Composer-reedist Henry Threadgill created a stunning tribute at WinterJazz Fest 10 in New York City last night to honor his great friend Lawrence Douglas “Butch” Morris, who died just short of his 66th birthday on January 29, 2013. The nearly hour-long piece had two movements — a long, complex, multi-layered improvisation based on Threadgill’s score of shifting intervallic cells, and after a brief pause, a wrenching, Â climactically exultant tutti that distilled his characteristically angular and disjointed yet coherently emphatic expressivity, and over powerful drumming reached to the sky.

Henry didn’t play, he conducted — but made no attempt at Conduction, the revolutionary alphabet of hand gestures Butch invented and codified to enable ensembles of any instrumentation to engage in meaningfully directed spontaneous composition. Instead, he waved members of his “Ensemble Double-Up” — pianists Jason Moran and David Virelles, alto saxophonists Curtis Macdonald and Roman Filiu, cellist Christopher Hoffman and tuba player Jose Davila (both of Threadgill’s ongoing band Zooid), and traps drummer Craig Weinrib — to the fore of a mass of sonic detail, which was unfortunately muddy in the large, open, chairless hall of Judson Church, long a center of artistic experimentation and righteous political activity.

Threadgill’s music — from ensembles including his early trio Air, seven-person Sextett, electrified Very Very Circus, Â Society Situation Dance Band, lyrical Make A Move and dynamic Zooid — has seldom been easy (as if that’s a desirable attribute). The man himself bubbles with energy, edgy humor, a questing nature and occasional fits of pique, all attributes evident in his imaginative enterprises. Ensemble Double-Up’s members worked heroically to realize his vision, which in the remembrance’s first episode teemed with life akin to an urban milieu: richly individualized voices in fast-flowing contrast, at cross-purposes and arriving at occasional fleeting harmonies.

Weinrib, behind baffles, slashed at his cymbals and struck unrestful polyrhythms. Davila pumped a deep bottom in tandem with Hoffman, most often plucking pointed accents. The saxists both managed to blow in the unique vein Threadgill has discovered for himself, Maconald somewhat plaintively and Filiu rather more bluntly. Virelles and Moran, among the most accomplished of exploratory jazz pianists under 40, played clusters, runs, dissonant chords, and suffered most from the room’s acoustics; I longed for more body and tone overall.

Threadgill’s ouevre has never been simply about melody or changes. Instead, it is intended as to convey the adventure of diving into the unknown and unexpected. That’s something Butch Morris responded to strongly in his compadre’s efforts, and something he himself was interested in, though he tended to take a different, less determinedly bristling approach, which Threadgill, now 69, deeply appreciated.

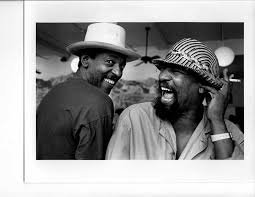

The two had much in common and in complement. Both came to musical maturity in community-oriented, musician-run collectives, Butch in Watts with Horace Tapscott’s Pan Afrikan Peoples Arkestra and bassist Charles Moffett’s rehearsal big band, Henry with Chicago’s Association for the Advancement of photo credit sought, no copyright infringement intendedCreative Musicians (AACM). They were both Viet Nam veterans — and joined forces with  fellow vets under the leadership of violinist Billy Bang on the album Vietnam: The Aftermath. They first recorded together in David Murray’s 1980s octet, which included such  like-minded improvisers as trumpeter Olu Dara, trombonists Craig Harris and George Lewis, bassists Fred Hopkins and Butch’s brother Wilbur, drummers Steve McCall and Edward Blackwell, pianists Don Pullen and Anthony Davis. Both were sociable, yet cherished privacy and could be verbally elusive as well as witty. On a personal level, they simply clicked. The two lived much of the time within a few blocks of each other in the East Village, shared a lot discussion of musical ideas, late night hang outs and laughs.

Indeed, to know Butch Morris, as cordial and charming as he was original and astute, was to laugh with him, delve into broad ranging discussions, and love him. Many attendees at this concert were players, dancers, writers and aficionados personally touched by Butch, who likely had collaborated with him. Some wept openly, and at the end everyone cheered the uncompromised intensity of feeling Henry Threadgill evoked, throwing his arms into the air, Â commanding his musicians’ focus to simultaneously mourn and celebrate a man whose memory sustains artistic ambitions, and whose legacy of Conduction, songs and his tender cornet playing should not be forgotten. Threadgill’s remembrance of Morris was so resolute and moving that I found myself unable to listen to any more of the couple of dozen exemplary bands performing in multiple venues as WinterJazz Fest 10 continued to 3 a.m. Better to walk through bustling Greenwich Village, breath the misty air and, as brought to the purpose by Henry Threadgill, recall.