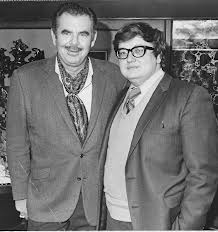

I’m as sad as any Chicago-born & raised movie fan about the death of Roger Ebert, who I saw regularly in the Chicago Sun Times/Chicago Daily News offices when I was a copyboy there in the ’70s, but to whom I never spoke. And I take umbrage at the characterization of him as a “middle-brow” — because Ebert was not that, rather the best kind of populist critic, as the New York Times obituary suggests.

“A critic for the common man” is the Times headline. “His opinions propelled film criticism into the mainstream of American culture,” writes Douglas Martin. “Not only did he advise moviegoers about what to see, but also how to think about what they saw.”

That’s correct: Ebert did go mainstream as no movie critic had before him in such a big, smart way. If he did not deliver the aperçus of Kael, Sarris, Ferguson and Farber, perhaps it was because he was doing the Chicago thing of writing plainly, swiftly and without pretentions. This is a skill lost on critics who are from their outset pretentious.

Ebert’s thinking was not “middlebrow,” however, nor were his instincts and taste. He loved movies, the very movie-ness of them, but was much more than an “earnest enthusiast,” as Terry Teachout has described him. The Chicago Daily News nightlife/jazz/theater/movie critic/feature writer Sam Lesner, back in the day, was an earnest enthusiast — honest but with little genuine insight, flying opinions from the seat of his pants. Chicago Tribune theater critic Claudia Cassidy at the time was, by contrast, an outright elitist; knowledgable, yes, but self-absorbed, wielding her influence despotically. Ebert vis á vis his writing seemed like a regular guy, on the level with metropolitan daily newspaper readers. All the better to reach them with his on-target responses to an art form meant for everybody.

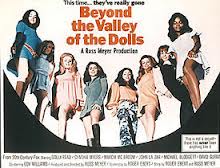

Ebert was far from unsophisticated, though and could analyze Bergman, Fellini, Antonioni and Godard with comprehension equal to anyone’s. He also had a finely honed sense of irony and — more rare yet — the guts to put it to the test, writing Beyond the Valley of the Dolls, one of the first intentionally trashy, highly referential movies intended to be enjoyed for its surface luridness as well as its sub-themes, in the way Quentin Tarantino has brought to an art.

Ebert, even in collaboration with director Russ Meyers, was no Tarantino. Maybe he would have been if he’d grown up in L.A. and video stores had been available to lounge about in for minimum wage. Instead he grew up amid the cornfields surrounding University of Illinois (Champaign/Urbana) and as a kid worked on a grade school newspaper, edited his high school newspaper, and according to the Times at age 15 earned “75 cents an hour covering high school sports for The News-Gazzette in Champaign.” Originally hired by the Sun-Times as a feature writer, he became the paper’s movie critic at age 24. I bet he felt like he’d landed on one comfy throne.

His movie reviews were always crisp and clear. He liked being entertained, but abjured unearned or false sentimentality. He was into action, adventure, comedy, lighthearted musicals and gripping drama. Violence didn’t bother him unless it was transparently pornographic, a point he made clear in his screenplay for Beyond the Valley of the Dolls, which spoofs everything including itself.

I haven’t watched that flick in many a year, and don’t recommend it for intellectual study or even dorm-room debate, such as Django Unchained, Pulp Fiction and Reservoir Dogs can stand up to. But I admire Roger Ebert for having conceived a movie that was knowingly trashy — what we called “camp” — and seeing it produced, distributed, reviewed (often scathingly), then returning to his desk at the Sun Times to resume writing about other movies. That in itself demonstrated to me the gumption he so heroically showed in fighting to be himself every inch of the way as his illness progressed. I never spoke to Ebert, but he spoke to me. And what he said was as meaningful as anything written by others in more high falutin’ prose or precious style.

P.S. — Roger Ebert died on the 100th birthday of Muddy Waters, another Chicagoan (born and raised, though, in the Mississippi Delta) who plied his art in a straightforward, hard-hitting way. The debt of contemporary pop music to people like Muddy remains unpaid, acknowledged among the cognoscenti but no longer assumed by casual listeners. Too bad for us: Muddy and his peers laid down the bedrock upon which Elvis, the Stones, the Beatles and subsequent American rock built. Same as Ebert, who modeled how most people today think and talk about the movies. Both thumbs up to them both.