My profile of Pulitzer Prize winner Henry Threadgill, commissioned by and published in DownBeat in 2010:

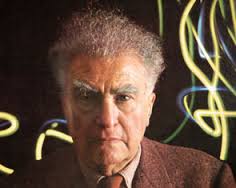

Henry Threadgill exuded confidence and impatience when facing four video cameras and a standing-room-only gallery of serious listeners at the Manhattan new music performance space Roulette last October. With his flute, bass flute, alto saxophone and bass clarinet at hand and the members of his ensemble Zooid — guitarist Liberty Ellman, tuba-and-trombonist Jose Davilla, fretless bass

Roulette TV: HENRY THREADGILL // ZOOID from Roulette Intermedium on Vimeo.

guitarist Stomu Takehishi and traps drummer Elliot Humberto Kavee — stationed around him, he was about to plunge into the premier of music from his first album in eight years, This Takes Us To, Vol. 1. The cameras would capture it all for eventual cable broadcast and online viewing via Roulette TV.

Threadgill’s gaze was steady, his expression tight-lipped, his posture upright. Advance review copies of This Takes Us To had already created a buzz, which is why the aficionados had gathered, wondering “What is Threadgill up to now?”

For more than 40 years, the Chicago-born reeds specialist has ventured repeatedly beyond established frontiers of composition and improvisation. At age 65 he remains energized, astute and  ambitious, ignoring musical conventions and classifications to focus on music itself. He takes nothing for granted, probes the basics and comes up with ideas as startling as his sound. He lives by example, making music to satisfy his own boundless curiosity, though he says, “I play what I hope is spiritual music for the higher aspects of people’s existence.”

ambitious, ignoring musical conventions and classifications to focus on music itself. He takes nothing for granted, probes the basics and comes up with ideas as startling as his sound. He lives by example, making music to satisfy his own boundless curiosity, though he says, “I play what I hope is spiritual music for the higher aspects of people’s existence.”

What Threadgill and Zooid (a biological term for an organic cell that moves independently through the body it’s within) offered in concert was richly textured group interplay, organized pieces rife with virtuosity and passion — but few familiar touchstones such as obvious melody, chord progressions or head-solo-solo-solo-head structures. The band clearly had a plan but its goals were elusive, its comforts few, its points resistant to quick assessment. Maybe that was the point.

Each piece began airily, with Davila’s softly burred or limpid tuba tones, Takeishi’s fretless bass guitar figures or Ellman’s light-fingered plucks and strums underscored by Kavee’s loose, louche rhythms. Threadgill, sheet music on a stand before him, concentrated on the activity, ears perked, body sometimes bending to a passage, pleasure occasionally flitting across his face.

Zooid — from l., Liberty Ellman, Jose Davila, Henry Threadgill, Stomu Takehisi; photo c 2010 by Robert Klurfield

The other musicians’ gestures — layered but shifting, rather than clearly integrated or synchronized — gradually accumulated. Then Threadgill leapt in on flute or sax with short, insistent phrases, quick runs of adjacent notes or single pitches urgently repeated. He seemed like an Old Testament prophet decrying vanities and illusions from a windswept plateau. The ensemble flowed in subversion of customary instrumental hierarchy: sometimes Ellman preceded and sometimes he echoed Threadgill, sometimes he paired with Takeishi or fenced with Davila or flew off on his own. Kavee mostly maintained a steady pulse, smiling softly as if enraptured by a symphony in his head.

No song titles were announced (too bad: they’re brain-teasers) or words said except the players’ names. The overall ambiance was mystery, foreboding and confrontation. “I’m not playing to entertain,” Threadgill asserted a couple of weeks later, unusually chatty over a latté at an Italian pastry shop near the apartment in New York City’s East Village where he’s lived in since moving from Chicago in the late ’70s. “That means I don’t have to play anything pretty, or something that’s not challenging you. It can send you out the door, and that’s fine, too, because it might stay with you and make you think of something much later. My music’s not about your immediate reaction to what I’m doing, but what it’s doing for you and to you. That’s my hope.”

