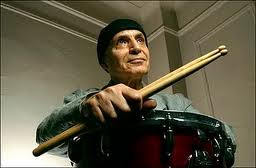

Drummer Paul Motian died November 22 at age 80. He was a unique sound organizer and constant actor on the jazz scene in New York City for nearly 60 years. He spoke to me for Down Beat in 1986 — an interview I offer in slightly different form below. Of course it doesn’t account for 15 more years of music, much of which has been stellar. But Motian’s voice — onrushing, exacting, broken occasionally by his barking laugh, may come through:

Drummer Paul Motian, like many a jazz player, lives in the eternal present. “When there were bohemians, I was a bohemian; when there were beatniks, I was a beatnik; when you were a hippie, I was a hippie, when you were a yippie, I was a yippie! I’ve been through the whole thing and even before there were bohemians, there was something else – I don’t know what it was – and I was that.”

He laughs dryly but enthusiastically, comfortable in his upper West Side of Manhattan apartment, hoping perhaps that his yuppie days are coming so he can decide whether or not to buy his soon-to-be-condo rooms with a view. The piano Keith Jarrett grew up on fills Motian’s living space, along with a partially setup drum kit, some stereo equipment he’s unhappy with, severeal healthy plants, records, shee music and well worn, friendly furniture. One acquires things, even living in the moment. Maybe what’s surprising to Motian, now that he thinks about it, is the extent of his past.

It’s been an amazingly brief but music-filled three decades since Motian made his first record – “with a band made up of Bob Dorough, the piano player, a bass player named Al Cotton, trumpeter Warren Fitzgerald, Hal Stein, a sax player, and Bob, uh, Newman, I think tenor player, in the summer of ’55, for Progressive Records, in New York and New Jersey” – not long after his Navy discharge. Could it have been so long ago he met the pianist Bill Evans, worked behind clarinetists Tony Scott and Jerry Wald, traveled with Oscar Pettiford’s big band, drummed with everybody at Birdland, at Small’s Paradise and the Café Bohemia, formed the trio with Evans and Scott Lafaro, joined the Jazz Composers Guild’s October Revolution, played in groups led by Arlo Guthrie, Charles Lloyd, Paul Bley and Keith Jarrett, sparked Charlie Haden’s Liberation Music Orchestra and Carla Bley’s Escalator Over The Hill, began composing and recording, first for ECM and for Soul Note, too, under his own name, fronting his own combos, all the while maintaining his own highly poetic sound? Can’t be: check how open, alert and at the breaking point his most recent albums are. (It Should’ve Happened A Long Time Ago with guitarist Bill Frisell and tenorist Joe Lovano, Jack of Clubs with saxist Jim Pepper and bassist Ed Schuller added to make five. Taste and momentum have long been Motian’s long suits: his love of music and the beat – “I was talking to Dewey Redman,” he mentions, “and he said it’s like a blessing and a curse at the same time” – goes back to his childhood.

“I was born in Philadelphia and grew up in Providence, Rhode Island; my parents moved there when I was one or two years old.” Both his folks were Armenians born in Turkey. His father was much older than his mother, and had been hired by her father to travel to Havana – where she’d gone from the Middle East – to marry, bring her to the States, then have the union annulled. Instead, the marriage took.

Besides his swarthiness, Motian retains his ancestry by calling his publishing company Yazgol Music, after his grandmother. “They spoke Armenian and Turkish at home, but the language I know is a mixture of both. I can only spak it with people from the same province as my parents.

“I heard Armenian music, Arabic music, Egyptian, Turkish, all on 78s on a wind-up phonograph when I was a kid. I like the Turkish stuff; it seems to be more earthy, have more bottom. But what got me started playing . . .?

“Actually,” he shrugs, “I started on guitar, but it didn’t go. I signed up on the street with a cat recruiting kids to take lessons. I was attracted because I like cowboy movies – the guy puts his guitar around his neck, strums, sings – that looks like fun, I thought. I want to do that. But when I went to the class, here were 10 or 15 kids with guitars across their laps – Hawaiian guitars, right? I was real disappointed. I split, took the guitar home, put a rope around it, put it around my neck, took the metal bridge off it, and just started strumming. That was the end of that.

“The drum thing started because there was a drummer in the neighborhood and I used to hand out with his brother, who was my age. This drummer was a little older, like 20, and when he played people used to gather in the street on his stoop to listen. I got into that. I used to go over there a lot, and I liked what I heard. I really liked it, and before you knew it I was taking lessons with this guy. I was about 12. Then I found a more legitimate teacher, then another one, and just grew from that.

