The second weekend of January is now the fullest on NYC’s jazz calendar, with continuation of the high energy, two-night showcase Winter Jazzfest in multiple Greenwich Village venues, and aspirational ensembles elsewhere playing (they hope) for booking agents and curators attending the annual Association of Performing Arts Presenters convention. Having responsibilities of my own Friday and Saturday after the Jazz Connect conference (held in conjunction with APAP), I had to limit my actual listening — but took in the start of pianist Monty Alexander’s Harlem-Kingston Express plus tenor saxophonist Marcus Strickland’s Twi-Life, the Revive Big Band, singer Claudia Acuña and solo saxophonist Colin Stetson as well as vocalist Macy Gray with saxman David Murray’s Big Band at Iridium in midtown.

Ms. Gray has a wild look and a crazee voice — like a little girl’s with bluesy strain — which she used to holler out brief phrases such as “Are you a psychopath” and “I’ve got a monster lover,” nuancing emphasis to lend her words multiple dimensions. This repertoire can get repetitious, so Murray has written backup arrangements for maximum variety and blazing solos. On this gig his aggregation included Marc Cary, a veteran of D.C.’s go-go scene who supplied carnivalesque comping on piano and organ; drummer Nasheet Waits, who after the second set Friday night raced down to the Village to lead his own quartet at Winter Jazzfest, and regulars such as baritone saxophonist Alex Harding and Mingus Murray on guitar, leading into and/or emerging from richly harmonized, expertly executed, rhythmically sweeping charts. “Can I take this to Las Vegas?” Murray joshed with me after a second set Saturday night. Why not? And why aren’t more neo-soul divas taking the plunge to employ real live blowers? Murray’s men added bang to her buck.

Colin Stetson is well-known amongst indie rockers for his tours with Arcade Fire, but jazz devotees may know his striking musicality drawing on extended techniques for bass and alto saxes mostly from online videos. Stetson is a master at circular breathing, which as I understand

it allows the production in his horns of a standing sound wave. This kind of air column lets the skilled manipulator (besides Stetson, hear Evan Parker, Roscoe Mitchell or the late Rahsaan Roland Kirk) to create long, unbroken phrases and highly audible harmonics — that is, pitches that arise from the specific notes being fingered. We hear both the notes and their harmonics. Then Stetson adds a vocalization, humming or “singing” while he blows. The keypads of his saxes have percussive qualities as he rapidly presses them and his horns are well-amplified, so  three or four strains of sound are produced simultaneously.

This is impressive, but of course the real issue is what a musician does with the sounds. Stetson works them over to create coherent, pre-determined song-like structures. I kept wondering what he’d play if interacting with a rhythm section or another melody instrument. I’ll find out — he has recently recorded with fellow fire-breathing saxophonist Mats Gustaffson.

Ms. Acuña, who preceded Stetson at the Bitter End — best known as a folkie hangout — is a beguiling Chilean-born- and-raised vocalist and songwriter. She sings mostly in Spanish, which I don’t speak, but her voice is warm, her delivery is artful and confident, her stage manner casually dramatic and very inviting. Accompanied by a tight keyboard-electric bass-electric guitar-drums group, she was a pleasure to hear. At the apex of her show she segued into “You Are My Sunshine” (in English), expressing both that lyric’s simplicity and its nobility. I was glad of that.

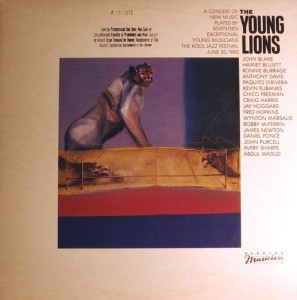

The crowd at the Bitter End was mostly seated — not so at Sullivan Hall, where the Revive Big Band disproved those ignoramusi who pose jazz as dead, or as good as so to newer urban audiences. The RBB, led by trumpeter Igmar Thomas, is in fact an outgrowth of the Revive Music Group (formerly Revive Da Live), a vibrant, young and funk-embracing community that presents concerts and club shows (including a regular jam session at NYC’s Zinc Bar). Brainchild of Mehgan Stabile, the Revive Music Group comprises at least a couple of dozen rip-roaring players whose vocabularies are build on jazz models but don’t end in 1966 (or 1982, when Bruce Lundvall produced a record titled  The Young Lions documenting a Kool Jazz Fest concert featuring Wynton Marsalis, among others; the term would subsequently be associated with Marsalis’s neo-bop directions). Most of the Revive-associated players seem to be in their late 20s/early 30s, as were the standees in the packed house, throbbing with social buzz, eager to enjoy rakish brass and racing reeds over hard swing with pronounced backbeats. Marcus Strickland was in the band’s front line; he’s a full-bore tenorist who had featured the veteran powerhouse trombonist Frank Lacy in his own small group set, just prior to the RBB. Revive was behind the whole night at Sullivan Hall, and most of the folks in that club looked like they intended to say to hear harpist Brandee Younger’s tribute to the late Dorothy Ashby, trombonist Corey King,

The Young Lions documenting a Kool Jazz Fest concert featuring Wynton Marsalis, among others; the term would subsequently be associated with Marsalis’s neo-bop directions). Most of the Revive-associated players seem to be in their late 20s/early 30s, as were the standees in the packed house, throbbing with social buzz, eager to enjoy rakish brass and racing reeds over hard swing with pronounced backbeats. Marcus Strickland was in the band’s front line; he’s a full-bore tenorist who had featured the veteran powerhouse trombonist Frank Lacy in his own small group set, just prior to the RBB. Revive was behind the whole night at Sullivan Hall, and most of the folks in that club looked like they intended to say to hear harpist Brandee Younger’s tribute to the late Dorothy Ashby, trombonist Corey King,

keyboardist-producer Mark de Clive-Lowe’s CHURCH, and others I’ve never known about but now will check out.

Pianist Monty Alexander, who opened the first night of the Winter Jazzfest at le Poisson Rouge by dedicating his set to Claude Nobs, founder of the Montreux Jazz Festival who had just died as the result of a ski accident, is a well established  artist.  And so he could deal with the hordes of people sitting on the floor before the stage, bunched at the bar and leaning up against the rear walls of a room that, as the basement of the Village Gate, used to house a weekly Jazz Meets Latin night. Alexander’s “Latin” (read: Afro-Caribbean) tinge is less Hispanic than Jamaican. Having recorded the Bob Marley songbook and a collaboration with reggae-famed guitarist Ernest Ranglin, among other projects, he indisputably grooves. I could only stay in lpr to listen to him for a minute, but I felt the fervor. And that, besides the showcasing of 70+ bands that are bursting to break beyond New York’s jazz spheres, is what Winterjazz Fest — this year was the seventh — is all about.