Ornette Coleman (l) at Sonny Rollins’ 80th birthday concert, 2010, at the Beacon, NYC; photographer, please contact this blog post for credit; JazzTimes, no copyright infringement intended

An outpouring of media tributes has followed my hero Ornette Coleman’s death at age 85 on June 11. But many commentators writing of his music — including good ones like Marc Myers in Jazz Wax and Ben Ratliff of the New York Times — have focused mostly on Coleman’s breakthrough recordings from 1958 and ’59, overshadowing music from the last 45 years of his life. This is unfortunate, considering Ornette was an artist of ever-evolving and expanding creativity. So here are ten albums — not in chronological order – offering ready entry to enjoyment of Ornette’s later music. Apologies if they’re hard to come by.

Soapsuds, Soapsuds – Ornette plays tenor not alto in duets with Charlie Haden, and their complementary lines are easy to follow. Some may remember the dryly satiric late ’70s tv soap opera “Mary Hartman, Mary Hartman” — its theme is elevated here.

Science Fiction — Two warmly beautiful vocals by Asha Puthli, the funk-spoof “Rock the Clock” and sturdy Coleman compositions  “Street Woman,” “Civilization Day,” “Law Years” (lawyers?), arranged for larger ensemble but also featuring characteristically inspired, alternatingly beseeching and merry Ornette playing his alto.

“Street Woman,” “Civilization Day,” “Law Years” (lawyers?), arranged for larger ensemble but also featuring characteristically inspired, alternatingly beseeching and merry Ornette playing his alto.

Skies of America — Not much counterpoint in the only available version of Ornette’s  symphony, but his orchestral themes are stated clearly and he blows over/through it all.  Currently on cd paired with Science Fiction in one package.

symphony, but his orchestral themes are stated clearly and he blows over/through it all.  Currently on cd paired with Science Fiction in one package.

Of Human Feelings — OC embraced the electric guitars of rock/soul/pop in the early ’70s, and again ignited negativity from conservative listeners –  even those who’d come to like what he’d done 20 years before. This album is full of short, snappy r&b tunes, OC is right outfront and the grooves are infectious.

even those who’d come to like what he’d done 20 years before. This album is full of short, snappy r&b tunes, OC is right outfront and the grooves are infectious.

In All Languages — Trying to respond to those fans who could dig his acoustic  quartet but didn’t get amplified Prime Time — and vice versa — OC had both ensembles play the same set of catchy songs.

quartet but didn’t get amplified Prime Time — and vice versa — OC had both ensembles play the same set of catchy songs.

Song X — A strong and empathic collaboration initiated by guitarist Pat Metheny, eager to connect to OC, which he does (plus Jack DeJohnette,  drummer-Haden and Ornette’s drumming son Denardo). The ballad “Kathelin Gray” is no-problem listening, which probably can’t be said of the explosive “Endangered Species.”

drummer-Haden and Ornette’s drumming son Denardo). The ballad “Kathelin Gray” is no-problem listening, which probably can’t be said of the explosive “Endangered Species.”

Friends and Neighbors — Best sound quality for Coleman’s quartet with tenor  saxophonist Dewey Redman, Haden and drummer Ed Blackwell having a house party — tricky but memorable lines in “Long Time No See,” plus a community sing-along on the title track.

saxophonist Dewey Redman, Haden and drummer Ed Blackwell having a house party — tricky but memorable lines in “Long Time No See,” plus a community sing-along on the title track.

New Vocabulary — Controversy has been stirred as the Coleman family has sued the musicians who recorded and issued in limited form what now  now stands as Ornette’s last Regardless of the serious issues about whether they had a right to put this out, their setting his nakedly human saxophone sound is 21st century fresh and complimentary. This album may be the best place for listeners currently in their teens or 20s to start listening to Ornette Coleman.

now stands as Ornette’s last Regardless of the serious issues about whether they had a right to put this out, their setting his nakedly human saxophone sound is 21st century fresh and complimentary. This album may be the best place for listeners currently in their teens or 20s to start listening to Ornette Coleman.

Tone Dialing — featuring OC’s later Prime Time cast — includes a harmolodic  interpretation of a Bach prelude and a circa 1995 rap.

interpretation of a Bach prelude and a circa 1995 rap.

