Reviewing a sleeping giant, ESP Disks before its early ’00s revivalÂ

Howard Mandel c 1997, published in issue 157, The Wire

It was a time before psychedelics. Following the seismic cultural disruptions of the mid ’50s, rock ‘n’ roll had hit a period of stasis, enlivened only by the occasional novelty number – the British Invasion had not yet arrived. College kids in the US listened to folk singers and blues of the ’30s from the Mississippi Delta; pop music meant Pat Boone serenading Doris Day over a white-picket fence. There were rumblings of a new soul music but the edge belonged to beatniks, a handful of renegade ‘classical’ composers and some brave men and women of jazz, Then came a promise: “You never heard such sounds in your life.” This promise was made by ESP-Disk.

“I think I can give you a perspective that embraces both the beginning and current status of the label,” says ESP founder Bernard Stollman from his home in New York’s Catskill Mountains, up near Woodstock, about two hours north of Manhattan. “Imagine in 1962 a record label is founded by a somewhat erratic young music lawyer, just starting in the business and also involved in the Esperanto movement. Actually our first production was Ni Kantu En Esperantowhich we described as ‘a sing-along record in the international language,’ and I called the label Esperanto-Disk, but it got shortened.

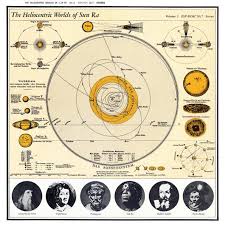

“Then this lawyer got set up,” Stollmam continued, in the third person. “He was living on New York’s upper west side in bachelor digs and had some work representing both Cecil Taylor and Ornette Coleman, and they set him up by holding a three day festival of music at the Cellar Cafe right under his – my – nose. Someone had already told me, ‘You should do something with Albert Ayler, my old school pal from Cleveland who happens to be playing at the Baby Grand club,’ and I’d decided to record him But at the Cellar Cafe I met everybody — Paul Bley, Sun Ra, Steve Lacy — everybody who was anybody on this curious scene. Sun Ra invited me to some loft in Newark, and for some reason I went, wandering around New Jersey late at night in order to hear this big band Sun Ra called his Arkestra. The upshot was in 18 months I recorded 45 productions, totally exhausting my small inheritance which my parents offered to give me if I wanted it before they died.”

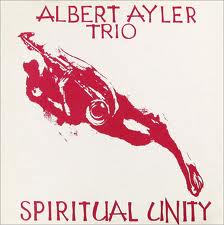

And so the bold manifestations of a vital American musical underground were born. There were other so-called independent jazz record labels active in the same extended, wild decade (roughly 1962-74) as ESP: Prestige, Blue Note and Bob Thiele’s Impulse! that would package some of the most progressive visions of New York new jazz, notably those of Charles Mingus and the incomparable John Coltrane. But those labels’ avant-garde productions were offshoots to their main activities in what could already be called the jazz mainstream, while every ESP release felt like it was out on an unfathomable limb. Artists on ESP didn’t necessarily intend to be iconoclastic or confrontational – they just were. For instance, Albert Ayler, whose first US release, the legendary Spiritual Unity, became the second ESP-Disk.

“I remember the first place I heard Albert Ayler,” recalls Marzette Watts, the multi-reed player, painter, teacher and affable gadabout, currently living in California, whose own ESP disk Marzette Watts, recorded 19 December 1966, featured a company comprising trombonist Clifford Thornton, guitarist Sonny Sharrock, vibist Karl Berger, bassists Junie Booth and Henry Grimes, drummer JC Moses, and fellow saxophonist Byard Lancaster. “Eric Dolphy walked into the Half Note to sit in for Coltrane, who’d taken ill, with this little man in a green leather suit, half-white and half-black goatee. I thought: Who is this little leprechaun? But when he started to play – that sound! To me it was overpowering, but familiar, too. It was familiar from the Holiness church. Albert was simply a sanctified tenor player.”