Since emerging in the late 1960s as one of the individualistic first generation members of the AACM (Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians), Threadgill has continuously challenged listeners and also other musicians with his investigations of the structures, practices and implications attending jazz and contemporary composition. He’s recorded some 30 albums on major labels and tiny independents, under his own name or, in the 1970s and ’80s, with the trio Air. He’s collaborated on nearly that many with AACM compatriots Muhal Richard Abrams, Roscoe Mitchell and Douglas Ewart, as well as David Murray, Bill Laswell, Kip Hanrahan and the reggae rhythm team Sly Dunbar and Robbie Shakespear. He’s gained international esteem if not household-name fame or fabulous wealth, about which he doesn’t much care.

Far from content or complacent, Threadgill is inherently skeptical. His self-motivated studies have resulted in unusual insights. He’s a visionary and seeker, pushing ahead to get to the bottom of things. He hasn’t often explained the details of his concept, which he described as akin to serialism, using pitch intervals and freedom in their manipulation instead of single notes in a predetermined and fixed tone row. During a wide-ranging conversation, he cited Edgard Varese, Béla Bartok and Igor Stravinsky as inspirations. They don’t negate his identity; he is a jazz musician. “I don’t like that term, though. We’ve lost the meaning of it. So I say I’m doing creative music.

“The kind of music I’ve been writing for a long time is modular. Like this,” he demonstrated, piling two saucers on top of each other, as if crowning checkers pieces. Then he removed the top one and set it on the other side of the bottom saucer than where it had been when he’d started. The coasters represented intervals, not chords (“Because one of the things I went back to thinking about is ‘What is harmony?'” he asserted, “and found it’s any three notes, not three certain notes”), or episodes of written material (“Because there’s no rule that all you can improvise on is chord changes. We improvise on form”).

“See, both modules are still on the table. This one can be over here or this one can be over there. That’s a form of order. You’ve got to start with some kind of order, though it doesn’t really matter what order. I come into a rehearsal with this first order, which we play, and from there get to work on what’s going to be the first arrangement.

“Arranging these intervals is not just a process of moving things around on paper,” he said. “It includes interactive, spontaneous collaboration, because ideas come from the musicians about opening up or shortening sections and other processes. But all changes come about from the order of intervals I’ve brought. We work through it once and then do it again, dropping what we did and starting all over.

“In other words, first there’s this set of intervals, then this set of intervals, then this set and so on. Everything that happens melodically, harmonically, and counterpoint-wise is a result of the intervals, which are in existence for a specified length of time. When the improvisation part comes up, the same process is applied. It creates a gravity field. If you break it by playing something that doesn’t fit, you throw confusion into the air.

“In other words, first there’s this set of intervals, then this set of intervals, then this set and so on. Everything that happens melodically, harmonically, and counterpoint-wise is a result of the intervals, which are in existence for a specified length of time. When the improvisation part comes up, the same process is applied. It creates a gravity field. If you break it by playing something that doesn’t fit, you throw confusion into the air.

“I’m doing this so musicians won’t play all the contrived stuff that they’ve been taught and that they’ve heard in the chord progressions people play all the time. I want my musicians to play  spontaneous ideas. The only way to get them to do that is to get past the usual cues. Get rid of them, and there’s nothing to depend on. No C7, no D-minor mode. All you’ve got is intervals.”

spontaneous ideas. The only way to get them to do that is to get past the usual cues. Get rid of them, and there’s nothing to depend on. No C7, no D-minor mode. All you’ve got is intervals.”

Threadgill sat back, took a question and responded with further explication of his alternatives to standard methodology. He made sense of the sort that’s more understandable when its substance is heard than when it’s spoken of. His logic and theory are hard to deduce from the music they produce, but the richly detailed, densely active and utterly unpredictable music that Zooid has achieved after a year in private rehearsal following a decade of initial association has compelling drive, suspense that holds one’s attention and satisfactions that arrive as surprises.

“There is a system and there is no system,” Threadgill maintained. “It’s a natural language. It’s not some kind of theoretical stuff. It’s nothing artificial. The regular language of music is still there. I haven’t done anything to get rid of anything — I don’t believe in that. Anything that’s been very, very good you don’t get rid of it. You’d have to be crazy to get rid of what works. You’re supposed to find a way to condense it, reevaluate it, give it a new look, and keep its essence so you can come in with new information. It usually takes hundreds of years to come up with something that works: This is a verb in writing, or this is a way to create shadow or perspective in drawing or painting. You keep it, but you find another way to do it. I keep everything.”

