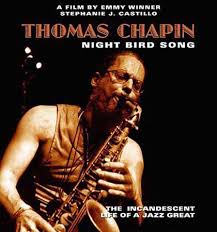

Glenn Wilson, a terrific baritone saxophonist and flutist based in Normal, IL, is also a major mensch. Last Saturday, at the end of Normal’s Sweet Corn and Blues festival, he organized a free concert and screening of Thomas Chapin: Night Bird Song, a comprehensive documentary about his friend, the usually exuberant alto saxophonist, flutist and composer who died of leukemia at age 40 in 1998.

I was invited to lead a post-screening discussion with director Stephanie J. Castillo, who Skyped in from Brooklyn to The Normal Theater. Hear our discussion here.

Bloomington-Normal are twined cities of some 130,000, home to State-Farm Insurance as well as Illinois State University and Illinois Wesleyan University, where Wilson is newly appointed jazz director. It’s about 125 miles southwest of Chicago. Wilson makes the relatively fast drive up and back frequently, sometimes to play on a Monday night at the Serbian Village. But his connections with Thomas Chapin go back to the late ’70s, when as students at Rugers’ Livingston College they were both in professor Paul Jeffrey’s band. Both joined Lionel Hampton’s touring outfit in the 1980s. They stayed close. Wilson treasures Chapin’s music.

from left: Dorothy Matirano, Ricardo Flores, Adriana Ransom, Armand Beadoin at The Normal Theater; photo by Walter AlspaughChapin’s music.

In 2012, 14 years after Chapin’s death, Wilson re-arranged and recorded several of pieces from Haywire, Chapin’s 1996 album for his trio supplanted by a second bass and cello. Wilson’s versions are heard on The Devil’s Hopyard by TromBari, the ensemble he co-leads with trombonist Jim Pugh. At The Normal Theater, TromBari — featuring violinist Dorothy Martirano, cellist Adriana Ransom, bassist Armand Beaudoin and drummer/percussionist Ricardo Flores — performed finely detailed yet hard-swinging parts that opened to rugged solo and group improvs. They did a rousing set before the theater darkened for the 150-minute version of the film (which Castillo is currently editing down to 90 minutes — she also has a four hour “director’s cut”) and returned for a brief blowout during an intermission. About 150 Central Illinois music devotees, some from as far away as Champaign (55 miles) and Peoria (40 miles), gathered for the event focused on a musician who had never toured the region and whose many, varied albums recorded for small independent labels are rare and/or out-of-print. Thomas Chapin’s sister and brother-in-law drove from Chicago — the same trip took me about three hours — in order to see Night Bird Song on a big screen for the first time.

Night Bird Song, like Wilson’s evening-long, grant-supported screening/show, is a labor of love. Castillo, an Emmy-winning film-maker, was Chapin’s sister-in-law, but knew little about his music or the downtown New York scene he enlivened until after his demise. Having done deep research, she has made a thorough job of tracing Chapin’s musical life from its earliest glimmerings through his posthumous album releases, including interviews with such of his important collaborators as bassist Mario Pavone, drummer Michael Sarin and saxophonist Ned Rothenberg and great live performance footage.

Here’s Chapin, age 26, blowing the blues while Hampton, 84, bounces behind his drums. Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â

Here’s Chapin highly charged at the Knitting Factory, winning over fans in Europe, spellbinding at the Newport Jazz Festival. Here’s Chapin in his down time, floating like a smiling angel with full appreciation of the world about him, whether he’s in gritty Manhattan, on beautiful beaches or in East Africa, where he was suddenly stricken with his fatal disease.

Sad though it was and is that Thomas Chapin died so young, possibly on the cusp of a career breakthrough, it is heartening that friends like Wilson, Pavone, the Knitting Factory’s Michael Dorf, Festival Production’s Danny Melnick and of course Castillo herself have created such a rich and engrossing portrait of the artist. A film of this sort — which won the Best Story award at the Nice International Filmmakers Festival last May, and which will be shown at the Monterey Jazz Festival on Sept. 17 — provides significantly more proof of its

subject’s life, spirit and times than, say, a DownBeat article or a Wiki entry. Rather than being about a salacious, outlaw sort of jazz figure, it focuses on a man who lived to make music he could proudly claim was “pure.” I remember Thomas onstage, and in person — he was typically aglow with delight. See Night Bird Song when it’s near you for exposure to a man’s sweetness and soulfulness, the likes of which inspires people such as Glenn Wilson and his TromBari colleagues to keep working, teaching, playing beautiful sounds for everyone who will listen.

subject’s life, spirit and times than, say, a DownBeat article or a Wiki entry. Rather than being about a salacious, outlaw sort of jazz figure, it focuses on a man who lived to make music he could proudly claim was “pure.” I remember Thomas onstage, and in person — he was typically aglow with delight. See Night Bird Song when it’s near you for exposure to a man’s sweetness and soulfulness, the likes of which inspires people such as Glenn Wilson and his TromBari colleagues to keep working, teaching, playing beautiful sounds for everyone who will listen.

howardmandel.com

Subscribe by Email |

Subscribe by RSS |

Follow on Twitter

All JBJ posts |