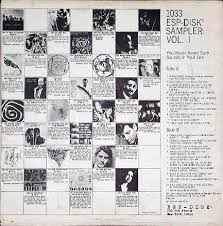

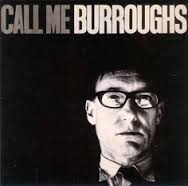

Spiritual Unity looked as distinctive as it sounded, setting a precedent for ESP’s approach to the packaging of this emergent, wild, free music. Most of the early releases came in rough textured, primitively drawn monochrome covers, with not much more information than the players’ strange names – besides Ayler, Pharoah Sanders, Ornette Coleman, Giuseppi Logan, Milford Graves – and the Esperanto legend “Mendu tiun diskon ce via loka diskvendejo au rekte de ESP. Prezo $4.98 Pagu per internacia postmandato.” They were mysterious packages, as irresistibly intriguing as messages in bottles, whether you found them in a dusty bin in a corner in the back of a conventional record store, or unaccountably mixed in among tacky, low-priced pop overruns in giant discount stores in suburban shopping malls. Oddly for those years when homespun independent labels generally released efforts by local artists only within their geographic regions, ESPs seemed likely to wash up anywhere.

the packaging of this emergent, wild, free music. Most of the early releases came in rough textured, primitively drawn monochrome covers, with not much more information than the players’ strange names – besides Ayler, Pharoah Sanders, Ornette Coleman, Giuseppi Logan, Milford Graves – and the Esperanto legend “Mendu tiun diskon ce via loka diskvendejo au rekte de ESP. Prezo $4.98 Pagu per internacia postmandato.” They were mysterious packages, as irresistibly intriguing as messages in bottles, whether you found them in a dusty bin in a corner in the back of a conventional record store, or unaccountably mixed in among tacky, low-priced pop overruns in giant discount stores in suburban shopping malls. Oddly for those years when homespun independent labels generally released efforts by local artists only within their geographic regions, ESPs seemed likely to wash up anywhere.

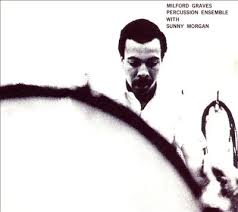

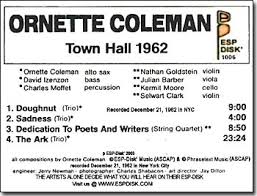

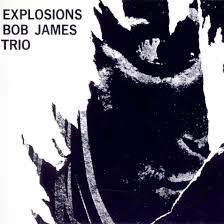

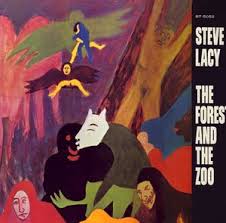

Inside were raw, sprawling, squalling improvisations ostensibly ‘led’ by such little-knowns as Frank Wright, Charles Tyler, Byron Allen, Gunter Hampel, Noah Howard; so-called ‘free jazz’ star Ornette Coleman’s brilliant hybrid of probing  saxophonics, kinetic rhythms and atonal string arrangements recorded in concert at NYC’s Town Hall; The Giuseppi Logan Quartet’s murky, hypnotic emanations, reeking of incense, which introduced the pianist Don Pullen; and the recitation of an angry manifesto, “Black Dada Nihilismus,” by a poet named Leroi Jones, accompanied by Roswell Rudd and John Tchicai in The New York Art Quartet. Pianists Ran Blake, Burton Greene and Bob James (yes, that Bob James) recorded their debuts; Paul Bley cut Barrage with Sun Ra’s alto saxophonist Marshall Allen; soprano saxophonist Steve Lacy brought back The Forest And The Zoo (one LP side for each) with Italian trumpeter Enrico Rava and South African exiles Johnny Dyani and Louis Moholo from a concert in Argentina. There was Ayler’s Bells, 19 minutes long and originally released as a one-sided disk of clear red vinyl, as well as his free for all New York Eye And Ear Control purporting to be a soundtrack for a film by Canadian Michael Snow; Milford Graves’s percussion ensemble with Sunny Morgan (four tracks, all titled “Nothing”); bassist Henry Grimes’s trio with clarinetist Perry Robinson tootling over throbbing darkness; and Diamanda Galas precursor Patty Waters raving for 13 minutes about black being the color of her true love’s hair.

saxophonics, kinetic rhythms and atonal string arrangements recorded in concert at NYC’s Town Hall; The Giuseppi Logan Quartet’s murky, hypnotic emanations, reeking of incense, which introduced the pianist Don Pullen; and the recitation of an angry manifesto, “Black Dada Nihilismus,” by a poet named Leroi Jones, accompanied by Roswell Rudd and John Tchicai in The New York Art Quartet. Pianists Ran Blake, Burton Greene and Bob James (yes, that Bob James) recorded their debuts; Paul Bley cut Barrage with Sun Ra’s alto saxophonist Marshall Allen; soprano saxophonist Steve Lacy brought back The Forest And The Zoo (one LP side for each) with Italian trumpeter Enrico Rava and South African exiles Johnny Dyani and Louis Moholo from a concert in Argentina. There was Ayler’s Bells, 19 minutes long and originally released as a one-sided disk of clear red vinyl, as well as his free for all New York Eye And Ear Control purporting to be a soundtrack for a film by Canadian Michael Snow; Milford Graves’s percussion ensemble with Sunny Morgan (four tracks, all titled “Nothing”); bassist Henry Grimes’s trio with clarinetist Perry Robinson tootling over throbbing darkness; and Diamanda Galas precursor Patty Waters raving for 13 minutes about black being the color of her true love’s hair.