Everything, for Threadgill, encompasses his history of investigations and transformations. In Air with the late drummer Steve McCall and late bassist Fred Hopkins he re-conceived customary trio strategies and abstracted pieces by Jelly Roll Morton. On X-75, his debut as a leader in 1979, Threadgill had three other winds/reeds experts, four bassists and a vocalist. In 1981 he introduced his seven-piece Sextet (later spelled with a second ‘t’), counting two traps drummers as one, and eventually added cellist Diedre Murray to pivot between the frontline of reeds/winds, cornet and trombone and the rhythm section. In the mid ’80s he began employing tuba players to shore up high, middle and low registers.

He kicked off the ’90s with Very Very Circus featuring two electric guitarists and two tubaists, to which he added a french horn. He lent himself to Laswell productions that flew in parts by members of Parliament/Funkadelic, vibist/arranger Karl Berger, Herbie Hancock, Wayne Shorter, Brazilian songman Carlinhos Brown and the drum band Olodum. He has written for string virtuosi including the AACM’s Leroy Jenkins, oud player Simon Shaheen and Chinese pipa player Wu Man, vocalists Cassandra Wilson and Asha Puthli, cylindrical Venezuelan drums and Cuban emigré drummer Dafnis Prieto, accordionist Tony Cedras, a cello trio, flute quartet, Talujon Percussion Ensemble, his own 20-piece Society Situation dance band and the Brooklyn Philharmonic.

Threadgill’s music is variously and sometimes simultaneously airy and lowdown, high powered and

suspended in time. His voice on alto sax has always been urgent but measured: he doesn’t blow streams of notes for volcanic affect. On flute, he articulates rather huskily exactly what he intends to, nothing superfluous. This is a composer-improviser who knows his mind, and plays it. He is capable of daunting complexity, with urban blues at its core.

“Every time I moved from one group to the next, my language was changing every time,” he claimed. “I never wrote music for the Sextett the way I wrote when I was in Air — I used completely other abilities for what I was doing with melody and form. From Air until Make a Move [his band from the ’90 to 2001] is all in the range of major-minor, and it broke over into chromaticism. I didn’t get out of that world until Everybody’s Mouth is a Book [the first session he completed in 2001] — there are three pieces in that in the new language. Make a Move was as far as I could go with major-minor music, then I mixed in chromaticism and whatever else I could think of until I got completely over to where I am now, to a complete language that has nothing to do with that.”

Threadgill credits Varese’s music for his epiphany about modular development. “I saw a process in what he was doing. He called it folding and enfolding. I was looking at that for about five years, I couldn’t get past it. But then one day I was sitting in my house in India [Threadgill has a home in Goa], looking again, and realized there’s more you can do with it. He wasn’t after what I was after. He got what he wanted by taking one step, where there were actually four or five steps. I don’t know if he knew about those steps, I never saw what I’m doing in his music, but everything I’m doing comes from that one thing he was doing, which was all he wanted to do with it. I went I’ll be damned, I’ve been sitting here five years and it’s right in my face. I’ve been going one-two, when there’s one-two-three-four.

“It’s funny: somebody tells you that’s a tape recorder. We sit here with it for weeks. Then I say, ‘I sure would like to hear the news or the ballgame on that.’ You say, ‘But it’s a tape recorder.’ We never even looked to find out if that tape recorder was a radio because we accepted the fact that this was a tape recorder. That’s the way everything is.

“We’re told that something is something, and we stay there. We never think to erase that definition from our minds and try to see this thing anew. When I did that I discovered what the Europeans said harmony was. Any three notes. They didn’t say thirds or fourths, they said any three notes. That’s what got me started, one of the ideas that helped me to develop this language. That and what I learned from Varese.

“I knew from Varese’s music, and Bartok and serialism that there was another way. A lot of people don’t like serialism, but that doesn’t matter, because it presents another order. Like if you think that there’s only French, then all of a sudden — ‘Wait a minute, there’s Korean, too?’ If there’s also Korean, there might also be Chinese or Argentinian or who knows what. Serialism, Varese, Bartok . . . I thought, ‘Wait a minute, how many other worlds are out there that are real, that you don’t have to contrive?”