“I played in the school band, starting around seventh grade, and in high school played in the marching band. Also, they had a dance band and I got into that – two or three trumpets, a couple of trombones. I got out of high school in ’49, started gigging around Providence in parts, playin’ tunes. I got involved with a band that toured New England, playing stock arrangements, Glenn Miller stuff, and Dorseyes, yeah; and they used to have big bands come to theaters in those days. I caught Count Basie and Duke Ellington and Jimmie Lunceford, Gene Krupa – I used to go backstage for autographs.

These were the days of critical disputes over the merits of bebop vs. Dixieland. Paul recalls hearing a Charlie Parker record in ’48 or ’49. “I didn’t really know what was happening, but it sounded good to me. It sounded different – interesting and exciting. And I heard Symphony Sid’s radio program from Birdland, sent away for 78 rpm records with Max Roach, Bud Powell. I still didn’t know about the construction of music, but it had me, it grabbed me. I remember driving down to New York one time: the smoke-filled rooms – I was 16 or so – Birdland was packed, went across the street and saw Dizzy Gillespie with his big band opposite George Shearing’s quintet with Denzil Best. It was great.

“I went into the Navy because the Korean War was happening, and I found out if you joined the Navy you could go to music school in Washington, D.C. I missed out on the school because I got sick, and when I got out of the hospital they shipped me out, so I spent a couple of years going back and forth from the Mediterranean – but playin’ in the band. And coming out, I stayed in New York. I was in Brooklyn. That’s the start of my professional playing. I was already 24 or 25.

“There used to be a lot of sessions in New York,” Motian continues. “There were chances to play. At the Open Door, near where NYU is now, they had sessions during the week and on the weekend Monk or Bird. One night Arthur Taylor didn’t show up and Bob Reisner, who was running the sessions, said, ‘Go get your drums, you can play with Thelonious. I ran home, got the drums, ran back, played with Thelonious, and he gave me $10 at the end of the night. I was the happiest guy in the world. Fantastic.

“In those days I was out every night looking for places to play, and I found them. I met Bill Evans right around that time, out on an audition for Jerry Wald – he had a big band for a while, and then a sextet – I found about at the musicians union. Bill was also auditioning. We hit it off right away, both got the gig and went on the road. Then Bill and I hooked up with Tony Scott and hooked up with Don Elliott. We did some records with him – and with Jimmy Knepper, Milt Hinton, Henry Grimes, Sahib Shihab. There’s one of me and Bill and Scott LaFaro playing with Tony Scott that’s never been released. And Lennie Tristano’s record company just put out a second that Henry and I did with Lennie back then.

“I learned so much from all of that, man. I worked a lot with Lennie, actually. One time we played the Half Note for 10 weeks. Think about that today: 10 weeks in the same club? He kept me, but he used a different bass player every week: Paul Chambers, Teddy Kotick, Peter Ind, Jimmy Garrison, Henry Grimes, Whitey Mitchell, Red Mitchell. They all played differently, of course, but I loved all those people, and I never thought about making any adjustments for any of them. I just played what was happening.

“So Bill and I stayed close. We used to play every day in his place, which was tiny. This is before his first record, before he played with Miles. We’d play tunes, or he’d write a tune. I told you about my first record; I think the second one was either Bill’s trio, New Conception, or a George Russell record where we played “All About Rosie.” Yeah, that: I think Bill’s trio with Kotick was the third record I did. I listen to some of those records now, and I’m really proud to have been part of them.

“I saw someone the other day who I recognized from years ago, I don’t know his name, and he said, ‘Oh, yeah, I remember you – you were the house drummer at Birdland.’ I didn’t remember it like that. I worked some gigs there. But when he said that, I realized I played there a lot. With Bill Evans opposite Basie – what a night that was – oh, man! I played there with Mose Allison, with Oscar Pettiford, with Chris Connor, with Zoot Sims, with Sonny Rollins once. I got to play with Coltrane in there, because Elvin was late. In those days Pee Wee Marquette, the doorman, used to say, ‘We don’t want no lulls between the bands – no lulls, no lulls.’ Elvin’s late, Pee Wee says ‘Paul, will you play with John?’ ‘Oh no, I can’t, I don’t want to play with John.’ They talked me into it. That was a real challenge. I remember thinking, ‘I don’t want to sound like Elvin.’ And he was so strong, his presence was so strong, it was hard not to sound like that.”

Did Motian sit down and try to determine what he did want to play to make himself distinctive and original? Or did he just sit and play it?