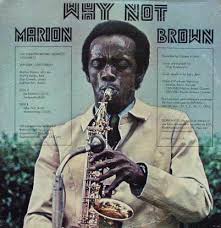

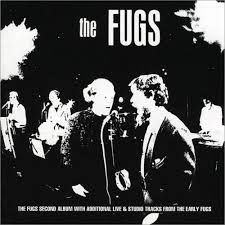

During the course of ESP’s 12 year run, altoist Sonny Simmons blew gritty, gutsy improvisations, Marion Brown brought a delicate lyricism to similarly open, melodic songs, tenorist Gato Barbieri traded lead lines with cellist Calo Scott, bassist Alan Silva introduced a quasi-Asian timbral orientation on Skillfullness, The Revolutionary Ensemble (violinist Leroy Jenkins, bassist Sirone, drummer Jerome Cooper) waxed on about Vietnam, Karel Velebney sent rare missives from the Prague Spring and young tenor hopeful Frank Lowe, fresh from San Francisco and Alice Coltrane’s group, bowed in with Black Beings, taped at Ornette’s Artists House loft space and featuring The Art Ensemble Of Chicago’s Joseph Jarman. Not to mention the flat out East Village folk-poetry of The Fugs (“Monday, nothing/Tuesday, nothing/Wednesday, Thursday, nothing”), the less abrasive Pearls Before Swine, records featuring counterculture icons Charles Manson and Dr Timothy Leary.

from the Prague Spring and young tenor hopeful Frank Lowe, fresh from San Francisco and Alice Coltrane’s group, bowed in with Black Beings, taped at Ornette’s Artists House loft space and featuring The Art Ensemble Of Chicago’s Joseph Jarman. Not to mention the flat out East Village folk-poetry of The Fugs (“Monday, nothing/Tuesday, nothing/Wednesday, Thursday, nothing”), the less abrasive Pearls Before Swine, records featuring counterculture icons Charles Manson and Dr Timothy Leary.

“Yeah, I was kind of central to that ESP activity at the start, I guess you could say that,” Milford Graves agrees, a little reluctantly at first, from his home in Brooklyn. “There was a whole lot of stuff going on then; it didn’t seem like such a big thing.”

Despite his apparent lack of enthusiasm, Graves’s thrilling polyrhythms enriched nearly half of the first 15 or so ESP releases. “I’d always had these special ideas about drumming,” he continues. “Even when I was a kid playing around the neighborhood people said I had a different approach. I was playing in a Latin jazz band, I was hanging out with Cal Tjader and playing with a Mexican sax player named Dick Mesa and [percussionist] Don Alias. We went up to Boston where I met Giuseppi Logan at a jam session he stood up to play and the other musicians said, ‘Oh, here’s that crazy alto player’, and they sat down. But I liked this guy! I thought: I’ll try it. I said to him, ‘What do I do?’ He told me to do what I wanted to. And he liked it.

“Giuseppi Logan was a paranoid schizophrenic, you’d never know what he was going to do. He’d stop in the middle of the street and start screaming about God, and not in a religious way, either. B ut he was always singing those melodies, they were always coming to him, and then he’d look up and say to us, ‘Listen to this! Let’s go find someplace to play!’ I got him his first ESP date, because Bernard wanted to give me a date and I said, ‘No, you ought to record this other musician I know.’ I met Don Pullen through Giuseppi, too: He said to me, ‘You gotta hear this bad piano player.’ Giuseppi also took me to the jam session where I met Roswell Rudd and John Tchicai. I met [Amiri] Baraka [né Leroi Jones] at that same session, and of course he recorded with Ros and Tchicai and me and Lewis Worrell: The New York Art Quartet. We played a gig at the Museum of Modern Art, at the New School for Social Research, at some lofts, but no clubs. And no, we didn’t get any money in ESP, either, but that was just the way things were then. Some of the guys kicked about it; Giuseppi Logan was the most vociferous, almost to the point of violent confrontations. Bernard, he was going to do what he was going to do, though, and he put the music out. He had the courage and insight to hear that music. A few of us got some pennies off him, not much, but it was the idea of it. I don’t really think he was selling so many records, anyway”

