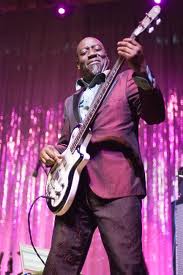

Jamaaladeen Tacuma, free-funk electric bass virtuoso, protege of Ornette Coleman and one of the dancingest musicians on the planet, has been named one of 12 Philadelphia artists receiving $60,000 fellowships from the Pew Center for Arts and Heritage. Two other musicians are also 2011 Pew fellows: electronic music improviser Charles Cohen and exploratory folk/rock/goth guitarist Chris Forsyth.

The Pew’s level of financial support is comparable to the Herb Alpert Award ($75k) though not as much as the MacArthur Fellows Program ($500k over five years), more than a Guggenheim Fellowship (reportedly averaging around $43k in 2008) and more than the National Endowment for the Art’s Jazz Masters each receive as lifetime achievement prizes ($25k).

While Alperts, MacArthurs, Guggenheims and foreign prizes such as Denmark’s JazzPar (discontinued in 1984) have in recent years been bestowed on assertively experimental, innovative and avant-garde improvisers — and Tacuma can stand as an equal among them — he is still a surprising grant recipient. On the face of things, a 55-year-old electric bassist with the verve to get people on their feet might seem too “pop” for foundation money. However, Forsyth and Cohen are uncommon award winners, too. Pew fellows do not apply but are selected through a nomination process.

Tacuma’s latest album demonstrates the breadth and depth of his interests: For The Love of Ornette is self-produced, only available through the artist’s own means of distribution and fun to listen to, dramatic and varied, but far from the formulas of pop music. Ornette is (of course) Ornette Coleman, the internationally acclaimed American iconoclast, mentor/inspiration to Tacuma (among legions of others), subject of a suite on the album and featured throughout the album playing alto saxophone. He is the very prophet of “free jazz.”

“Fellas, can you hear me?” Coleman says to Tacuma’s ensemble of seven, opening the title track of Tacuma’s album. “Forget the note and get to the idea.” That’s a characteristic dictum of the “harmolodic” world-view Coleman has pro-offered and Tacuma has practiced some 35 years, since the relentless “freely” improvised electronic funk rave-up Dancing In Your Head, released in 1977. There are other worthy contributors to For the Love of. . . including Tony Kofi on tenor saxophone, Wolfgang Puschnig on flute and the double-reed hojak, and Yoichi Uzeki playing piano, Coleman’s concept dominates this album.

What “free” means in this context is that music isn’t ruled by rules — categories, conventions, constraints — but is foremost an expression an individual’s personal views and truths, in conjunction, usually, with other individuals’ equally unique statements. Furthermore: All those individuals (participatory listeners included) can come together through collective improvisation.

Jamaaladeen Tacuma talks about himself

The logical basis of harmolodics is often doubted by musicians trained in Western classical style, though its precepts as articulated by Coleman uncover zen-like wisdom in allusion and contradiction, and would appear to be applicable across many performing arts. Tacuma may have an inherent inclination to realize harmony, melody and motion as inseparable elements of lively musical self-expression — Coleman took him as a harmolodic natural when they first met, and relied upon him for his electrically-infused projects from 1976 through ’87. They have not recorded together for 24 years.

In the ’80s Jamaaladeen released several albums of his own with infectious rhythms, hot licks and classical accents from winds and string sections. Readers of my book Miles Ornette Cecil – Jazz Beyond Jazz and articles over the years (even before I was managing-edited Guitar World, 1982 – 83) know of my enthusiasm for Tacuma’s bass playing and upbeat, direct immediacy. He’s one of those rare and valuable people who bring bounce to life, apparently possessed with bold, joyous engagement. He seems to have been overlooked by the jazz press and public over the past decade (perhaps because he lives in Philadelphia, heading his large family). If so, it’s the press’s fault — he’s been busy, popular at festivals in Europe, recording with an array of collaborators ranging from phenomenological atonalist Derek Bailey to black rockateer Vernon Reid, opera singer Wilhelmina Fernandez to Belgian Arabic hip-hop stylist Natacha Atlas.

Tacuma’s foundational, rubbery, striding sounds give a lift to almost every situation, and he puts himself into some odd ones, seldom sounding predictable, never dull. Here’s hoping the Pew Award gives him a bit of financial security and an extra infusion of energy he’ll pass on to the rest of us.