“Yeah, just played,” he recalls. “At times it seemed hard. I had a hard time getting with Scott LaFaro at the very beginning,

’cause I wasn’t used to the way he played – they said in those days, ‘This guy sounds like a guitar player.’ We didn’t click right away, it wasn’t like, ‘Ah, magic!’ Personally we were good friends; remember, he hadn’t been playing that long either, just a couple years at that point. It took a little time, but we hooked up, hooked up good. We each made adjustments, maybe, but we didn’t talk about it. We didn’t even rehearse much. Playin’, okay, but rehearsals, no.”

Hearing the Evans trio’s records today, one may become aware of their narrative detail – what subtly nuanced stories those three told – and the reorganization of the piano trio into a more equal unit.

“We knew we were doing something that was different, new, good and valid,” Motian testifies. “It was like three people being one voice instead of a piano with bass and drums accompaniment. We talked about that. And at the end of our Vanguard gig, when we recorded, we were talking about how we really reached a peak, we’ve got to be sure we work more, play more. But Scott died that Fourth of July weekend, the same year. Bill stopped playing for a while. I took some other gigs. Around the same time things started changing in New York. Albert Ayler was here, Paul Bley, the Jazz Composers Guild started – I wanted to be part of that. And stuff with Bill seemed at a standstill. We were doing the same stuff over and over. I quit Bill in California, when we were on the road.

“I’ll never forgive myself for that, but at the same time I couldn’t make it anymore. We were at Shelly Manne’s club, with Chuck Israels. The first night was great. The second night was a little not so great, and the third night. . . Everyone was telling me I was too loud, so I played softer and softer until I felt like I wasn’t even playing. I got pissed off and I quit. Bill said, ‘Please, don’t do this. ‘ But I paid my own way back to New York. What a horrible thing to do. If anyone ever did that to me now. . . Anyway, in New Ork I got back into the scene. I was in a band in the Village with Paul Bley, John Gilmore, Albert Ayler and Gary Peacock. We make two, five dollars a night.”

Didn’t time explode in the mid ’60s? Sure, but Motian simply kept his fingers on the intangible pulse. As he explains his method now, “I’m discovering the music as I do it. Playing a couple of nights ago, in Frankfort, with Dewey, Charlie Haden and Baikida Carroll, I did some technical things on the drum set I’d never done before, and I realized it at the moment or just after. The discovery as you do it, that’s what turns me on. I don’t know what I’m going to do when I go out there, nothing is pre-planned. I’m hoping I’m going to turn myself on, and that’s going to turn the drum solo or playing on, and it’s going to turn itself on and make me do something even better, make me grow.

“You ask about my characteristics. Well, I would say I have a sound. I do have sound that’s me, that’s my sound, and 90 percent of the time I can get that sound on any drum set. It’s the tuning, and I don’t have any preset about it, I’m just using my ears. Each drum has a different tonality, and I use my ears to get that which is pleasing to me and my ears. That’s my sound – plus the cymbal I’ve been playing on for 30 years or so.”

Keith Jarrett was the next leader to benefit from Motian’s sound, from his first LP as a trio leader (Life Between the Exit Signs, with Haden, too) to his last with a quintet (Mysteries, with Redman, Haden and Guilhermo Franco),

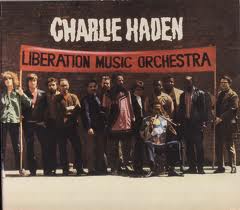

including such highlights as The Survivor’s Suite (quartet as above, without Franco). Though Paul did night club work for bread during the lean rock-impact years (“A waiter at the Vanguard asked me one night, ‘Paul, would you work with the Beatles?’ and I said, ‘Hell no, are you kidding me, man?'”), he didn’t exactly suffer. Due to a connection with Alan Arkin’s bass-playing brother Bob, Motian backed Arlo Guthrie at Woodstock and on the road, alternating weekends between the folky and Jarrett’s associate Charles Lloyd. These were literally riotous times, which were captured by Charlie Haden’s Liberation Music Orchestra. There, under a red and black banner held by Haden and arranger Carla Bley, stands Paul between clarinetist Perry Robinson and trombonist Roswell Rudd, among Gato Barbieri, Don Cherry, Mike Mantler, Bob Northern, Howard Johnson, Andrew Cyrille and guitarist Sam Brown.

Motian knows just where he waws on the nights Bobby Kennedy was murdered and Martin Luther King, Jr., was shot dead, during the Chicago Democratic convention of ’68 and other calamitous events. (Besides having sharp recall, he’s kept a detailed gig log from an early point in

“But as far as the political thing goes, I don’t consider myself knowledgeable enough. I’m into the music. The politics were Charlie’s stuff; I don’t say I don’t agree with it, ’cause I’m more on his side than any other.” Maybe Motian just happened to be around to cut “For a Free Portugal” for Haden’s Closeness album of duets, but titles such as “American Indian: Song of Sitting Bull,” “Inspiration from a Vietnamese Lullaby” and versons of Ornette Coleman’s “War Orphans” and Haden’s “Song for Che” on Motian’s own early ECM recordings suggests his political consciousness was no source of shame.