ut he was always singing those melodies, they were always coming to him, and then he’d look up and say to us, ‘Listen to this! Let’s go find someplace to play!’ I got him his first ESP date, because Bernard wanted to give me a date and I said, ‘No, you ought to record this other musician I know.’ I met Don Pullen through Giuseppi, too: He said to me, ‘You gotta hear this bad piano player.’ Giuseppi also took me to the jam session where I met Roswell Rudd and John Tchicai. I met [Amiri] Baraka [né Leroi Jones] at that same session, and of course he recorded with Ros and Tchicai and me and Lewis Worrell: The New York Art Quartet. We played a gig at the Museum of Modern Art, at the New School for Social Research, at some lofts, but no clubs. And no, we didn’t get any money in ESP, either, but that was just the way things were then. Some of the guys kicked about it; Giuseppi Logan was the most vociferous, almost to the point of violent confrontations. Bernard, he was going to do what he was going to do, though, and he put the music out. He had the courage and insight to hear that music. A few of us got some pennies off him, not much, but it was the idea of it. I don’t really think he was selling so many records, anyway”

” Bernard said I had to give him Giuseppi’s tapes because he’d signed a contract with him: he was his artist and if I didn’t give him the tapes he’d kick me in the face ”

“My album was one of the last to be released by ESP, I think,” says Frank Lowe sitting in his Manhattan apartment, where he takes life “a day at a time” (12- step recovery program speak). “The label was closing when I came to New York, on its last legs as a record company. But I wanted to be associated with it, just because of Albert and Pharoah and all the musicians who’d been on it.

“My album was one of the last to be released by ESP, I think,” says Frank Lowe sitting in his Manhattan apartment, where he takes life “a day at a time” (12- step recovery program speak). “The label was closing when I came to New York, on its last legs as a record company. But I wanted to be associated with it, just because of Albert and Pharoah and all the musicians who’d been on it.

“I think maybe my friend Rafael Donald Garrett hooked me up with Stollman. Rafael put out one with his wife, Zusann Kali Fasteau, called The Sea Ensemble around that time, too. He was one of my teachers back in San Francisco. He’d taught me ta ji kwan, kind of a martial art based on a breathing technique of focused attention and energy. Or maybe it was Marzette Watts. I think he had an affiliation with Bernard, like served as a sort of go-between for some of the musicians. You should give him a call. I’ve got his number in California.”

“Frank Lowe says I worked for ESP as an A&R man or something?” says Watts when I speak to him later. “Oh, no, no, no, no, no. The first time I ever met Bernard – is he still alive? – had to do with Giuseppi Logan. Is he still alive?

“I remember so well: Giuseppi had just arrived in town with his wife and all his kids, and there was going to b e a big concert for him at Judson Hall, just up the street from Carnegie Hall, though it was a little smaller. Giuseppi was going to play 13 instruments, and he came crying to me that Bernard Stollman told him if he didn’t sign a contract he wouldn’t record him, and how often was he going to get a chance to record playing 13 instruments in front of an audience?

e a big concert for him at Judson Hall, just up the street from Carnegie Hall, though it was a little smaller. Giuseppi was going to play 13 instruments, and he came crying to me that Bernard Stollman told him if he didn’t sign a contract he wouldn’t record him, and how often was he going to get a chance to record playing 13 instruments in front of an audience?

“So I told him, ‘Don’t worry, we’re going to record you.’ I went and got two Neumann mics – I had a friend who worked for ABC Camera Supply, he’d let us borrow mics and recorders and whatever we needed on Friday nights as long as we brought them back undamaged early Monday, for free, no charge. I recorded that concert. But afterwards Bernard came and said I had to give him Giuseppi’s tapes because he’d signed a contract with him: he was his artist and if I didn’t give him the tapes he’d kick me in the face!

“That was the first time I met Stollman. I never worked for ESP, other than putting out my own record on the label and having a lot of tapes I recorded ending up on the label.

“I guess you know the address 27 Cooper Square?” he continues. “That’s where I was living, in the building with Amiri Baraka and that’s where we put on our affairs, starting sometime in ’62 and ending the day Malcolm X was shot. By then times had changed, the scene wasn’t that pleasant any more, there were some things going down that I wasn’ t happy about, didn’t want to have around my loft. When the black audience sat on one side of the room and the white audience sat on the other side, segregated, I didn’t like that, I didn’t want to be associated with it. But that was the loft jazz era, and we were the first of them all.

t happy about, didn’t want to have around my loft. When the black audience sat on one side of the room and the white audience sat on the other side, segregated, I didn’t like that, I didn’t want to be associated with it. But that was the loft jazz era, and we were the first of them all.