Naked Lunch — Film composer Howard Shore created an appropriately creepy score for David Cronenberg’s film of William Burrough’s book (well, not really the book . . .but that’s another story). Ornette performs sparingly, but Shore places his  contributions perfectly, and I’ve always suspected the entire score tracks Ornette’s own structure of Skies of America –Â which was performed by the London Philharmonic Orchestra, same bunch heard here. Well, who knows?

contributions perfectly, and I’ve always suspected the entire score tracks Ornette’s own structure of Skies of America –Â which was performed by the London Philharmonic Orchestra, same bunch heard here. Well, who knows?

Why is Ornette’s later work being overlooked? It’s often the case in every art form that critics get mired in debating initial reactions to work so innovative at the time of its release that it inspires extremely negative reactions from established authorities. Those reactions set the narrative — but later, we ought to be able to toss them off. Roy Eldridge, Charles Mingus, Max Roach and Miles Davis were among those who expressed their dismay at Ornette’s sound and concept. They all held rock solid opinions that for various reasons they weren’t eager to subject to examination of first principles. Perhaps some of them were threatened by what Ornette’s supporters (and his own album titles) proposed in 1958-’60 as revolutionary.

Those first albums, Something Else!!! and Tomorrow Is The Question! (from Contemporary Records), followed by The Shape of Jazz to Come,

Those first albums, Something Else!!! and Tomorrow Is The Question! (from Contemporary Records), followed by The Shape of Jazz to Come, Tomorrow Is the Question Change of the Century and This Is Our Music (’60) on Atlantic, did indeed make a radical break with tired and inhibiting song form and process conventions. They also delivered buoyant and/or wrenching themes and energized, syncopated rhythms, and don’t sound all that weird today.

Those whose listening and critical thinking matured after those innovations were proposed might have accepted all that music with little hesitation — after all, ’60s psychedelic rock like that recorded by Jimi Hendrix, Cream, the Jefferson Airplane and even the Beatles took daring liberties with form and content. They shocked, challenged and entertained vast audiences; their ideas were incorporated into subsequent rock/soul/pop, sometimes watered down but that’s how ideas are assimilated into our culture. This is why it’s safe to say all jazz musicians (and many in other forms, like punk, rap/hip-hop, Western-marketed “world music”) arriving after Ornette were influenced by him, whether they know it or not.

might have accepted all that music with little hesitation — after all, ’60s psychedelic rock like that recorded by Jimi Hendrix, Cream, the Jefferson Airplane and even the Beatles took daring liberties with form and content. They shocked, challenged and entertained vast audiences; their ideas were incorporated into subsequent rock/soul/pop, sometimes watered down but that’s how ideas are assimilated into our culture. This is why it’s safe to say all jazz musicians (and many in other forms, like punk, rap/hip-hop, Western-marketed “world music”) arriving after Ornette were influenced by him, whether they know it or not.

By all means, listen to early Ornette. As a completist, I find Something Else!!! and Tomorrow Is The Question! worthwhile if problematic. On the former, Pianist Walter Norris tried but  didn’t quite get OC’s intentions; on the latter, bassists Percy Heath and Red Mitchell and drummer Shelly Manne clearly aren’t as comfortable with his style as Haden and Blackwell or Billy Higgins are on the Atlantic albums that soon followed.

didn’t quite get OC’s intentions; on the latter, bassists Percy Heath and Red Mitchell and drummer Shelly Manne clearly aren’t as comfortable with his style as Haden and Blackwell or Billy Higgins are on the Atlantic albums that soon followed.

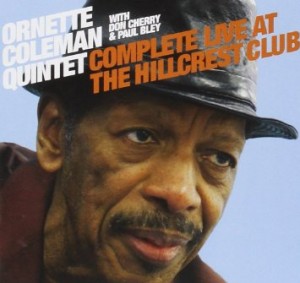

Prior to any of those efforts, pianist Paul Bley had recognized Coleman’s unique gifts, and hired his whole band. Bley eventually issued two loose, live recordings of the West Coast combo with Ornette, Haden and Higgins, now available (probably also unauthorized) as Live at the Hillcrest Club. The performances aren’t polished, but anyone who doubts Ornette could play bebop must hear his version of Charlie Parker’s “Klactoveesedstene.”

That is the first evidence that Ornette Coleman’s sound ideas, drawing on tradition but using all he perceived and could accomplish to free jazz from unnecessary shackles would indeed change the century, leading to much of what we hear now.

<a

[contextly_auto_sidebar id=”04klxWaq4nmTNhWxMrrpUDiXE88tviBG”]