Working with Jarrett – “That sort of disintegrated; it was inevitable we would break up” – Motian had met Manfred Eicher and Thomas Stowsand (who became his European agent) of ECM. “On our first Europe tour, they were like roadies,” he says. His sound must have appealed to Eicher; certainly Motian’s brush work, his crisp stick patterns and his emphasis on the higher surfaces (rather than the bass drum) of the traps has been well served by ECM’s studio and engineers. “ECM offered me a record. I was still with Keith, but I was writing, My first record, Conception Vessel, had different people playing different things: Keith for one track, a trio with Sam Brown and Charlie, another track with [violinist] Leroy Jenkins, Charlie and [flutist] Becky Friend.

“Then Sam Brown told me about another guitarist, Paul Metzke, whom he liked; why didn’t we try something with two guitars? I thought it was a good idea, I wanted to do that, that was Tribute. By then Keith’s thing was over; the Tin Palace on the Bowery was happening, there were a lot of new people I hadn’t heard around and I didn’t know who I wanted, so I started going out, listening. I heard people I liked and talked to them; some were willing, some weren’t. I liked (saxophonist] Charles Brackeen, his playing, so we got together, and [bassist] David Izenzon – I’d known him for years. I got into putting together my own stuff; our album’s called Dance. Le Voyage was my next trio record, with Brackeen and [bassist] J.F. Jenny-Clark. I had Arild Anderson play bass on one tour. Then in 1980, summer, somehow it wasn’t working anymore. I want to changre, get out of that bass/saxophone/drum format. I wanted guitars. I played a gig with Pat Metheny and he recommended Bill Frisell. We’ve been together almost five years now, and the rest of the band came by people suggersting other people.

“I think Tim Berne brought up Ed Schuller’s name – if we play a tune with changes, Eddie’s cool, and if we play free, he’s cool: he can cover. Marc Johnson [bassist], I think, recommended Joe Lovano, and after I got with him, I wanted another one (tenor saxophonist]. Mack Goldsbury did one French tour with me – he’s from Texas and had that sound, but it didn’t quite work out. Then I found Jim Pepper, and we’ve been doing that.

“I also had in the back of my mind this thing about the saxophone and guitar and drums, without a bass. I never had the nerve to pull it off or try it. Then I did try it, and I liked it, it worked out. Now I’m working mostly with the trio, but the quintet’s still together when there’s money and interest in it. But it’s so simple with the trio, the transportation aspect, the money. I don’t even carry drums. The three of us can fit in one cab.”

This may sound like Motian’s typical flexibility and practicality, but he’s got a new attitude about his career, now accepting the drums – and his urge to compose – and laughing about at least some of the dues paying that attends most jazz endeavors. “I found out it’s possible to do your own and other stuff. You don’t have to be exclusive. Like, I’m playing with [pianist] Marilyn Crispell at Carnegie Recital Hall – she was up here rehearsing yesterday; that’s going to be nice. Or this thing with Charlie, Dewey and Baikida, and I’m going to Canada for a couple of weeks with David Friesen. In the past, when people called, I wouldn’t take their gigs, because everything I did took me away from my stuff, and it took me too long to get back into it, writing tunes, playing and rehearsing. But I’ve changed. I just made a record for ECM with Paul Bley, John Surman and Bill Frisetll. First time I’ve played with Bley in 20 years.

“I like melody, lyrics, tunes and songs more and more,” Motian admits. “Writing is not easy for me. I’ll have an idea, or sit at a piano – I’m a terrible pianist – and play until I do something I like, then write that down and keep it in mind. It’s not easy for me because I’m not knowledgeable, but I trust my ears and my intuition, and that’s the right way.

“That’s something I learned on piano, that taught me something about drums. I was taking piano lessons, playing a piece of music, looking down at my hands and I was really playing the piece. I remember thinking, ‘Whose hands are those? They can’t be mine.’ That’s great when that happens; you trust yourself. You know, you’re playing with someone and you’re thinking, ‘I should change the tempo now, I should anticipate. . . ‘ Or you’re playing a tune and it’s ending and you think, ‘Okay, I should end this now . . .’ No, it’s cool, just sit back and trust yourself. When the right time for that to happen is happening you’ll know it and you’ll just do it. Wait, trust yourself, it will end when the time comes. Now I do that, I trust myself.”

Of course he does. His past prove that many others have, and his present attests to his success.