“We started having concerts in my big open space before Ornette opened Artists House in SoHo – there was no SoHo then, it wasn’t called that, it wasn’t called anything – and before Sam Rivers’s Studio Rivbea or [Rashied Ali’s] Ladies’ Fort. Everybody played in my loft: Albert and Donald Ayler, of course, Cecil Taylor with Andrew Cyrille and Alan Silva, Bill Dixon, Giuseppi Logan who lived right around the corner near Steve Lacy, Reggie Workman… I think that’s where Stollman discovered a lot of people who recorded for ESP. He was a fan, I guess, and what he heard at our loft whetted his appetite.”

Stollman recalls differently. “I did not come to it as a music enthusiast,” he says. “I was just pissed off that I could not turn on the radio and hear anything I could relate to. I hated blandness and commercialization, and I loved the idea of providing recognition for people who had something to say. I had delusions of grandeur – I thought I could do something about what was on the radio.

“I was a curator, or kind of like an ethnomusicologist, realising there was something happening in music and someone should capture it. So I did. But I was also, basically, a producer who’d run amok. I mean, I was not exact ly out of Harvard Business School. If I’d had ambitions to make it in the music business I would have taken a different tack. If you care about music as a form of sacrament and mystery, the music business is nothing but degrading. It’s as Lillian – or maybe it was Dorothy – Gish said: ‘Art and business do not mix.’ So we came up with the slogan, ‘The artists alone decide what you will hear on their ESP disks.’

ly out of Harvard Business School. If I’d had ambitions to make it in the music business I would have taken a different tack. If you care about music as a form of sacrament and mystery, the music business is nothing but degrading. It’s as Lillian – or maybe it was Dorothy – Gish said: ‘Art and business do not mix.’ So we came up with the slogan, ‘The artists alone decide what you will hear on their ESP disks.’

“We did some things right: I figured out if you didn’t put out ten or 12 albums at a shot, you got lost. I learned that from the Sidney Janis gallery, which had an art show of unknowns named Warhol and Segal and Rauschenberg and put out a big sign saying POP ART, and soon everybody was talking and writing about pop art, whatever that was. So I released ten or 12 discs initially, and it worked like a charm. Guys who did then what you do now sat up and took notice. Within a couple of months someone from JVC in Japan came over and licensed the label for distribution there — for next to no money, but still, something. Then Phonogram came over from Europe, also to license for distribution, and they did a somewhat better job.

“I did nothing as a producer. I might have called a studio once or twice and said, ‘Save some time tomorrow, X-and-so is coming in.’ I paid the bills. I didn’t do anything else. The musicians played as long as they wanted, and typically, 45 minutes later the engineer would cut up the tracks and there’d be a production No second takes.”

None were necessary, as the ESP crowd valued spontaneity over virtually everything else. Many of the best albums were recorded live, like Ayler’s Prophecy (with poet Paul Haines serving as tape-operator) and Sun Ra’s Nothing Is… (with a cover photo depicting Ra’s head engulfed by fire) which contained tapes of his ‘band from Outer Space’ from a 1966 tour of New York State colleges. The studio sessions were similarly conceived; once asked by a Danish journalist how he maintained his cosmic energies in a studio, Ra replied that in the case of his ESP discs he’d been lucky enough to have an audience in engineer Richard Alderson, “who happened to like and truly understand the music.”

None were necessary, as the ESP crowd valued spontaneity over virtually everything else. Many of the best albums were recorded live, like Ayler’s Prophecy (with poet Paul Haines serving as tape-operator) and Sun Ra’s Nothing Is… (with a cover photo depicting Ra’s head engulfed by fire) which contained tapes of his ‘band from Outer Space’ from a 1966 tour of New York State colleges. The studio sessions were similarly conceived; once asked by a Danish journalist how he maintained his cosmic energies in a studio, Ra replied that in the case of his ESP discs he’d been lucky enough to have an audience in engineer Richard Alderson, “who happened to like and truly understand the music.”

The circumstances surrounding the recording of perhaps ESP’s most famous live release, Ornette Coleman’s 1962 Town Hall Concert, hint at the harsh climate in which many of the musicians associated with the label were forced to operate.