How do other musicians relate to his new language? Asks one who speaks it. Guitarist Ellman first came to grips with the intervallic system as a sideman on Up Popped the Two Lips, the second of two sessions Threadgill committed in 2001. Interviewed at a Brooklyn coffee shop, he said his understanding is that “basically every chord has three notes, and the harmony moves among these triads — if you want to call them that. They’re more like three-note cells, because of the way the harmony functions. Henry takes the relationships of the intervals between each note in those triads, and he can generate six chords from that family of intervals. Those intervals are also what we use in terms of motion in the harmony and to inform us in our solos. You have to look at these interval sets and use them to help develop your motifs.

“In the past three or four years his compositions have become gradually more and more elaborate, with more pages, more sections and larger sections, also varying in how thematic the music is. He has a lot of different ideas about how to work with melody in terms of expanding or compressing the time, or playing one piece of a melody then jumping to another piece for improvising, then revisiting the next piece of the melody — which may be something the audience hasn’t even heard yet, but we musicians know how it’s related, so when we come back to it we have a certain energy for how we perform that section.“

Does this intervallic framework hamper improvisation?

“No,” Ellman said. “Though the forms are very elaborate and the harmonic structure, the rhythmic ideas are very specific to Henry’s written music, the intention is still as an improvised performer to interpret that music. When someone’s soloing, whether it’s you or you’re accompanying someone, the information you have from your jazz background serves you really well, because you’re still interpreting and using your intuition to play what’s best. If I’m soloing and I’m using Henry’s system on one of Henry’s pieces, there’s an interval set that I have to reference as if there’s a mode that went with the chords in that particular passage. I use that as a guideline, but I don’t have to only play that. Perhaps those intervals are featured more, or I use them to start an idea off of a chord tone, but then I can improvise using my ear the way any jazz musician does.”

Is playing that way a lot of work?

“To me it’s a good combination of the emotion and analytical,” Ellman continued. “The groove is always strong, you feel that infectious beat, and I find his melodies to be actually melodic and singable. They’re not necessarily simple, but they are motivic.

“Henry’s said to me he always wants there to be ecstasy in the music, that whatever we’re doing we need to reach these points where it’s immediate and emotional, raw. That’s how to resonate with the listener and yourself — through ecstatic statement. No matter how technical the music may get, it has to have that emotion, that power, in it. For him that seems to be second nature. He puts his horn in his mouth and there he is.”

What if you’re in the audience and not up to all this theory? Don’t worry.

“You can tell what’s working,” Threadgill himself suggested. “You’re not going to understand  everything theoretically, but you know it’s working, and you say, ‘How is it holding together?’ You know it is, you were sitting there, you heard it. It almost sounded like people were playing free, but they’re not. It’s freer than playing free. There’s so much harmony and counterpoint flying all over the place — isn’t there? You can’t predict when cycles happen, but we are playing cycles — melody, harmony and beat are developing as a result of my process, but we’re improvising on form, too.

everything theoretically, but you know it’s working, and you say, ‘How is it holding together?’ You know it is, you were sitting there, you heard it. It almost sounded like people were playing free, but they’re not. It’s freer than playing free. There’s so much harmony and counterpoint flying all over the place — isn’t there? You can’t predict when cycles happen, but we are playing cycles — melody, harmony and beat are developing as a result of my process, but we’re improvising on form, too.

“There is no such thing as free. There has to be order. There’s order in the universe. You can’t escape it. You can’t escape order and there’s no such thing as real freedom. Yes, you get more and more free, but you have to come up with some new laws that allow you to be free, that gives you the authority and power to communicate freedom, or else you’ll just be running around repeating yourself in a little while. Every time you get up you’re not going to have something different to say. We know about habit. If you use these words, these phrases, that’s what you’re going to be using until you find something to free you from that, to give you something else.”

There is the freedom of the individual Threadgill has discovered and encouraged. There is the message he conveys so determinedly in his music that he has created a method of insuring those who play with him partake of it, too. “It’s not necessary for you to do what I do,” Threadgill said. “You’ve got to do what you do, what’s necessary for you to do, and what fits you. But you can learn something from what I do, that can inform you about what you’re doing.” That is the reaction he hopes for from his audience: Not that we’ll immediate like or understand what he’s doing, but that it will free us to do what only we can do.

howardmandel.com

Subscribe by Email |

Subscribe by RSS |