“My intention always was to be recognized for my work as a composer as much as a saxophonist, a performer,” Coleman told me in the late 1990s – by then having succeeded in the effort. In 1961, the year before he recorded Town Hall Concert he had ended his extraordinarily productive two-year association with Atlantic Records. His music had become increasingly experimental, even considering where he’d started, with his final Atlantic sessions comprising unique chamber ensemble pieces with the conservatory-sanctioned ‘Third Stream’ composer Gunther Schuller. “Bu t I was getting a bad relationship with critics and the musicians,” he continues, “because I wasn’t playing the standard jazz, and they didn’t want to support me. Club owners didn’t want to pay me and stuff like that and I didn’t want to get paranoid and evil or something so I said, ‘Well, maybe everybody just don’t understand what I’m trying to do as a player, so I’ll retreat and just start writing music.’

t I was getting a bad relationship with critics and the musicians,” he continues, “because I wasn’t playing the standard jazz, and they didn’t want to support me. Club owners didn’t want to pay me and stuff like that and I didn’t want to get paranoid and evil or something so I said, ‘Well, maybe everybody just don’t understand what I’m trying to do as a player, so I’ll retreat and just start writing music.’

“I started writing Skies Of America at that time, and my first string quartet – I performed it in ’62 so I must have been writing it in ’61. This is a true story: I took all my life savings and I hired a string quartet and I got the guys together from my group – David Izenson and Charlie Moffett and myself – and I went and rented Town Hall.” Word is that Ornette’s accountant, the late Irving Stone – after whom John Zorn’s East Village recital room is named – also invested in this concert.

“I’ll never forget,” Ornette continued. “It was 21 December. That night there was a subway strike, a newspaper strike, a taxi strike, everything was on strike, even a match strike. Not only that, I hired a guy named Jerry Newman to record it for me and he committed suicide. Oh, I could tell you lots of tragedies that happened. But that recording was Town Hall.”

It was the sixth ESP release, and clearly sounded the call of independence: from rigid musical classi fications and segregations, from traditional assumptions and pretentions, from a jazz past that hewed to the imperatives of the entertainment industry towards an artist-controlled (if, possibly, artist-self-financed) future.

fications and segregations, from traditional assumptions and pretentions, from a jazz past that hewed to the imperatives of the entertainment industry towards an artist-controlled (if, possibly, artist-self-financed) future.

“I think Bernard had ears for what we were doing, I think he just liked it, is all,” Milford Graves says. “He never told us to do anything that he wanted. I think he had some soul, he had that style, that he liked it. I remember he’d be there in the back of a session where we were playing, smiling and grooving. He was not cold! I’d never say that about him. Though I remember going to sessions, too, where he didn’t say nothing.”

Stollman says he followed no recognized models for building a label. “I’d say to somebody, ‘I think you should have an album.’ I wouldn’t know the size of the group, often. But the musicians were all part of a network, they knew each other and worked with each other, so I wasn’t too concerned. If they liked what they did, it was fine by me.

“Bob James, for instance, was a recent graduate of University of Indiana, I think he handed me a ta pe and I said, ‘OK’. He gave me a cover he’d shot in Australia, part of a poster or something. We didn’t have much conversation about it. I couldn’t even tell you why I said yes. It was intuitive. It was serendipitous. It shouldn’t have worked, but it did.”

pe and I said, ‘OK’. He gave me a cover he’d shot in Australia, part of a poster or something. We didn’t have much conversation about it. I couldn’t even tell you why I said yes. It was intuitive. It was serendipitous. It shouldn’t have worked, but it did.”

The tape James handed Stollman would become one of ESP’s most notorious and baffling releases: Explosions, a unique fusion of free jazz, cocktail lounge piano and musique concrete, a part-collaboration with composer Robert Ashley, that is so far removed from James’s subsequent fusion output (including the rap/breakbeat staple “Take Me To The Mardi Gras”) as to occupy another universe entirely.

“The label had a life of its own, still does today,” continues Stollman. “It was and is an organic creature. And I didn’t know what I was getting. I certainly didn’t know that little kid I was recording was someone like Amiri Baraka.

“But then I wasn’t satisfied documenting what was happening in jazz, I had to take on the US government, too. I felt Vietnam was an atrocity. I was horrified, as a whole generation was, and felt that something should be done. It was a media age, so something should be done in the media. The Fugs and Pearls Before Swine felt the same way, and they were able to express it pretty bluntly, and I was able to put their music out.

“That led to ESP having some very subtle government problems. They planted someone in our office. They audited our taxes, punitively. They bugged our phones, intimidated our distributors. At that time there were no federal anti-bootlegging statutes on the books, and our pressing plants went to work on The Fugs and Pearls Before Swine albums, pressing them on their own and selling directly to our distributors. That’s why Ed Sanders was convinced we’d robbed The Fugs blind. Our distribution may have been marvelous but we never saw any money from those sales.”

“That led to ESP having some very subtle government problems. They planted someone in our office. They audited our taxes, punitively. They bugged our phones, intimidated our distributors. At that time there were no federal anti-bootlegging statutes on the books, and our pressing plants went to work on The Fugs and Pearls Before Swine albums, pressing them on their own and selling directly to our distributors. That’s why Ed Sanders was convinced we’d robbed The Fugs blind. Our distribution may have been marvelous but we never saw any money from those sales.”

Ed Sanders’s charges weren’t the first time Stollman had been accused by artists (or more likely, their suspicious, protective fans) of malfeasance, nor would it be the last.

“I understood the record business,” Marzette Watts says, “and I knew I’d never get a dime for my ESP record. That was OK, because I worked for five years off of that record. I knew Bernard had great distribution – he had a flair for that merchandising thing. I recorded in December and by June I was working in Moscow, and I saw those ESP records there and in London and all over Germany, Scandinavia, Switzerland and Northern Europe.

“Now, Patty Waters lives out here, and I ran into her recently, after not having seen her for 20 years, and the first thing she said to me was, ‘I still haven’t gotten my ESP session pay. Did you get yours?’ She always thought we all got rich except for her off those records. Well, she should have! If you listen, she’s really into some stuff there. I hear her doing things Betty Carter does now, free associative things Patty was doing that in the ’60s.

“You know, one of the things that kept someone like Symphony Sid from putting us on the radio was that they couldn’t deal with the music we were playing, but part of it also was that we were the first generation of black jazz musicians to have degrees, to be educated, to have the ability to write our own liner notes, if we wanted them. Bernard was not afraid of innovation. You could say he was a modern Medici, but he was really performing a great service and taking a big chance, lots of chances.

“You know, one of the things that kept someone like Symphony Sid from putting us on the radio was that they couldn’t deal with the music we were playing, but part of it also was that we were the first generation of black jazz musicians to have degrees, to be educated, to have the ability to write our own liner notes, if we wanted them. Bernard was not afraid of innovation. You could say he was a modern Medici, but he was really performing a great service and taking a big chance, lots of chances.

“If you’re an artist, you’re promised the talent, not the money. I get a little bit of a sour taste in my mouth thinking about certain aspects of the history of jazz, when someone who’s a copy cat takes credit for the innovation. But America does that to everybody. It’s a distortion of the truth. But I didn’t expect it to be any other way. I came from an art background. I knew art history. I knew painters died, innovation was overlooked, that there is never any money for the artists. Money isn’t why you do art – you do it because you have to.

“Bernard never send me a royalty check, but I don’t think I ever asked him for a royalty check, either. I don’t put horns on him. Do some of the other guys?”

“Yeah, there was some talk about him at that time, in the ’60s, ’70s,” Frank Lowe reports. ”’Motherfucker is ripping off Bud Powell, and Billie Holiday’s estate.’ That was under the surface, that talk. But I said to myself, ‘Wh o am I? I just got here, I’m a newcomer, I can’t lose anything. If I have to pay some dues, so be it.”’

o am I? I just got here, I’m a newcomer, I can’t lose anything. If I have to pay some dues, so be it.”’

“In the ’60s I worked briefly with the attorney who was handling the estates of Charlie Parker and Billie Holiday,” Stollman explains. “I did some work on those estates, for Louis McKay, who was Billie’s executor, and Leon Parker, executor for Bird, and then I was cleared by the estates to release the material by them. I was also Bud Powell’s attorney for the last two years of his life, but releasing those albums was a huge mistake. Despite our assertions, we were said to be putting out bootlegs. And we were not a classic jazz label in any case.

“I know there was speculation I was a rip-off, enriching myself at the musicians’ expense,” he admits, “which was probably also my own fault, because I ran the company in such a slipshod way. I was irresponsible. The musicians were entitled to royalty statements, even if they didn’t earn any royalties, as a matter of respect. So I deserved the static I got. But there’s no one living today who will say I interfered with the creation of their music. From that standpoint, I can be proud of what I did.”

Stollman’s pride is further vindicated by the interest being shown in ESP by the Smithsonian Institution, the official US archives which he says has negotiated to release ESP catalogue titles in the States under a Smithsonian-E SP imprint, and initiate 45 new productions this coming summer [[As of April 2015, this has never happened]]. Stollman himself is no longer involved in the label; after closing shop in 1974 he concentrated on his legal career, serving as assistant attorney general for the state of New York from 1978 until his retirement in 1991. Responsibility for new ESP music rests with his wife, Flavia Stollman, and her associate producer, Woodstock-based Jayna Nelson. [This too changed; sometime around 2000, Bernard Stollman reasserted his direction of the label].

SP imprint, and initiate 45 new productions this coming summer [[As of April 2015, this has never happened]]. Stollman himself is no longer involved in the label; after closing shop in 1974 he concentrated on his legal career, serving as assistant attorney general for the state of New York from 1978 until his retirement in 1991. Responsibility for new ESP music rests with his wife, Flavia Stollman, and her associate producer, Woodstock-based Jayna Nelson. [This too changed; sometime around 2000, Bernard Stollman reasserted his direction of the label].

As for the stars of the old ESP, “Some of the senior musicians want to join in the Smithsonian project just for the prestige of it,” Stollman claims.

Most of them are not readily available. Ayler, of course, was found floating in New York City’s East River, stabbed to death, in 1970. Sun Ra is no longer on this plane, nor are Charles Tyler, Don Cherry, Frank Wright, Rafael Garrett or Don Pullen. Marion Brown is in a nursing home in Brooklyn suffering from some degree of Alzheimer’s disease [he died in 2010]. Henry Grimes, according to Marzette Watts, had a family history of mental problems and has been way off the scene for more than a decade; his former friends presume he’s dead [Grimes was found to be living in Los Angeles, and returned to an active performing career in 2002]. And Giuseppi Logan? “I last saw him more than ten years ago, he was on 57th Street looking very down, grey and derelict,” Milford Graves says sadly. “I don’t know what’s beco me of him, I couldn’t say.” [Logan also resurfaced, reportedly after having been institutionalized for many years in a southern state, cited playing in a park in the East Village in 2008.]

me of him, I couldn’t say.” [Logan also resurfaced, reportedly after having been institutionalized for many years in a southern state, cited playing in a park in the East Village in 2008.]

Others of the old ESP crowd have moved on to better things. Sunny Murray, who played on Ayler’s Spiritual Unity, is somewhere in Europe, as are Burton Greene and Alan Silva. Sonny Simmons at this writing is in Paris and releasing new music on the New York label CIMP, and Steve Lacy has apparently quit that city, having established himself securely as an improvising master [Lacy died in 2004]. Ornette’s Harmolodic label is an active subsidiary of Verve/Polygram, and Coleman hosted a fabulous Christmas ’96 party, complete with a raucous jam session and Frank Lowe blowing in the frontline.

Paul Bley records voluminously, and Pharaoh Sanders is enjoying a resurgence of interest thanks in part to his association with Bill Laswell and the Axiom label. Gato Barbieri has returned to performing; John Tchicai is playing from his base in California [d. 2012]; Roswell Rudd lives in upstate New York; Amiri Baraka holds a university post in New Jersey [d. 2014]. Professor Milford Graves teaches holistic arts from his studio in Brooklyn; his performances are all too infrequent, considering the spiritual power of his drums.

“You know, the history of this music is told in terms of all the great musicians,” says Graves, “but you got to remember there were the guys who didn’t go out, for one reason or another, who sat at home with their instruments, and could have still been great. Me, I looked ahead back then and I didn’t think anything too much would be happening for me until the year 2000; now there’s only three years left.”

there were the guys who didn’t go out, for one reason or another, who sat at home with their instruments, and could have still been great. Me, I looked ahead back then and I didn’t think anything too much would be happening for me until the year 2000; now there’s only three years left.”

“Those ESP records had a huge impact,” Frank Lowe maintains. “I was flattered to be part of that caste. After all, the first record I was influenced by, growing up, was Pharoah’s First [the third ESP-Disk], then some of Ayler’s. I’d had my ear to the speakers listening to Coltrane, and ESP had this record by Marion Brown, who’d been on Trane’s Ascension, called Why Not? where he’s wearing a light beige trench coat on the cover. It was almost as good as Three For Shepp on Impulse!. And The New York Art Quartet, I was influenced by them. That’s where I first saw Milford Graves. I played in his band for a couple of years, too.

Black Beings was a hardcore record. ESP was a hardcore label, too. And it’s a good thing it existed, because it’s almost like the music didn’t exist, if not for that documentation. You could damn near rewrite history and just purge it of all that music, as some critics have tried, if it wasn’t for those ESP albums.”

[contextly_auto_sidebar id=”4EmEKDCXyx7E48we1L46PnZKdA0fW730″]